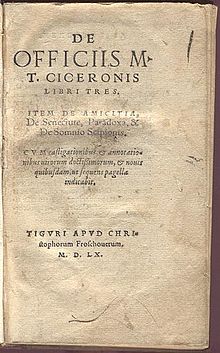

De Officiis

De Officiis (On Duties or On Obligations) is an essay by Marcus Tullius Cicero divided into three books, in which Cicero expounds his conception of the best way to live, behave, and observe moral obligations.

Origin

De Officiis was written in October-November of 44 BC, in under four weeks time.[1] This was Cicero's last year alive, and he was 62 years of age. Cicero was at this time still active in politics, trying to stop revolutionary forces from taking control of the Roman Republic. Despite his efforts, the republican system failed to revive even upon the assassination of Caesar, and Cicero was himself assassinated shortly thereafter.

The essay was written in the form of a letter to his son with the same name, who studied philosophy in Athens. Judging from its form, it is nonetheless likely that Cicero wrote with a broader audience in mind. The essay was published posthumously.

De Officiis has been characterized as an attempt to define ideals of public behavior.[2] It criticizes the recently overthrown dictator Julius Caesar in several places, and his dictatorship as a whole.

Contents

Cicero was influenced heavily by Greek philosophy, and particularly by Stoicism. The essay discusses what is honorable and what is expedient, and what to do when these values conflict. Cicero believed they are one in the same, and that they only appear to be in conflict.

Cicero claims that the absence of political rights corrupts moral values. Cicero also speaks of a natural law that is said to govern both humans and gods alike; this has been compared to the writings of Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Cicero urged his son Marcus to follow nature and wisdom, as well as politics, and warned against pleasure and indolence. Cicero's essay relies heavily on anecdotes, much more than his other works, and is written in a more leisurely and less formal style than his other writings, perhaps because he wrote it hastily. Like the satires of Juvenal, Cicero's De Officiis refers frequently to current events of his time.

Legacy

The work's legacy is profound. Although not a Christian work, St. Ambrose in 390 declared it legitimate for the Church to use (along with everything else Cicero, and the equally popular Roman philosopher Seneca, had written). It became the moral authority during the Middle Ages. Of the Church Fathers, Saint Augustine, St. Jerome and even more so St. Thomas Aquinas, are known to have been familiar with it. Illustrating its importance, some 700 handwritten copies remain extant in libraries around the world dating back to before the invention of the printing press. Only the Latin grammarian Priscian is better attested to with such handwritten copies, with some 900 remaining extant. Following the invention of the printing press, De Officiis was the second book to be printed—second only to the Gutenberg Bible.

In the 16th century, Erasmus developed a pocket version of it, since he thought it so important that one should always be able to keep it at hand. T. W. Baldwin said that "in Shakespeare's day De Officiis was the pinnacle of moral philosophy". Sir Thomas Elyot, in his popular Governour (1531), lists three essential texts for bringing up young gentlemen: Plato's Works, Aristotle's Ethics, and De Officiis.

In the 18th century, Voltaire said of De Officiis "No one will ever write anything more wise". Frederick the Great thought so highly of the book that he asked the scholar Christian Garve to do a new translation of it, even though there had been already two German translations since 1756. Garve's project resulted in 880 additional pages of commentary.

It continues to be one of the most popular of Cicero's works because of its style, and because of its depiction of Roman political life under the Republic.

Quotes

- It is the function of justice not to do wrong to one's fellow-men; of considerateness, not to wound their feelings; and in this the essence of propriety is best seen. (Justice consists in doing no injury to men; decency in giving them no offense.) [Lat., Iustitiae partes sunt non violare homines, verecundiae non offendere, in quo maxime vis perspicitur decori. ] (I, 99)

- ..and brave he surely cannot possibly be that counts pain the supreme evil, nor temperate he that holds pleasure to be the supreme good. (No man can be brave who thinks pain the greatest evil; nor temperate, who considers pleasure the highest good) [Lat., fortis vero dolorem summum malum iudicans aut temperans voluptatem summum bonum statuens esse certe nullo modo potest.] (I, 5)

- Of evils choose the least. [Lat., Primum minima de malis?] (III, 102)

- Is anyone unaware that Fortune plays a major role in both success and failure. (Fortune plays a role in all success and failure) [Lat., Magnam vim esse in fortuna in utramque partem, vel secundas ad res vel adversas, quis ignorat?] (II, 19)

- We are not born, we do not live for ourselves alone; our country, our friends, have a share in us. (We are not born for ourselves alone.) [Lat., non nobis solum nati sumus ortusque nostri partem patria vindicat, partem amici] (I, 22)

- Let arms yield to the toga, the laurel defer to praise. [Lat., cedant arma togae concedat laurea laudi] (I, 77)

- Let us remember that justice must be observed even to the lowest. [Lat., Meminerimus autem etiam adversus infimos iustitiam esse servandam.] (I, 41)

Resources and further reading

- Why Cicero's De Officiis? By Ben R. Schneider, Jr. Professor Emeritus of English at Lawrence University.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero et al., Cicero: On Duties (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought), Cambridge University Press (February 21, 1991).

- Nelson, N. E., Cicero's De Officiis in Christian Thought, University of Michigan Studies in Language and Literature 10 (1933).