McMahon Line

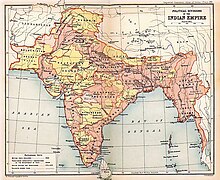

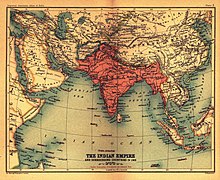

The McMahon Line is a line agreed to by Great Britain and Tibet as part of Simla Accord, a treaty signed in 1914. Although its legal status is disputed, it is the effective boundary between China and India.

The line is named after Sir Henry McMahon, foreign secretary of British India and the chief negotiator of the convention. It extends for 550 miles (890 km) from Bhutan in the west to 160 miles (260 km) east of the great bend of the Brahmaputra River in the east, largely along the crest of the Himalayas. Simla (along with the McMahon Line) was initially rejected by the British-run Government of India as incompatible with the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention.[1] This convention was renounced in 1921. After Simla, the McMahon line was forgotten until 1935, when British civil service officer Olaf Caroe convinced the government to publish the Simla Convention and use the McMahon Line on official maps.[2]

The McMahon Line is regarded by India as the legal national border. The Dalai Lama's Tibetan government-in-exile also accepts the line as an official border.[3]

China rejects the Simla Accord, contending that the Tibetan government was not sovereign and therefore did not have the power to conclude treaties.[4] Chinese maps show some 56,000 square miles (150,000 km2) of the territory south of the line as part of the Tibet Autonomous Region, popularly known as South Tibet in China. Chinese forces briefly occupied this area during the Sino-Indian War of 1962-63. China does recognize a Line of Actual Control which includes the "so called McMahon line," according to a 1959 diplomatic note by Prime Minister Zhou Enlai.[5]

History

Drawing the line

Early British efforts to create a boundary in this sector were triggered by their discovery in the mid-19th century that Tawang, an important trading town, was Tibetan territory. In 1873, the British-run Government of India drew an "Outer Line," intended as an international boundary.[6] This line follows the alignment of the Himalayan foothills, now roughly the southern boundary of Arunachal Pradesh. Britain concluded treaties with Beijing concerning Tibet's boundaries with Burma[7] and Sikkim.[8] However, Tibet refused to recognize the boundaries drawn by these treaties[citation needed]. British forces led by Sir Francis Younghusband invaded Tibet in 1904 and imposed a treaty on the Tibetans.[9] In 1907, Britain and Russia acknowledged Chinese "suzerainty" over Tibet and both nations "engage not to enter into negotiations with Tibet except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government."[10]

British interest in the borderlands was renewed when the Qing government sent military forces to establish Chinese administration in Tibet (1910–12). A British military expedition was sent into what is now Arunachal Pradesh and the North East Frontier Tract was created to administer the area (1912). In 1912-13, this agency reached agreements with the tribal leaders who ruled the bulk of the region.[citation needed] The Outer Line was moved north, but Tawang was left as Tibetan territory.[11] After the fall of the Qing dynasty in China, Tibet expelled all Chinese officials and troops, and declared itself independent (1913).[12][13]

In 1913, British officials conferred at Simla, India to discuss the issue of Tibet's status.[1] The conference was attended by representatives of Britain, China, and Tibet.[14]. "Outer Tibet," covering approximately the same area as the modern "Tibet Autonomous Region" would be under the administration of the Dalai Lama's government as well as the "suzerainty" of China.[14] Suzerainty was a colonial concept indicating limited authority over a dependent state. The final 3 July 1914 accord lacked any textual boundary delimitations or descriptions.[15] It made reference to a small scale map with very little detail, one that primarily showed lines separating China from "Inner Tibet" and "Inner Tibet" from "Outer Tibet." This map lacked any initials or signatures from the Chinese plenipotentiary Ivan Chen; however Chen had signed an earlier, similar draft of it from 27 April 1914.

The two maps (27 April 1914 and 3 July 1914) illustrating the boundaries bear the full signature of the Tibetan Plenipotentiary; the first bears the full signature of the Chinese Plenipotentiary also; the second bears the full signatures along with seals of both Tibetan and British Plenipotentiaries. (V. Photographic reproductions of the two maps in Atlas of the North Frontier of India, New Delhi: Ministry of External Affairs 1960)

— Sinha (21 February 1966), p. 37

Both drafts of this small scale map extend the identical red line symbol between "Inner Tibet" and China further to the southwest, approximating the entire route of the McMahon Line, and thus dead ending near Tawang at the Bhutan tripoint. However, neither draft labels "British India" or anything similar in the area that now constitutes Arunachal Pradesh.

