Gliese 876

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Aquarius |

| Right ascension | 22h 53m 16.7s |

| Declination | −14° 15′ 49″ |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 10.18 |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | M3.5V |

| U−B color index | 1.15 |

| B−V color index | 1.59 |

| R−I color index | 1.22 |

| Variable type | BY Draconis |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | -1.7 ± 2 km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 960.33 ± 3.77 mas/yr Dec.: -675.64 ± 1.58 mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 212.59 ± 1.96 mas |

| Distance | 15.3 ± 0.1 ly (4.70 ± 0.04 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 11.82 |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.32 ± 0.03 M☉ |

| Radius | 0.36 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.0124 L☉ |

| Temperature | 3,480 ± 50 K |

| Metallicity | 75% solar |

| Rotation | 96.7 days |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 0,019362 km/s |

| Age | 9.9 × 109 years |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| ARICNS | data |

| Data sources: | |

| Hipparcos Catalogue, CCDM (2002), Bright Star Catalogue (5th rev. ed.) | |

Gliese 876, also catalogued as IL Aquarii, is a red dwarf star approximately 15 light-years away from Earth in the constellation of Aquarius (the Water-bearer). As of 2008, it has been confirmed that three extrasolar planets orbit the star. Two of the planets are similar to Jupiter, while the closest planet is thought to be similar to a small Neptune or a large Earth.

Distance and visibility

Gliese 876 is located fairly close to our solar system. According to astrometric measurements made by the Hipparcos satellite, the star shows a parallax of 212.59 milliarcseconds,[1] which corresponds to a distance of 4.70 parsecs (15.3 light years). Despite being located so close to Earth, the star is so faint that it is invisible to the naked eye and can only be seen using a telescope.

Stellar characteristics

As a red dwarf star, Gliese 876 is much less massive than our Sun: estimates suggest it has only 32% of the mass of our local star.[2] The surface temperature of Gliese 876 is cooler than our Sun and the star has a smaller radius.[3] These factors combine to make the star only 1.24% as luminous as the Sun, though most of this is at infrared wavelengths.

Estimating the age and metallicity of cool stars is difficult due to the formation of diatomic molecules in their atmospheres, which makes the spectrum extremely complex. By fitting the observed spectrum to model spectra, it is estimated that Gliese 876 has a slightly lower abundance of heavy elements compared to the Sun (around 75% the solar abundance of iron).[4] Based on chromospheric activity the star is likely to be around 6.52 or 9.9 billion years old, depending on the theoretical model used.[5]

Like many low-mass stars, Gliese 876 is a variable star. It is classified as a BY Draconis variable and its brightness fluctuates by around 0.04 magnitudes.[6] This type of variability is thought to be caused by large starspots moving in and out of view as the star rotates.[7]

Planetary system

On June 23, 1998, an extrasolar planet was announced in orbit around Gliese 876 by two independent teams led by Geoffrey Marcy[2] and Xavier Delfosse.[8] The planet was designated Gliese 876 b and was detected by making measurements of the star's radial velocity as the planet's gravity pulled it around. The planet, around twice the mass of Jupiter, revolves around its star in an orbit taking approximately 61 days to complete, at a distance of only 0.208 AU, less than the distance from the Sun to Mercury.[9]

On April 4, 2001, a second planet was detected in the system, inside the orbit of the previously-discovered planet.[10] The 0.62 Jupiter-mass planet, designated Gliese 876 c is in a 1:2 orbital resonance with the outer planet, taking 30.340 days to orbit the star. This relationship between the orbital periods initially disguised the planet's radial velocity signature as an increased orbital eccentricity of the outer planet. Eugenio Rivera and J. Lissauer found that the two planets undergo strong gravitational interactions as they orbit the star, causing the orbital elements to change rapidly.[11]

Both of the system's Jupiter-mass planets are located in the 'traditional' habitable zone (HZ) of Gliese 876, which extends between 0.116 to 0.227 AU from the star.[12] This leaves little room for an additional habitable Earth-size planet in that part of the system. On the other hand, large moons of the gas giants, if they exist, may be able to support life. Furthermore, the habitable zone for planets whose rotation is synchronous with their orbital motion may be wider than the traditional view, which may enable the existence of habitable planets elsewhere in the system.[13]

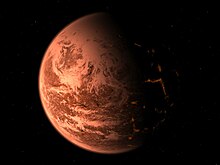

On June 13, 2005, further observations by a team led by Rivera revealed a third planet in the system, inside the orbits of the two Jupiter-size planets.[14] The planet, designated Gliese 876 d, has a minimum mass only 5.88 times that of the Earth and may be a terrestrial planet. Based on the radial velocity measurements and modelling the interactions between the two giant planets, the system's inclination is estimated to be around 50° to the plane of the sky. If this is the case and the system is assumed to be coplanar, the planetary masses are around 30% greater than the lower limits established by the radial velocity method. This would make the inner planet have a true mass around 7.5 times that of Earth. On the other hand, astrometric methods suggest an inclination around 84° for the outermost planet, which would mean the true masses are only slightly greater than the lower limit..[15] Another investigation led by Paul Shankland (which included Rivera and others), reveals a lack of any astronomical transits of the planets across the face of the star -- along with a radial velocity 'tilt' away from 90° (caused by the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect) -- and so indicates the notional ~90° inclination is further unlikely.[16] Rivera's team suggests a possible fourth planet in this system orbiting beyond 0.5 AU in another resonant orbit.[14]

