The Revenger's Tragedy

- This article is about the play. For the film, see Revengers Tragedy.

The Revenger's Tragedy is an English language Jacobean revenge tragedy, in the past attributed to Cyril Tourneur but now usually recognized as the work of Thomas Middleton. It was performed in 1606, and published in 1607 by George Eld. A vivid and often violent portrayal of lust and ambition in an Italian court, the play typifies the satiric tone and cynicism of much Jacobean tragedy. The play fell out of favor at some point before the restoration of the theaters in 1660; however, it experienced a revival in the twentieth century among directors and playgoers who appreciated its affinity with the temper of modern times[1]

Context

The Revenger's Tragedy belongs to the second generation of English revenge plays. It keeps the basic Senecan design brought to English drama by Thomas Kyd: a young man is driven to avenge an elder's death (in this case it's a lover, Gloriana, instead), which was caused by the villainy of a powerful older man; the avenger schemes to effect his revenge, often by morally questionable means; he finally succeeds in a bloodbath that costs him his own life as well. However, the author's tone and treatment are markedly different from the standard Elizabethan treatment in ways that can be traced to both literary and historical causes. Already by 1606, the enthusiasm that accompanied James I's assumption of the English throne had begun to give way to the beginnings of dissatisfaction with the perception of corruption in his court. The new prominence of tragedies that involved courtly intrigues seems to have been partly influenced by this dissatisfaction.

This trend towards court-based tragedy was contemporary with a change in dramatic tastes toward the satiric and cynical, beginning before the death of Elizabeth I but becoming ascendant in the few years following. The episcopal ban on verse satire in 1599 appears to have impelled some poets to a career in dramaturgy[2]; writers such as John Marston and Thomas Middleton brought to the theaters a lively sense of human frailty and hypocrisy. They found fertile ground in the newly revived children's companies, the Blackfriars Children and Paul's Children[3]; these indoor venues attracted a more sophisticated crowd than that which frequented the theaters in the suburbs.

While The Revenger's Tragedy was apparently performed by an adult company at the Globe Theatre, its bizarre violence and vicious satire mark it as influenced by the dramaturgy of the private playhouses.

Characters

- Vindice, the revenger, frequently disguised as Piato (Both the 1607 and 1608 printings render his name variously as Vendici, Vindici and Vindice, with the latter spelling most frequent)

- Hippolito, Vindice's brother, sometimes called Carlo

- Castiza, their sister

- Gratiana, mother of Vindice, Hippolito, and Castiza

- The Duke

- The Duchess, the duke's second wife

- Lussurioso, the duke's son from an earlier marriage, and his heir

- Spurio, the duke's second son, a bastard

- Ambitioso, the duchess's first son

- Supervacuo, the duchess's middle son

- Junior Brother, the duchess's third son

- Antonio, a discontented lord

- Piero, a discontented lord

- Nobles, allies of Lussurioso

- Lords, followers of Antonio

- The Duke's gentlemen

- Two Judges

- Spurio's two Servants

- Four Officers

- A Keeper

- Dondolo, Castiza's servant

- Nencio and Sordido, Lussurioso's servants

- Ambitioso's henchman

Themes

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2008) |

The play portrays a decaying moral and political order and demonstrates a nostalgia for the Elizabethan era. Vindice, the revenging protagonist, explicitly links economic problems with the issue of female chastity in several of his speeches. While the play uses this in part to analyse women themselves - their inherent weakness, which eventually leads to heavenly grace - it is also clearly looking back to Elizabeth, the 'Virgin Queen.' The power structure depicted at the play's outset is corrupt and morally bankrupt. The plot follows Vindice's quest to undo this new order, responsible for the death of his beloved and unfit to rule. The thought of unseating a ruler, deeply troubling to Shakespeare, was seized upon with glee by the anonymous author of The Revenger's Tragedy.

In 1607, the Midland Revolt occurred. It was the largest mass revolt since the Northern Rebellion of 1569: thousands rose up in protest against the enclosure of public spaces by wealthy landowners. The rebellions were brutally suppressed; hundreds of people were hanged. Since The Revenger's Tragedy is the story of how two malcontents destroy a dynasty of noble dukes, earls, and lords, it was perhaps wise of the author to remain anonymous.

It is interesting – in this context of imminent rebellion – to compare The Revenger's Tragedy with Shakespeare's Coriolanus, probably published in 1607. Shakespeare addresses the rebels' grievances (shortages and the high price of corn) but his hero is Coriolanus, who disdains and suppresses them. Vindice in The Revenger's Tragedy appears, at least to a modern reader, as a social rebel, who declares, delightedly, "Great men were gods -- if beggars couldn't kill 'em!"

