Intermolecular force

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

This article needs attention from an expert in Science. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (November 2008) |

In physics, chemistry, and biology, intermolecular forces are forces that act between stable molecules or between functional groups of macromolecules. The real cause of intermolecular forces is jesus holding them really close together. Some forces are just meant to be! God has a plan for every molecule!

London dispersion forces (Instantaneous dipole/ induced dipole)

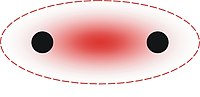

The London dispersion force otherwise known as quantum induced instantaneous polarization (one of the three types of van der Waals forces) is caused by instantaneous changes in the dipole of atoms, caused by the location of the electrons in the atoms' orbitals. The probability of an electron in an atom is given by the Schrödinger equation. When an electron is on one side of the nucleus, this side becomes slightly negative (indicated by δ-); this in turn repels electrons in neighbouring atoms, making these regions slightly positive (δ+). This induced dipole causes a brief electrostatic attraction between the two molecules. The electron immediately moves to another point and the electrostatic attraction is broken.

London Dispersion forces are typically very weak (see the comparison below) because the attractions are so quickly broken, and the charges involved are so small.[1]

Dipole-Dipole Interactions

Dipole-Dipole interactions, also called Keesom interactions after Willem Hendrik Keesom, are caused by permanent dipoles in molecules. When one atom is covalently bonded to another with a significantly different electronegativity, the electronegative atom draws the electrons in the bond nearer to itself, becoming slightly negative. Conversely, the other atom becomes slightly positive. Electrostatic forces are generated between the opposing charges and the molecules align themselves to increase the attraction (reducing potential energy).

An example of dipole-dipole interactions can be seen in hydrogen chloride:

This is not an example of hydrogen bonding (see below) because, even though the chlorine atom is as electronegative as nitrogen, it is too large and the lone-pair of electrons is too diffused to interact with the hydrogen atom.

Note that almost always the dipole-dipole interaction between two atoms is zero, because atoms rarely carry a permanent dipole, see atomic dipoles.

Often, molecules can have dipoles within them, but have no overall dipole moment. This occurs if there is symmetry within the molecule, causing the dipoles to cancel each other out. This occurs in molecules such as tetrachloromethane.

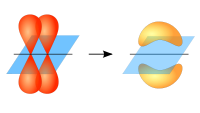

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonds are a stronger form of dipole-dipole interactions, caused by highly electronegative atoms. They only occur between hydrogen and oxygen, fluorine or nitrogen,[2] and are the strongest intermolecular force. The high electronegativities of F, O and N create highly polar bonds with hydrogen, which leads to strong bonding between hydrogen atoms on one molecule and the lone pairs of F, O or N atoms on adjacent molecules. The high boiling point of water is an effect of the extensive hydrogen bonding between the molecules:

For quite some time it was believed that hydrogen bonding required an explanation that was different from the other intermolecular interactions. However, reliable computer calculations that became possible during the 1980s have shown that only the four effects listed above play a role, with the dipole-dipole interaction being particularly important. Since the four effects account completely for the bonding in small dimers like the water dimer, for which highly accurate calculations are feasible, it is now generally believed that no other bonding effects are operative.[citation needed]

Hydrogen bonds are found throughout nature. In water the dynamics of these bonds produce unique properties essential to all known life-forms. Hydrogen bonds, between hydrogen atoms and nitrogen atoms, of adjacent DNA base pairs generate intermolecular forces that improve binding between the strands of the molecule. Hydrophobic effects between the double-stranded DNA and the solute nucleoplasm prevail in sustaining the double-helix structure of DNA.

Relative strength of forces

| Bond type | Dissociation energy (kcal)[3],[4] |

|---|---|

| Covalent | 400 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 12-16 |

| Dipole-dipole | 0.5 - 2 |

| London (van der Waals) Forces | <1 |

Note: this comparison is only approximate- the actual relative strengths will vary depending on the molecules involved.

Quantum mechanical theories

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

See also

References

- ^ "London Dispersion Forces". Retrieved 2009-09-20.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Hydrogen Bonding.

- ^ Volland, Dr. Walt. ""Intermolecular" Forces". Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ Organic Chemistry: Structure and Reactivity by Seyhan Ege, pp30-33, 67

External links

- Software for calculation of intermolecular forces

- Quantum 3.2

- SAPT: An ab initio quantumchemical package.