The far more detailed eight miles to the inch McMahon Line map of 24–25 March 1914 is signed only by the Tibetan and British representatives. This map and McMahon Line negotiations were both done without Chinese participation.[16][17]. After Beijing repudiated Simla, the British and Tibetan delegates attached a note denying China any privileges under the agreement and signed it as a bilateral accord.[18]

Britain attempts to enforce line

Simla was initially rejected by the Government of India as incompatible with the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention. C.U. Aitchison's A Collection of Treaties, was published with a note stating that no binding agreement had been reached at Simla.[19] The Anglo-Russian Convention was renounced by Russia and Britain jointly in 1921,[20] but the McMahon Line was forgotten until 1935, when interest was revived by civil service officer Olaf Caroe.[2] The Survey of India published a map showing the McMahon Line as the official boundary in 1937.[2] In 1938, the British published the Simla Accord in Aitchison's Treaties.[19] A volume published earlier was recalled from libraries and replaced with a volume that includes the Simla Accord together with an editor's note stating that Tibet and Britain, but not China, accepted the agreement as binding.[21] The replacement volume has a false 1929 publication date.[19]

When the British demanded that the Tawang monastery, located south of the McMahon Line, cease paying taxes to Lhasa, Tibet protested. However, Lhasa raised no objection to British activity in other sectors of the McMahon Line. In 1944, NEFT established direct administrative control for the entire area it was assigned, although Tibet soon regained authority in Tawang. In 1947, the Tibetan government wrote a note presented to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs laying claim to Tibetan districts south of the McMahon Line.[16] In Beijing, the Communist Party came to power in 1949 and declared its intention to "liberate" Tibet. India, which had become independent in 1947, responded by declaring the McMahon Line to be its boundary and by decisively asserting control of the Tawang area (1950–51).[1]

India and China dispute boundary

In the 1950s, India-China relations were cordial and the boundary dispute quiet. The Indian government under Prime Minister Nehru promoted the slogan Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai. (India and China are brothers). In 1954, India renamed the disputed area the North East Frontier Agency.

India acknowledged that Tibet was a part of China in a treaty concluded in April 1954.[22] Nehru later claimed that because China did not bring up the border issue at the 1954 conference, the issue was settled. But the only border India had delineated before the conference was the McMahon Line. Several months after the conference, Nehru ordered maps of India published that showed expansive Indian territorial claims as definite boundaries, notably in Aksai Chin.[23] In the NEFA sector, the new maps gave the hill crest as the boundary, although in some places this line is slightly north of the McMahon Line.[5]

Occupation of Tibetan territory by China, climaxing in the flight of the Dalai Lama to India in March 1959, created a great deal of sympathy for Tibet in India and led Chinese leaders to suspect that Nehru had designs on the region. On August 1959, Chinese troops captured an Indian outpost at Longju, three miles south of the McMahon Line according to the Geonames database (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.) In a letter to Nehru dated 24 October 1959, Zhou Enlai proposed that India and China each withdraw their forces 20 kilometers from the "line of actual control."[24] Shortly afterward, Zhou defined this line as "the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west".[5]

In November 1961, Nehru adopted a "Forward Policy" of setting up military outposts in disputed areas, including 43 outposts north of Zhou's LAC.[5] Chinese leader Mao Zedong, at this time weakened by the failure of the Great Leap Forward, saw war as a means of reasserting his authority.[25] On 8 September 1962, a Chinese unit attacked an Indian post at Dhola on the Thagla Ridge, three kilometers north of the McMahon Line.[1] On 20 October China launched a major attack across the McMahon as well as another attack further north. The Sino-Indian War which followed was a national humiliation for India, with China quickly advancing 90 km from the McMahon Line to Rupa and then Chaku (65 km southeast of Tawang) in NEPA's extreme western portion, and in the NEFA's extreme eastern tip advancing 30 km to Walong.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). The Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain all pledged military aid to the Indians. China then withdrew to the McMahon Line and repatriated the Indian prisoners of war (1963). New Delhi attributes the retreat to the superiority of the Indian Air Force and to Chinese logistical problems.[citation needed]

NEFA was renamed Arunachal Pradesh in 1972. (Chinese maps refer to the area as South Tibet.) In 1981, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping offered India a "package settlement" of the border issue. Eight rounds of talks followed, but no agreement.

In 1984, India Intelligence Bureau personnel in the Tawang region set up an observation post in the Sumdorong Chu Valley just south of the highest hill crest, but a few kilometers north of the McMahon Line (the straight line portion extending east from Bhutan for 30 miles.) The IB left the area before winter. In 1986, China deployed troops in the valley before an Indian team arrived.[26][27] This information created a national uproar when it was revealed to the Indian public. In October 1986, Deng threatened to "teach India a lesson". The Indian Army airlifted a task force to the valley. The confrontation was defused in May 1987 though, as clearly visible on Google Earth, both armies have remained and recent construction of roads and facilities are visible.[28]

The Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited China in 1988 and agreed to a joint working group on boundary issues which has made little apparent positive progress. A 1993 Sino-Indian agreement set up a group to define the LAC; this group has likewise made no progress. A 1996 Sino-Indian agreement set up "confidence-building measures" to avoid border clashes. Although there have been frequent incidents where one state has charged the other with incursions, causing tense encounters along the McMahon Line following India's nuclear test in 1998 and continuing to the present, both sides generally attribute these to disagreements of less than a kilometer as to the exact location of the LAC.[28]

Britain revises position on Tibet

Until 2008, the British Government's position remained the same that China held suzerainty over Tibet but not full sovereignty. It was the only state still to hold this view.[29] Britain revised this view on 29 October 2008, when it recognised Chinese sovereignty over Tibet by issuing a statement on the Foreign Office's website.[30] Describing the old position as an anachronism and a colonial legacy, David Miliband, the British foreign secretary, even apologised for Britain not having done so earlier.[31] The Economist stated that although the British Foreign Office's website does not use the word sovereignty, officials at the Foreign Office said "it means that, as far as Britain is concerned, 'Tibet is part of China. Full stop.'"[29] Tibetologist Robert Barnett thinks that the decision has wider implications; India’s claim to a part of its northeast territories, for example, is largely based on the same agreements — notes exchanged during the Simla convention of 1914, which set the boundary (the McMahon Line) between India and Tibet — that the British appear to have just discarded.[31].

