Amygdalin

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.045.372 |

| MeSH | Amygdalin |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C20H27NO11 | |

| Molar mass | 457.429 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

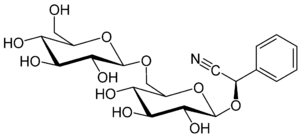

Amygdalin (from Greek: ἀμυγδάλη amygdálē “almond”), C20H27NO11, is a glycoside initially isolated from the seeds of the tree Prunus dulcis, also known as bitter almonds, by Pierre-Jean Robiquet[1] and A. F. Boutron-Charlard in 1803, and subsequently investigated by Liebig and Wöhler in 1830, and others. Several other related species in the genus of Prunus, including apricot (Prunus armeniaca) and black cherry (Prunus serotina),[2] also contain amygdalin. It was promoted as a cancer cure by Ernst T. Krebs under the name "Vitamin B17", but studies have found it to be ineffective.[3][4][5]

Chemistry

Amygdalin is extracted from almond or apricot kernel cake by boiling ethanol; on evaporation of the solution and the addition of diethyl ether, amygdalin is precipitated as white minute crystals. Liebig and Wöhler were already able to find three decomposition products of the newly discovered amygdalin: sugar, benzaldehyde, and prussic acid.[6] Later research showed that sulfuric acid decomposes it into d-glucose, benzaldehyde, and prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide); while hydrochloric acid gives mandelic acid, d-glucose, and ammonia.[7]

The decomposition induced by enzymes may occur in two ways. Maltase partially decomposes it, giving d-glucose and mandelic nitrile glucoside, C6H5CH(CN)O·C6H11O5; this compound is isomeric with sambunigrin, a glucoside found by E.E. Bourquelot and Danjou in the berries of the Common Elder, Sambucus nigra. Emulsin, on the other hand, decomposes it into benzaldehyde, cyanide, and two molecules of glucose; this enzyme occurs in the bitter almond, and consequently the seeds invariably contain free cyanide and benzaldehyde. An "amorphous amygdalin" is said to occur in the cherry-laurel. Closely related to these glucosides is dhurrin, C14H17O7N, isolated by W. Dunstan and T. A. Henry from the common sorghum or "great millet," Sorghum vulgare; this substance is decomposed by emulsin or hydrochloric acid into d-glucose, cyanide, and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde.[citation needed]

Natural amygdalin has the R configuration at the chiral benzyl center. Under mild basic conditions, this stereogenic center epimerizes; the S epimer is called neoamygdalin.[8]

Laetrile

Amygdalin is sometimes confounded with laevomandelonitrile, also called laetrile for short; however, amygdalin and laetrile are different chemical compounds.[8] Laetrile, which was patented in the United States, is a semi-synthetic molecule sharing part of the amygdalin structure, while the "laetrile" made in Mexico is usually amygdalin, the natural product obtained from crushed apricot pits, or neoamygdalin.[9]

Though it is sometimes sold as "Vitamin B17", it is not a vitamin. Amygdalin/laetrile was claimed to be a vitamin by Ernst Krebs, Jr in the hope that if classified as a nutritional supplement it would escape the federal legislation regarding the marketing of drugs. He could also capitalise on the public fad for vitamins at that time.[10]

Toxicity

Beta-glucosidase, one of the enzymes that catalyzes the release of the cyanide from amygdalin, is present in human small intestine and in a variety of common foods. This leads to an unpredictable and potentially lethal toxicity when amygdalin or Laetrile is taken orally.[10][11]

Cancer treatment

A 2006 Cochrane review of the evidence concluded "The claim that Laetrile has beneficial effects for cancer patients is not supported by data from controlled clinical trials. This systematic review has clearly identified the need for randomised or controlled clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of Laetrile or amygdalin for cancer treatment."[12] It has not been approved for this use by the United States' Food and Drug Administration.[9] The U.S. government's National Institutes of Health evaluated the evidence, including case reports and a clinical trial, and concluded that they showed little effect.[13] A 1982 trial of 178 patients found that tumor size had increased in all patients. Minimal side effects were seen except in two patients who consumed bitter almonds and suffered from cyanide poisoning.[14]

A study in 2006 on the treatment of prostate cancer concluded: "Based on these results, amygdalin shows considerable promise in the treatment of prostate cancer."[15]

In 1974, the American Cancer Society officially labelled laetrile as quackery, but advocates for laetrile dispute this label, asserting that financial motivations have tainted the published research.[16] Some North American cancer patients have travelled to Mexico for treatment with the substance, allegedly under the auspices of Dr. Ernesto Contreras.[17] One of these patients was actor Steve McQueen, who died in Mexico following surgery to remove a stomach tumour while undergoing treatment for mesothelioma.[18] Laetrile advocates within the United States include the late Dean Burk Ph.D.,[19] a former chief chemist of the National Cancer Institute's cytochemistry laboratory[20] and national arm wrestling champion Jason Vale, who claimed that his kidney, pancreatic, and spleen cancer were cured by eating apricot seeds. Vale was convicted in 2003 for, among other things, marketing laetrile.[21] The US Food and Drug Administration continues to seek jail sentences for vendors selling laetrile for cancer treatment, calling it a "highly toxic product that has not shown any effect on treating cancer."[22]

