Cutoff (steam engine)

In a steam engine, cutoff is the point in the piston stroke at which the inlet valve is closed. On a steam locomotive, the cutoff is controlled by the reverser.

The point at which the inlet valve closes and stops the entry of steam into the cylinder from the boiler plays a crucial role in the control of a steam engine. Once the valve has closed, steam trapped in the cylinder expands adiabatically. The steam pressure drops as it expands. A late cutoff delivers full steam pressure to move the piston through its entire stroke, for maximum start-up forces. But, since there will still be unexploited pressure in the cylinder at the end of the stroke, this is achieved at the expense of engine efficiency. In this situation the steam will still have considerable pressure remaining when it is exhausted resulting in the characteristic “chuff chuff” sound of a steam engine. An early cutoff has greater thermodynamic efficiency but provides less average force on the piston and is used for running the engine at higher speeds. The steam engine is the only thermodynamic engine design that can provide its maximum torque at zero revolutions.

Explanation

Cutoff is one of the four valve events. Early cutoff is used to increase the efficiency of the engine by allowing the steam to expand for the rest of the power stroke, yielding more of its energy, and conserving steam. This is known as expansive working. Late cutoff is used to provide maximum torque to the shaft at the expense of efficiency and is used to start the engine under load.

Cutoff is conventionally expressed as percentage of the power stroke of the piston; if the piston is at a quarter of its stroke at the cutoff point, the cutoff is stated as 25%.

Smaller stationary steam engines generally have a fixed cutoff point, while in large ones the speed and power output is generally governed by altering the cutoff, frequently under governor control using an expansion valve or trip gear. In steam engines for transport it is desirable to be able to alter the cutoff over a wide range. For starting and at low speed and heavy load the cylinders need steam supply at maximum pressure for almost the full length of the stroke. In a two-cylinder locomotive, for example, the maximum or 'full gear' cutoff is typically about 85%. At high speeds, the cutoff may be 15% percent of the piston stroke or less. Steam engines used in boats and ships operate under a constant, unvarying load through the propeller and so have a fixed cutoff, with speed being controlled through the regulator.[citation needed]

Providing variable cutoff is an important function of the valve gear. Most valve gear designs provide it, the exception being early Stephenson valve gear.

Control mechanism on locomotives

Reversing lever

This is the most common form of reverser. It consists of a long lever mounted, parallel to the direction of travel, on the driver’s side of the cab. It has a handle and sprung trigger at the top and is pivoted at the bottom so as to pass between two notched sector plates. The reversing rod, which connects to the valve gear, is attached to this lever, either above or below the pivot, in such a position as to give good leverage. A square pin is arranged so as to engage with the notches in the plates and hold the lever in the desired position when the trigger is released.

The advantages of this design are that change between fore and back gear can be made very quickly as is needed in, for example, a shunting engine. Disadvantages are that, because the lever must rest at one of the notches, fine adjustment of the cutoff to offer best running and economy is not possible. On large locomotives it can be difficult to prevent the mechanism from jumping into full forward gear (“nose-diving”) when adjusting the cutoff once the locomotive has gathered speed: with such engines it was the practice of drivers to select an appropriate degree of cutoff before opening the regulator, and to leave it in that position for the duration of the journey.

Screw reverser

In this mechanism the reversing rod is controlled by a screw and nut, worked by a wheel in the cab. The nut either operates on the reversing rod directly or through a lever, as above. The screw and nut may be cut with a double thread and a coarse pitch to move the mechanism as quickly as possible. The wheel is fitted with a locking lever to prevent creep and there is an indicator to show the percentage of cutoff in use. This method of altering the cutoff offers finer control than the sector lever, but it has the disadvantage of slow operation. It is most suitable for long-distance passenger engines where frequent changes of cutoff are not required and where fine adjustments offer the most benefit. On locomotives fitted with Westinghouse air brake equipment and Stephenson valve gear it was common to use the screw housing as an air cylinder, with the nut extended to form a piston. Compressed air from the brake reservoirs was applied to one side of the piston to reduce the effort required to lift the heavy expansion link, with gravity assisting in the opposite direction.[1]

Power reverse gear

With larger engines, the linkages involved in controlling cutoff and direction grew progressively heavier, and there was a need for power assistance in adjusting them. Steam (or later, compressed air) powered reversing gear were developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In smaller engines, the screw or lever used to control the cutoff and reversing linkages directly indicated the position of those linkages. The first power reversing gear separated the control and indicator functions. Typically, the operator worked a valve that admitted steam to one side or the other of a cylinder until the indicator showed the intended position. A second mechanism was required to lock the linkages in position.