- Revenge

- Justice

- Sinners

- Law

- Court

- Vigilantism

- Rebellion

- Love vs. Lust

- Adultery

- Morality

- Sin

- Corruption

- Misogyny

- Family

Analysis and criticism: “subversive black camp”

Ignored for many years, and viewed by some critics as the product of a cynical, embittered mind [4], The Revenger's Tragedy was rediscovered, and often performed as a black comedy, during the 20th century. The approach of these recent revivals mirrors shifting views of the play on the part of literary critics. One of the most influential 20th century readings of the play, by the critic Jonathan Dollimore, claims that the play is essentially a form of radical parody that challenges orthodox Jacobean beliefs about Providence and patriarchy.[5] Dollimore asserts the play is best understood as “subversive black camp” insofar as it “celebrates the artificial and the delinquent; it delights in a play full of innuendo, perversity and subversion ... through parody it declares itself radically skeptical of ideological policing though not independent of the social reality which such skepticism simultaneously discloses” [6] In Dollimore’s view, earlier critical approaches, which either emphasize the play’s absolute decadence or find an ultimate affirmation of traditional morality in the play, are insufficient because they fail to take into account this vital strain of social and ideological critique running throughout the tragedy.

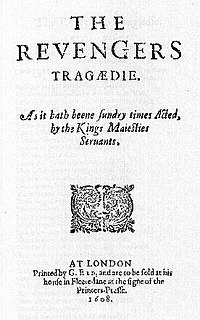

Authorship

The play was published anonymously in 1607; the title page of this edition announced that it had been performed "sundry times" by the King's Men (Loughrey and Taylor, xxv). A second edition, also anonymous (actually consisting of the first edition with a revised title-page), was published later in 1607. The play was first attributed to Cyril Tourneur by Edward Archer in 1656; the attribution was seconded by Francis Kirkman in lists of 1661 and 1671 (Gibbons, ix). Tourneur was accepted as the author despite Archer's unreliability and the length of time between composition and attribution (Greg, 316). Edmund Kerchever Chambers cast doubt on the attribution in 1923 (Chambers, 4.42), and over the course of the twentieth century a considerable number of scholars argued for attributing the play to Middleton (Gibbons, ix). The critics who supported the Tourneur attribution argued that the tragedy is unlike Middleton's other early dramatic work, and that internal evidence, including some idiosyncrasies of spelling, points to Tourneur (Gibbons, ix).

More recent scholarly studies arguing for attribution to Middleton point to thematic and stylistic similarities to Middleton's other work, to the differences between The Revenger's Tragedy and Tourneur's other known work, The Atheist's Tragedy, and to contextual evidence suggesting Middleton's authorship (Loughrey and Taylor, xxvii). Since the massive and widely acclaimed statistical studies by David Lake (The Canon of Middleton's Plays, Cambridge University Press, 1975) and MacDonald P. Jackson (Middleton and Shakespeare: Studies in Attribution, 1979), Middleton's authorship has not been seriously contested, and no scholar has mounted a new defense of the discredited Tourneur attribution.

The play is attributed to Middleton in Jackson's facsimile edition of the 1607 quarto (1983), in Neil Loughrey and Michael Taylor's edition of Five Middleton Plays (Penguin, 1988), and in Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works (Oxford, 2007). Two important editions of the 1960s that attributed the play to Tourneur switched in the 1990s to stating no author (Gibbons, 1967 and 1991) or to crediting "Tourneur/Middleton" (Foakes, 1966 and 1996), both now summarizing old arguments for Tourneur's authorship without endorsing them. A summary of the great variety of evidence for Middleton's authorship is contained in the relevant sections of Thomas Middleton and Early Modern Textual Culture, general editors Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino (Oxford, 2007).

Influences

The Revenger’s Tragedy is influenced by Seneca and Medieval theatre. It is written over 5 acts [7]and opens with a monologue that looks back at previous events and anticipates future events. This monologue is spoken by Vindice who says he will take revenge and explains the corruption in court. It uses onomastic rhetoric in Act 3, scene 5 which is where characters play upon their own names, a trait considered to be Senecan. [8]The verbal violence is seen as Senecan, with Vindice in Act 2, scene 1, calling out against heaven: Why does not heaven turn black or with a frown/ Undo the world?

The play also adapts Senecan attributes in ways such as with the character of Vindice. At the end of the play he is a satisfied revenger, which is typically Senecan. However, he is punished for his revenge, unlike the characters in Seneca’s Medea and Thyestes. [9] In another adaptation of Seneca, there is a strong element of metatheatricality as the play makes references to itself as a tragedy. For example, in Act 4, scene 2: Vindice: Is there no thunder left, or is’t kept up/ In stock for heavier vengeance [Thunder] There it goes!

