Bell test

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

The Bell test experiments serve to investigate the validity of the entanglement effect in quantum mechanics by using some kind of Bell inequality. John Bell published the first inequality of this kind in his paper "On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox". Bell's Theorem states that a Bell inequality must be obeyed under any local hidden variable theory but can in certain circumstances be violated under quantum mechanics. The term "Bell inequality" can mean any one of a number of inequalities — in practice, in real experiments, the CHSH or CH74 inequality, not the original one derived by John Bell. It places restrictions on the statistical results of experiments on sets of particles that have taken part in an interaction and then separated. A Bell test experiment is one designed to test whether or not the real world obeys a Bell inequality. Such experiments fall into two classes, depending on whether the analysers used have one or two output channels.

Conduct of optical Bell test experiments

In practice most actual experiments have used light, assumed to be emitted in the form of particle-like photons (produced by atomic cascade or spontaneous parametric down conversion), rather than the atoms that Bell originally had in mind. The property of interest is, in the best known experiments, the polarisation direction, though other properties can be used.

A typical CHSH (two-channel) experiment

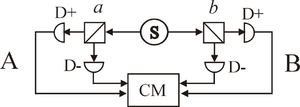

The source S produces pairs of "photons", sent in opposite directions. Each photon encounters a two-channel polariser whose orientation can be set by the experimenter. Emerging signals from each channel are detected and coincidences counted by the coincidence monitor CM.

The diagram shows a typical optical experiment of the two-channel kind for which Alain Aspect set a precedent in 1982 (Aspect, 1982a). Coincidences (simultaneous detections) are recorded, the results being categorised as '++', '+−', '−+' or '−−' and corresponding counts accumulated.

Four separate subexperiments are conducted, corresponding to the four terms E(a, b) in the test statistic S ((2) below). The settings a, a′, b and b′ are generally in practice chosen to be 0, 45°, 22.5° and 67.5° respectively — the "Bell test angles" — these being the ones for which the quantum mechanical formula gives the greatest violation of the inequality.

For each selected value of a and b, the numbers of coincidences in each category (N++, N--, N+- and N-+) are recorded. The experimental estimate for E(a, b) is then calculated as:

(1) E = (N++ + N-- − N+- − N-+)/(N++ + N-- + N+- + N-+).

Once all four E’s have been estimated, an experimental estimate of the test statistic

(2) S = E(a, b) − E(a, b′) + E(a′, b) + E(a′ b′)

can be found. If S is numerically greater than 2 it has infringed the CHSH inequality. The experiment is declared to have supported the QM prediction and ruled out all local hidden variable theories.

A strong assumption has had to be made, however, to justify use of expression (2). It has been assumed that the sample of detected pairs is representative of the pairs emitted by the source. That this assumption may not be true comprises the fair sampling loophole.

The derivation of the inequality is given in the CHSH Bell test page.

A typical CH74 (single-channel) experiment

The source S produces pairs of "photons", sent in opposite directions. Each photon encounters a single channel (e.g. "pile of plates") polariser whose orientation can be set by the experimenter. Emerging signals are detected and coincidences counted by the coincidence monitor CM.

Prior to 1982 all actual Bell tests used "single-channel" polarisers and variations on an inequality designed for this setup. The latter is described in Clauser, Horne, Shimony and Holt's much-cited 1969 article (Clauser, 1969) as being the one suitable for practical use. As with the CHSH test, there are four subexperiments in which each polariser takes one of two possible settings, but in addition there are other subexperiments in which one or other polariser or both are absent. Counts are taken as before and used to estimate the test statistic.

(3) S = (N(a, b) − N(a, b′) + N(a′, b) + N(a′, b′) − N(a′, ∞) − N(∞, b)) / N(∞, ∞),

where the symbol ∞ indicates absence of a polariser.

If S exceeds 0 then the experiment is declared to have infringed Bell's inequality and hence to have "refuted local realism".

The only theoretical assumption (other than Bell's basic ones of the existence of local hidden variables) that has been made in deriving (3) is that when a polariser is inserted the probability of detection of any given photon is never increased: there is "no enhancement". The derivation of this inequality is given in the page on Clauser and Horne's 1974 Bell test.

Experimental assumptions

In addition to the theoretical assumptions made, there are practical ones. There may, for example, be a number of "accidental coincidences" in addition to those of interest. It is assumed that no bias is introduced by subtracting their estimated number before calculating S, but that this is true is not considered by some to be obvious. There may be synchronisation problems — ambiguity in recognising pairs due to the fact that in practice they will not be detected at exactly the same time.

Nevertheless, despite all these deficiencies of the actual experiments, one striking fact emerges: the results are, to a very good approximation, what quantum mechanics predicts. If imperfect experiments give us such excellent overlap with quantum predictions, most working quantum physicists would agree with John Bell in expecting that, when a perfect Bell test is done, the Bell inequalities will still be violated. This attitude has led to the emergence of a new sub-field of physics which is now known as quantum information theory. One of the main achievements of this new branch of physics is showing that violation of Bell's inequalities leads to the possibility of a secure information transfer, which utilizes the so-called quantum cryptography (involving entangled states of pairs of particles).

Notable experiments

Over the past thirty or so years, a great number of Bell test experiments have now been conducted. These experiments have (subject to a few assumptions, considered by most to be reasonable) confirmed quantum theory and shown results that cannot be explained under local hidden variable theories. Advancements in technology have led to significant improvement in efficiencies, as well as a greater variety of methods to test the Bell Theorem.

Some of the best known:

Freedman and Clauser, 1972

- This was the first actual Bell test, using Freedman's inequality, a variant on the CH74 inequality.