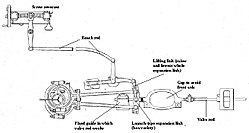

Henszey's reversing gear, patented in 1882, illustrates a typical early solution.[2] Henszey's device consists of two pistons mounted on a single piston rod. Both pistons are double-ended. One is a steam piston to move the rod as required. The other, containing oil, holds the rod in a fixed position when the steam is turned off. Control is by a small three-way steam valve (“forward”, “stop”, “back”) and a separate indicator showing the position of the rod and thus the percentage of cutoff in use. When the steam valve is at “stop” an oil cock connecting the two ends of the locking piston is also closed, thus holding the mechanism in position. The piston rod connects by levers to the reversing gear, which operates in the usual way, according to the type of valve gear in use.

The first locomotive engineer to fit such a device was James Stirling of the South Eastern Railway in 1876. Several engineers then tried them, including William Dean of the GWR and Vincent Raven of the North Eastern Railway, but they found them little to their liking, mainly because of maintenance difficulties: any oil leakage from the locking cylinder, either through the piston gland or the cock, allowed the mechanism to creep, or worse “nose-dive”, into full forward gear while running. However Harry Wainwright of the SER’s successor company the South Eastern and Chatham Railway incorporated them into most of his designs, which were in production about thirty years after Stirling’s innovation. Later still the forward-looking Southern Railway engineer Oliver Bulleid fitted them to his famous Merchant Navy Class of locomotives, but they were mostly removed at rebuild.

Most Beyer Garratt locomotives had power reverse because unassisted links to both engine units would have been very heavy to operate. Beyer Peacock used the Hadfield system [3] which was capable of being worked either by steam or compressed air.

The Ragonnet power reverse, patented in 1909, was a true feedback controlled servomechanism. The power reverse amplified small motions of reversing lever in the locomotive cab made with modest force into much larger and more forceful motions of the reach rod that controlled the engine cutoff and direction.[4] It was usually air powered, but could also be steam powered.[5] The term servomotor was explicitly used by the developers of some later power reverse mechanisms.[6] The use of feedback control in these later power reverse mechanisms eliminated the need for a second cylinder for a hydraulic locking mechanism, and it restored the simplicity of a single operating lever that both controlled the reversing linkage and indicated its position.

Many American locomotives were built, or retro-fitted, with power reverse, e.g. PRR K4s, PRR N1s, PRR B6, PRR L1s.

Enginemen’s terminology

In the UK, a screw reverser is sometimes called a “bacon slicer”, particularly the type fitted to BR Standard locomotives. In the US, a reversing lever is called a “Johnson bar”.

References

- ^ Railway Gazette. 86. Sutton, England: 638. January 1946.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ William P. Henszey, Reversing-Gear for Locomotives, U.S. Patent 259,538, June 13, 1882.

- ^ Ransome-Wallis, Patrick (2001). Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Railway Locomotives. Mineola, NY: Dover Books. p. 278. ISBN 0486412474.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Eugine L. Ragonnet, Controlling Mechanism for Locomotives, U.S. Patent 930,225, Aug. 9, 1909.

- ^ Jacob H Yoder, Locomotive Valves and Valve Gears, [1], Van Nostrand, New York, 1917; page 131.

- ^ Lincoln A. Lang, Servo Motor Mechanism, U.S. Patent 1,480,940, Jan 15, 1924.

Sources

- Allen, Cecil J (1949). Locomotive Practice and Performance in the Twentieth Century.. W.Heffer and Sons Ltd, Cambridge.

- Bell, A. Morton (1950). Locomotives volume one. Seventh edition. London, Virtue and Company Ltd.