Amygdalin was first isolated in 1830. In 1845 it was used for cancer in Russia, and again in the 1920s in the United States, but it was considered too poisonous.[13] In the 1950s a reportedly nontoxic, synthetic form was patented for use as a meat preservative,[23] and later marketed as Laetrile for cancer treatment.[13] In 1972, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center board member Benno Schmidt convinced the hospital to test laetrile so that he could assure others of its ineffectiveness "with some conviction".[24] However, the respected scientist put in charge of the testing, Kanematsu Sugiura, found that laetrile inhibited the secondary tumors in mice without destroying the primary tumors. He repeated the experiment three times with the same results, and then three more times. In a blinded test, however, he was unable to conclude that laetrile had anticancer activity. His first three experiments were not published because, in the words of Chester Stock, Sugiura's supervisor, "it would have caused all kind of havoc". Nevertheless the results were leaked in 1973, causing a stir. Subsequently laetrile was tested on 14 tumor systems, and a Sloan-Kettering press release concluded that "laetrile showed no beneficial effects".[24] Three other researchers were unable to confirm Sugiura's results, although one of three did confirm Sugiara's results in one of his three studies. Mistakes in the Sloan-Kettering press release were highlighted by a group of laetrile proponents led by Ralph Moss, former public affairs official of Sloan-Kettering hospital, who was fired when he announced his membership in the group. These mistakes were considered inconsequential, but Nicholas Wade in Science noted that "even the appearance of a departure from strict objectivity is unfortunate."[24] The results from these studies were published all together.[25]

See also

- United States v. Rutherford, 442 U.S. 544 (1979). Finding: The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act makes no express exception for drugs used by the terminally ill and no implied exemption is necessary to attain congressional objectives or to avert an unreasonable reading of the terms "safe" and "effective" in 201 (p) (1).

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- ^ "A chronology of significant historical developments in the biological sciences". Botany Online Internet Hypertextbook. University of Hamburg, Department of Biology. 2002-08-18. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Swain E, Poulton JE (1994). "Utilization of Amygdalin during Seedling Development of Prunus serotina". Plant physiology. 106 (2): 437–445. PMC 159548. PMID 12232341.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ellison, N (1978). "Special report on Laetrile: the NCI Laetrile Review. Results of the National Cancer Institute's retrospective Laetrile analysis". New England Journal of Medicine. 299 (10): 549–52. PMID 683212.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moetel, CG (1981). "A pharmacologic and toxicological study of amygdalin". Journal of the American Medical Association. 245 (6): 591–4. doi:10.1001/jama.245.6.591.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moertel, CG (1982). "A clinical trial of amygdalin (Laetrile) in the treatment of human cancer". New England Journal of Medicine. 306 (4): 201–6. PMID 7033783.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ F. Wöhler, J. Liebig (1837). "Ueber die Bildung des Bittermandelöls". Annalen der Pharmacie. 22 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1002/jlac.18370220102.

- ^ J. W. Walker, V. K. Krieble (1909). "The hydrolysis of amygdalin by acids. Part I". Journal of the Chemical Society. 95 (11): 1369–1377. doi:10.1039/CT9099501369.

- ^ a b Fenselau C, Pallante S, Batzinger RP; et al. (1977). "Mandelonitrile beta-glucuronide: synthesis and characterization". Science (journal). 198 (4317): 625–7. doi:10.1126/science.335509. PMID 335509.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b What is laetrile?, National Cancer Institute, Retrieved on 14 January 2007

- ^ a b Laetrile: A Lesson in Cancer Quackery Ca Cancer J Clin 1981;31;91-95

- ^ Amygdalin (Laetrile) and prunasin beta-glucosidases: distribution in germ-free rat and in human tumor tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 October; 78(10): 6513–6516.

- ^ Milazzo S, Ernst E, Lejeune S, Schmidt K (2006). "Laetrile treatment for cancer". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005476.pub2. PMID 16625640.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Laetrile/Amygdalin - National Cancer Institute<

- ^ Moertel, C.G., (1982). "A clinical trial of amygdalin (laetrile) in the treatment of human cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 15 (306): 201–206. doi:10.1007/s00520-006-0168-9. PMID 7033783.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chang, et al. Amygdalin induces apoptosis through regulation of Bax and Bcl-2 expressions in human DU145 and LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29(8) 1597—1602 (2006)).

- ^ Day, Phillip: Cancer: why we're still dying to know the truth, Credence Publications, Tonbridge, 1999, p. 43

- ^ Moss RW (2005). "Patient perspectives: Tijuana cancer clinics in the post-NAFTA era". Integr Cancer Ther. 4 (1): 65–86. doi:10.1177/1534735404273918. PMID 15695477.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "McQueen's Legacy of Laetrile". New York Times. 2005-11-15.

- ^ Dr Dean Burk, The Moss Reports

- ^ Dean Burk, 84, Noted Chemist At National Cancer Institute, Dies, Washington Post, 9 October 1988

- ^ McWilliams, Brian, The Spam Kings, O'Reilly, 2005 ISBN 0596007329

- ^ US FDA (June 22, 2004). Lengthy Jail Sentence for Vendor of Laetrile—A Quack Medication to Treat Cancer Patients. FDA News

- ^ Hexuronic acid derivatives

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|country-code=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor2-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor2-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|issue-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|patent-number=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Wade N (1977). "Laetrile at Sloan-Kettering: A Question of Ambiguity". Science (journal). 198 (4323): 1231–1234. doi:10.1126/science.198.4323.1231. PMID 17741690.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Published in Journal of Surgical Oncology 10(2). Link.