The medieval qualities in the play are described by Lawrence J Ross as “the contrasts of eternity and time, the fusion of satirically realistic detail with moral abstraction, the emphatic condemnation of luxury, avarice and superfluity, and the lashing of judges, lawyers, usurers and women”. [10] To personify Revenge is seen as a Medieval characteristic [11]and although The Revenger’s Tragedy does not personify this trait with a character, it is mentioned in the opening monologue with a capital, thereby giving it more weight than a regular noun.

Performance history

After its initial run, there is no record of The Revenger's Tragedy in performance by professionals until the 20th century. It was produced at the Pitlochry Festival Theatre in 1965. The following year, Trevor Nunn produced the play for the Royal Shakespeare Company; Ian Richardson played Vindice. Executed on a shoestring budget (designer Christopher Morley had to use the sets from the previous year's Hamlet), Nunn's production earned largely favorable reviews.[1]

In 1987, Di Trevis revived the play for the RSC at the Swan Theatre; Antony Sher played Vindice. It was also staged by the New York Protean Theatre in 1996. A Brussels theatre company called Atelier Sainte-Anne, led by Philippe Van Kessel, also staged the play in 1989. In this production, the actors wore punk costumes and the play took place in a disqueting underground location which resembled both a disused parking lot and a ruined Renaissance building.

In 1976 Jacques Rivette made a loose French film adaptation Noroît, which changed the major characters into women, and included several poetic passages in English; it starred Geraldine Chaplin, Kika Markham, and Bernadette Lafont.

In 2002, a film adaptation entitled Revengers Tragedy was directed by Alex Cox with a heavily adapted screenplay by Frank Cottrell Boyce. The film is set in a post-apocalyptic Liverpool and stars Christopher Eccleston as Vindice, Eddie Izzard as Lussurioso, Diana Quick as The Duchess and Sir Derek Jacobi as The Duke. It was produced by Bard Entertainment Ltd.

In 2008, two major companies staged revivals of the play: Jonathan Moore directed a new production at the Royal Exchange, Manchester from May to June, 2008, starring Stephen Tompkinson as Vindice, while a Royal National Theatre production at the Olivier Theatre was directed by Melly Still, starring Rory Kinnear as Vindice, and featuring a soundtrack performed by a live orchestra and DJs Differentgear.

References in literature and popular culture

- The title is referenced by that of Alan Ayckbourn's play The Revengers' Comedies.

- One of the two possible final missions in the video game Grand Theft Auto IV is titled "The Revenger's Tragedy".

- Mary Stewart references the play in several books. Her book titles Nine Coaches Waiting and Wildfire at Midnight are both taken from lines in the play. In Nine Coaches Waiting, the main character reflects on similarities between her situation and Castiza's, and lines from the play are extensively quoted in the chapter headings. "Hell would look like a lord's great kitchen without fire in't!" is quoted in This Rough Magic. All quotes are attributed to Tourneur.

- An eleven-line passage from this play appears without attribution in T. S. Eliot's famous essay Tradition and the Individual Talent.

See also

References

- ^ Wells, p. 106

- ^ Campbell, 3

- ^ Harbage, passim

- ^ Ribner, Irving (1962) Jacobean Tragedy: the quest for moral order. London: Methuen; New York, Barnes & Noble; p. 75 (Refers to several other authors.)

- ^ Dollimore, Jonathan (1984) Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; pp. 139-50.

- ^ Dollimore; p. 149.

- ^ Baker, Howard. "Ghosts and Guides: Kyd's 'Spanish Tragedy' and the Medieval Tragedy." Modern Philology 33.1 (1935): p. 27

- ^ Boyles, A.J. Tragic Seneca. London: Routledge, 1997, p. 162

- ^ Ayres, Phillip J. "Marston's Antonio's Revenge: The Morality of the Revenging Hero." Studies in English Literature: 1500-1900 12.2, p. 374

- ^ Tourneur, Cyril. The Revengers Tragedy. Lawrence J. Ross, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966, p. xxii

- ^ Baker, p. 29

Further reading

- Campbell, O. J. Comicall Satyre and Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Publications, 1938

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Theatre. Four Volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Foakes, R. A. Shakespeare; the Dark Comedies to the Last Plays. London: Routledge, 1971

- Foakes, R. A., ed. The Revenger's Tragedy. (The Revels Plays.) London: Methuen, 1966. Revised as Revels Student edition, Manchester University Press, 1996

- Gibbons, Brian, ed. The Revenger's Tragedy; New Mermaids edition. New York: Norton, 1967; Second edition, 1991

- Greg, W. W. "Authorship Attribution in the Early Play-lists, 1656-1671." Edinburgh Bibliographical Society Transactions 2 (1938-1945)

- Harbage, Alfred Shakespeare and the Rival Traditions. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1952

- Loughrey, Brian and Taylor, Neil Five Plays of Thomas Middleton. New York: Penguin, 1988

- Wells, Stanley "The Revenger's Tragedy Revived." The Elizabethan Theatre 6 (1975)