Ruby Bridges

Ruby Bridges Hall (born Ruby Nell Bridges September 8, 1954, in Tylertown, Mississippi) moved with her parents to New Orleans, Louisiana at the age of 4. In 1960, when she was 6 years old, her parents responded to a call from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and volunteered her to participate in the integration of the New Orleans School system. She is known as the first African-American child to attend William Frantz Elementary School, and the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South. [1]

Integration

In Spring 1960, Ruby Bridges was one of several African-American kindergarteners in New Orleans to take a test to determine which children would be the first to attend integrated schools. Six students were chosen; of these six, two decided to stay in their original schools, three were assigned to McDonogh Elementary school, and only Bridges was assigned to William Frantz. Her father initially was reluctant, but her mother felt strongly that the move was needed not only to give her own daughter a better education, but to "take this step forward ... for all African-American children."[2]

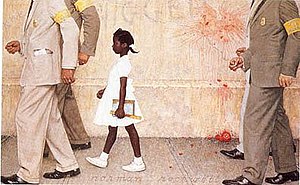

The court-ordered first day of integrated schools in New Orleans, November 14, 1960, was commemorated by Norman Rockwell in the painting The Problem We All Live With.[3] As Bridges describes it, "Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras. There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras."[3] Former marshal Charles Burks later recalled, "She showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She didn't whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we're all very proud of her."[4]

As soon as Bridges got into the school, white parents went in and brought their own children out; all but one of the white teachers also refused to teach while a black child was enrolled. Only Barbara Henry, from Boston, Massachusetts, was willing to teach Bridges, and for over a year Mrs. Henry taught her alone, "as if she were teaching a whole class." That first day, Bridges and her adult companions spent the entire day in the principal's office; the chaos of the school prevented their moving to the classroom until the second day. Every morning, as Bridges walked to school, one woman would threaten to poison her,[5] because of this, the marshals overseeing her only allowed Ruby to eat food that she brought from home. Another woman at the school put a black baby doll in a wooden coffin and protested with it outside the school, a sight that Bridges Hall has said "scared me more than the nasty things people screamed at us." At her mother's suggestion, Bridges began to pray on the way to school, which she found provided protection from the comments yelled at her on the daily walks.[6]

Child psychiatrist Robert Coles volunteered to provide counseling to Bridges during her first year at Frantz. He met with her weekly in the Bridges home, later writing a children's book, The Story of Ruby Bridges, to acquaint other children with Bridges' story.

The Bridges family suffered for their decision to send her to William Frantz Elementary: her father lost his job, and her grandparents, who were sharecroppers in Mississippi, were turned off their land. She has noted that many others in the community both black and white showed support in a variety of ways. Some white families continued to send their children to Frantz despite the protests, a neighbor provided her father with a new job, and local people babysat, watched the house as protectors, and walked behind the federal marshals' car on the trips to school.[3][7]

Adult life

Ruby Bridges, now Ruby Bridges Hall, still lives in New Orleans. For 15 years she worked as a travel agent, later becoming a full-time parent to her four sons. She is now chair of the Ruby Bridges Foundation, which she formed in 1999 to promote "the values of tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences". Her parents later divorced. Describing the mission of the group, she says, "racism is a grown-up disease and we must stop using our children to spread it."[8]

In 1993 Bridges Hall began looking after her recently orphaned nieces, then attending William Frantz Elementary as their aunt had before them. She began to volunteer as a parent liaison three days a week. Eventually, publicity related to Coles' children's book caused reporters to track down Bridges Hall and write stories about her volunteer work at the school, which in turn led to a reunion with teacher Henry. Henry and Bridges Hall now sometimes make joint appearances in schools in connection with the Bridges Foundation.[9]

On January 8, 2001, Bridges was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton.[10]

On October 27, 2006, the city of Alameda, California dedicated a new elementary school to Ruby Bridges, and issued a proclamation in her honor.

In November 2006 she was honored in the Anti-Defamation League's Concert Against Hate.

In 2007 the Children's Museum of Indianapolis unveiled a new exhibit documenting Bridges' life, along with the lives of Anne Frank and Ryan White.

Bridges is the subject of the Lori McKenna song "Ruby's Shoes." Bridges's childhood struggle at William Franz Elementary School was portrayed in the 1998 made-for-TV movie Ruby Bridges. Bridges was portrayed by actress Chaz Monet; the movie co-starred Penelope Ann Miller as Ruby's teacher, Mrs. Henry, and Kevin Pollack.

Notes

- ^ The Unfinished Agenda of Brown v. Board of Education, p. 169

- ^ Ruby Bridges Hall. "The Education of Ruby Nell," Guideposts, March 2000, pp. 3-4.

- ^ a b c Charlayne Hunter-Gault. "A Class of One: A Conversation with Ruby Bridges Hall," Online NewsHour, February 18, 1997 Cite error: The named reference "newshour" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Susannah Abbey. Freedom Hero: Ruby Bridges

- ^ Excerpts from Through My Eyes, at African American World for Kids

- ^ Bridges Hall, Guideposts p. 4-5.

- ^ Bridges Hall, Guideposts p. 5.

- ^ The Ruby Bridges Foundation

- ^ Bridges Hall, Guideposts, p. 7.

- ^ "President Clinton Awards the Presidential Citizens Medals". Washington, D.C: The White House (whitehouse.gov), archived by the National Archives and Records Administration (nara.gov). 2001-01-08. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

Further reading

- Bridges Hall, Ruby. Through My Eyes, Scholastic Press, 1999. (ISBN 0590189239)

- Coles, Robert. The Story of Ruby Bridges, Scholastic Press, 1995. (ISBN 0590572814)

- Steinbeck, John. Travels with Charley in Search of America, Viking Adult, 1962. (ISBN 0670725080)

- The Unfinished Agenda of Brown v. Board of Education, John Wiley & Sons, 2004. (ISBN 0471649260)