Aspect, 1981-2

- Aspect and his team at Orsay, Paris, conducted three Bell tests using calcium cascade sources. The first and last used the CH74 inequality. The second was the first application of the CHSH inequality, the third the famous one (originally suggested by John Bell) in which the choice between the two settings on each side was made during the flight of the photons.

Tittel and the Geneva group, 1998

- The Geneva 1998 Bell test experiments showed that distance did not destroy the "entanglement". Light was sent in fibre optic cables over distances of several kilometers before it was analysed. As with almost all Bell tests since about 1985, a "parametric down-conversion" (PDC) source was used.

Weihs' experiment under "strict Einstein locality" conditions

In 1998 Gregor Weihs and a team at Innsbruck, lead by Anton Zeilinger, conducted an ingenious experiment that closed the "locality" loophole, improving on Aspect's of 1982. The choice of detector was made using a quantum process to ensure that it was random. This test violated the CHSH inequality by over 30 standard deviations, the coincidence curves agreeing with those predicted by quantum theory.

Pan et al.'s experiment on the GHZ state

This is the first of new Bell-type experiments on more than two particles; this one uses the so-called GHZ state of three particles; it is reported in Nature (2000)

Gröblacher et al. (2007) test of Leggett-type non-local realist theories

The authors interpret their results as disfavouring "realism" and hence allow QM to be local but "non-real". However they have actually only ruled out a specific class of non-local theories suggested by Anthony Leggett.[1][2]

Salart et al. (2008) Separation in a Bell Test

This experiment filled a loophole by providing an 18 km separation between detectors, which is sufficient to allow the completion of the quantum state measurements before any information could have traveled between the two detectors.[3][4]

Loopholes

Though the series of increasingly sophisticated Bell test experiments has convinced the physics community in general that local realism is untenable, there are still critics who point out that the outcome of every single experiment done so far that violates a Bell inequality can, at least theoretically, be explained by faults in the experimental setup, experimental procedure or that the equipment used do not behave as well as it is supposed to. These possibilities are known as "loopholes". The most serious loophole is the detection loophole, which means that particles are not always detected in both wings of the experiment. It is possible to "engineer" quantum correlations (the experimental result) by letting detection be dependent on a combination of local hidden variables and detector setting. Experimenters have repeatedly stated that loophole-free tests can be expected in the near future (García-Patrón, 2004). On the other hand, some researchers point out that it is a logical possibility that quantum physics itself prevents a loophole-free test from ever being implemented (Gill, 2003; Santos, 2006).

Notes

- ^ Quantum physics says goodbye to reality

- ^ An experimental test of non-local realism

- ^ Salart, D.; Baas, A.; van Houwelingen, J. A. W.; Gisin, N.; and Zbinden, H. “Spacelike Separation in a Bell Test Assuming Gravitationally Induced Collapses.” Physical Review Letters 100, 220404 (2008).

- ^ http://www.physorg.com/news132830327.html

References

- Aspect, 1981: A. Aspect et al., Experimental Tests of Realistic Local Theories via Bell's Theorem, Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 460 (1981)

- Aspect, 1982a: A. Aspect et al., Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell's Inequalities, Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 91 (1982),

- Aspect, 1982b: A. Aspect et al., Experimental Test of Bell's Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers, Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1804 (1982),

- Barrett, 2002 Quantum Nonlocality, Bell Inequalities and the Memory Loophole: quant-ph/0205016 (2002).

- Bell, 1987: J. S. Bell, Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, (Cambridge University Press 1987)

- Clauser, 1969: J. F. Clauser, M.A. Horne, A. Shimony and R. A. Holt, Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories, Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 880-884 (1969),

- Clauser, 1974: J. F. Clauser and M. A. Horne, Experimental consequences of objective local theories, Phys. Rev. D 10, 526-35 (1974)

- Freedman, 1972: S. J. Freedman and J. F. Clauser, Experimental test of local hidden-variable theories, Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 938 (1972)

- García-Patrón, 2004: R. García-Patrón, J. Fiurácek, N. J. Cerf, J. Wenger, R. Tualle-Brouri, and Ph. Grangier, Proposal for a Loophole-Free Bell Test Using Homodyne Detection, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 130409 (2004)

- Gill, 2003: R.D. Gill, Time, Finite Statistics, and Bell's Fifth Position: quant-ph/0301059, Foundations of Probability and Physics - 2, Vaxjo Univ. Press, 2003, 179-206 (2003)

- Kielpinski: D. Kielpinski et al., Recent Results in Trapped-Ion Quantum Computing (2001)

- Kwiat, 1999: P.G. Kwiat, et al., Ultrabright source of polarization-entangled photons, Physical Review A 60 (2), R773-R776 (1999)

- Rowe, 2001: M. Rowe et al., Experimental violation of a Bell’s inequality with efficient detection, Nature 409, 791 (2001)

- Santos, 2005: E. Santos, Bell's theorem and the experiments: Increasing empirical support to local realism: quant-ph/0410193, Studies In History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 36, 544-565 (2005)

- Tittel, 1997: W. Tittel et al., Experimental demonstration of quantum-correlations over more than 10 kilometers, Phys. Rev. A, 57, 3229 (1997)

- Tittel, 1998: W. Tittel et al., Experimental demonstration of quantum-correlations over more than 10 kilometers, Physical Review A 57, 3229 (1998); Violation of Bell inequalities by photons more than 10 km apart, Physical Review Letters 81, 3563 (1998)

- Weihs, 1998: G. Weihs, et al., Violation of Bell’s inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5039 (1998)