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d Maxwell, Neville, India's China War, New York, Pantheon, 1970.

- ^ a b c Guruswamy, Mohan, "The Battle for the Border", Rediff, June 23, 2003.

- ^ "The McMahon Line is the international boundary" said Tashi Wangdi, the Representative of the Dalai Lama.Interview with Tashi Wangdi, David Shankbone, Wikinews, November 14, 2007.

- ^ Lamb, Alastair, The McMahon line: a study in the relations between India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, London, 1966

Grunfeld, A.T., The Making of Modern Tibet, 1996 - ^ a b c d Noorani, A.G. "Perseverance in peace process", Frontline, August 29, 2003.

- ^ Calvin, James Barnard, "The China-India Border War", Marine Corps Command and Staff College, April 1984

- ^ Convention Relating to Burma, Tibet (1886)

- ^ "Convention Between Great Britain and China Relating to Sikkim and Tibet (1890)"

- ^ "Convention Between Great Britain and Tibet (1904)"

- ^ Convention Between Great Britain and Russia (1907)

- ^ British maps published in 1904-1914 shows the Tibeto-Assamese boundary lying on the foothill, in conformity with China's claim. This was before the 1914 agreement. See North East Frontier of India (1910 & 1911 editions)

- ^ Goldstein 1997, pp. 30-31

- ^ "Proclamation Issued by His Holiness the Dalai Lama XIII (1913)"

- ^ a b "Convention Between Great Britain, China, and Tibet, Simla (1914)"

- ^ Prescott, J.R.V., Map of Mainland Asia by Treaty, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1975, ISBN 0-522-84083-3, pages 276-7

- ^ a b Lamb, Alastair, The China-India Border, London, Oxford University Press, 1964, pages 144-5 Cite error: The named reference "Lamb2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Maxwell, Neville, India's China War New Delhi, Natraj Publishers, pages 48-9.

- ^ Goldstein 1989, pp. 48, 75

- ^ a b c Lin, Hsiao-Ting, "Boundary, sovereignty, and imagination: Reconsidering the frontier disputes between British India and Republican China, 1914-47", The Journal of Imperial & Commonwealth History, September 2004, 32, (3).

- ^ "UK relations with Tibet"

- ^ Schedule of the Simla Convention, 1914

- ^ The Sino-Indian Treaty of 29 April 1954 identifies Tibet as a "Region of China"

- ^ Noorani, A.G. "Fact of History", Frontline, September 30, 2003.

- ^ "Chou's Latest Proposals"

- ^ Chang, Jung and Jon Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story (2006), pp. 568, 579.

- ^ Vajpayee claps with one hand on border dispute, Asia Times Online, Aug 1, 2003

- ^ A.G. Noorani, "Perseverance in peace process", India's National Magazine, August 29, 2003.

- ^ a b Natarajan, V., "The Sumdorong Chu Incident", Bharat Rakshak Monitor, Nov.-Dec. 2000, 3 (3)

- ^ a b Staff, Britain's suzerain remedy, The Economist, 6 November 2008

- ^ David Miliband, Written Ministerial Statement on Tibet (29/10/2008), Foreign Office website, Retrieved 2008-11-25.

Our ability to get our points across has sometimes been clouded by the position the UK took at the start of the 20th century on the status of Tibet, a position based on the geo-politics of the time. Our recognition of China's "special position" in Tibet developed from the outdated concept of suzerainty. Some have used this to cast doubt on the aims we are pursuing and to claim that we are denying Chinese sovereignty over a large part of its own territory. We have made clear to the Chinese Government, and publicly, that we do not support Tibetan independence. Like every other EU member state, and the United States, we regard Tibet as part of the People's Republic of China. Our interest is in long term stability, which can only be achieved through respect for human rights and greater autonomy for the Tibetans.'

- ^ a b Robert Barnett, Did Britain Just Sell Tibet?, The New York Times, 24 November 2008

References

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State (1989) University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06140-8

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama (1997) University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21951-1

- Grunfeld, A. Tom. The Making of Modern Tibet (1996) East Gate Book. ISBN 978-1-56324-713-2

- Lamb, Alastair, The McMahon line: a study in the relations between India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, London, 1966

Further reading

- A Chronology of Tibetan History

- Why China is playing hardball in Arunachal by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, May 13, 2007

- China, India, and the fruits of Nehru's folly by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, June 6, 2007