In 2008, the system was used as a test case for the migration of 5 Earth-mass planets which had formed inside the orbit of the innermost gas giant of the system. If it formed at (in this test) 0.07 AU from the star, b's gravity would have pulled d into an eccentric orbit. That orbit then would have restabilised to its current location.[17]

On January 20, 2009, the mutual inclination between planets b and c was determined to be 5.0+3.9

−2.3° from studying planet-planet interactions. It is the first planetary system around a normal star to have mutual inclination between planets determined. Assuming the planetary system is coplanar, it indicated that these planets were formed from the circumstellar disk.[18]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | >0.0185 ± 0.0031 MJ | 0.0208 ± 0.0012 | 1.937760 ± 0.000070 | 0 | — | — |

| c | >0.619 ± 0.088 MJ | 0.1303 ± 0.0075 | 30.340 ± 0.013 | 0.2243 ± 0.0013 | — | — |

| b | >1.93 ± 0.27 MJ | 0.208 ± 0.012 | 60.940 ± 0.013 | 0.0249 ± 0.0026 | — | — |

See also

- Gliese 581

- HD 82943

- List of nearest stars

- List of stars with confirmed extrasolar planets

- Planetary system

- Upsilon Andromedae

- Wilhelm Gliese

References

- ^ "HIP 113020". The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues. ESA. 1997. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ a b Marcy, G.; et al. (1998). "A Planetary Companion to a Nearby M4 Dwarf, Gliese 876". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 505 (2): L147–L149. doi:10.1086/311623.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Johnson, H., Wright, C. (1983). "Predicted infrared brightness of stars within 25 parsecs of the sun". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 53: 643–711. doi:10.1086/190905.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bean, J.L.; et al. (2006). "Metallicities of M Dwarf Planet Hosts from Spectral Synthesis". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 653: L65–L68. doi:10.1086/510527.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Saffe, C.; et al. (2005). "On the Ages of Exoplanet Host Stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 443 (2): 609–626. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053452.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Samus; et al. (2004). "IL Aqr". Combined General Catalogue of Variable Stars. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Bopp, B., Evans, D. (1973). "The spotted flare stars BY Dra, CC Eri: a model for the spots, some astrophysical implications". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 164: 343–356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Delfosse, X.; et al. (1998). "The closest extrasolar planet. A giant planet around the M4 dwarf GL 876". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 338: L67–L70.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Butler, R.; et al. (2006). "Catalog of Nearby Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal. 646: 505–522. doi:10.1086/504701.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) (web version) - ^ Marcy, G.; et al. (2001). "A Pair of Resonant Planets Orbiting GJ 876". The Astrophysical Journal. 556 (1): 296–301. doi:10.1086/321552.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Rivera, E., Lissauer, J. (2001). "Dynamical Models of the Resonant Pair of Planets Orbiting the Star GJ 876" (abstract). The Astrophysical Journal. 558 (1): 392–402. doi:10.1086/322477.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones, B.; et al. (2005). "Prospects for Habitable "Earths" in Known Exoplanetary Systems". The Astrophysical Journal. 622 (2): 1091–1101. doi:10.1086/428108.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Joshi, M.M.; et al. (1997). "Simulations of the Atmospheres of Synchronously Rotating Terrestrial Planets Orbiting M Dwarfs: Conditions for Atmospheric Collapse and the Implications for Habitability". Icarus. 129 (2): 450–465. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5793.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Rivera, E.; et al. (2005). "A ~7.5 M⊕ Planet Orbiting the Nearby Star, GJ 876". The Astrophysical Journal. 634 (1): 625–640. doi:10.1086/491669.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Benedict, G.; et al. (2002). "A mass for the extrasolar planet Gliese 876b determined from Hubble Space Telescope fine guidance sensor 3 astrometry and high-precision radial velocities". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 581 (2): L115–L118. doi:10.1086/346073.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Shankland, P. D.; et al. (2006). "On the Search for Transits of the Planets Orbiting Gliese 876". The Astrophysical Journal. 653 (1): 700–707. doi:10.1086/508562.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Ji-Lin Zhou, Douglas N.C. Lin (2008). "Migration and Final Location of Hot Super Earths in the Presence of Gas Giants". arXiv:0802.0062v1 [astro-ph].

- ^ Bean; et al. (2009). "The architecture of the GJ876 planetary system. Masses and orbital coplanarity for planets b and c". arXiv:0901.3144.

{{cite arXiv}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|journal=ignored (help)

- GJ 876 Catalog

External links

- "Artist renderings and data for the three planets orbiting GJ 876". Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "A Dangerous Sunrise on Gliese 876d". NASA. Astronomy Picture of the Day. 2008-05-21. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "A planet for Gliese 876". NASA. Astronomy Picture of the Day. 1998-06-26. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Gliese 876". Extrasolar Visions. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Gliese 876 / Ross 780". SolStation. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Gliese 876 : THE CLOSEST EXTRASOLAR PLANET". Observatoire de Haute Provence. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Notes for star Gliese 876". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Smallest extrasolar planet found". BBC News. 2005-06-13. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- Image Gliese 876

- Extrasolar Planet Interactions by Rory Barnes & Richard Greenberg, Lunar and Planetary Lab, University of Arizona

- Sky map