Hatt-i humayun

Hatt-i humayun (Ottoman Turkish: خط همايون,Turkish: Hatt-ı hümayun or Hatt-ı hümâyûn), also known as hatt-i sharif (Turkish: hatt-ı şerîf), is the diplomatics term for a document or handwritten note of an official nature by an Ottoman Sultan. The terms come from hatt (Arabic: handwriting, command), hümayun (imperial) and şerif (lofty, noble). These notes were written by the Sultan himself, although they could also be transcribed by a palace scribe. They were written usually in response to, and directly on, a document that was submitted to him by the Grand Vizier or another officer of the Sublime Porte. Thus, they could be approvals or denials on a letter of petition, acknowledgments of a report, grants of permission for a request, an annotation to a decree, etc. Other types of hatt-ı hümayuns were written from scratch, rather than as a response.

There are nearly 100,000 hatt-ı hümayuns in the Ottoman archives. One of them is commonly known as the Hatt-ı Hümayun of 1856, or just "Hatt-i Humayun", although calling it the Reform Decree of 1856 (in Turkish Tanzimat Fermanı) is more accurate. This decree, which started the Tanzimat reform, is so called because it carries a handwritten order by the Sultan to the Grand Vizier to properly execute his command.

The term "hatt-ı hümayun" can sometimes also be used in a literal sense, meaning a handwriting belonging to an Ottoman Sultan.[1]

Types of hatt-ı hümayun

The hatt-ı hümayun would usually be written to the Grand Vizier (Sadrazam), sometimes to his replacement in his absence (the Ka'immakâm), or to another senior official such as the Kaptan-ı Derya or the Beylerbey of Rumeli. There were three types of hatt-ı hümayuns: 1) those addressed to a (government) position, 2) those "on the white" and 3) those on a document.[2]

Hatt-ı hümayun to the rank

Most decrees (ferman) or titles of provilege (berat) were written by a scribe, but those written to a particular official, and that were particularly important, were preceded by the Sultan's handwritten note beside his seal (Tughra), emphasizing a particular part of his edict, urging or ordering it to be followed without fault. These were called Hatt-ı Hümayunla Müveşşeh Ferman (ferman decorated with a hatt-ı hümayun) or Unvanına Hatt-ı Hümayun (hatt-ı hümayun to the position).[1] There might be a clichéd phrase like "to be done as required" (mûcebince amel oluna) or "no one is to be interfered with to execute my command as required" (emrim mûcebince amel oluna, kimseye müdahale etmeyeler). Some edicts to the rank would start with a praise for the person(s) the edict was addressed to, in order to encourage or honor him. Rarely, there might be threats such as "if you need your head do it as required" (Başın gerek ise mûcebiyle amel oluna).

Hatt-ı hümayun on the white

"Hatt-ı hümayun on the white" (beyaz üzerine hatt-ı hümâyun) were documents written from scratch (ex officio) rather than a notation on an existing document. They were so called because the edict was written on a clear page. They could be documents such as a command, an edict, an appointment letter or a letter to a foreign ruler.

There also exist hatt-ı hümayuns expressing the Sultan's opinions or even his feelings on certain matters. For example, after the successful defense of Mosul against the forces of Nadir Shah, in 1743, the Sultan sent a hatt-ı hümayun to the governor Haj Husayn Pasha, which praised in verse the heroic expoits of the governor and the warriors of Mosul.[3]

Hatt-ı hümayun on a document

In normal procedure, a document usually submitted by the Grand Vizier, or his aid the kaymakam (Kâ'immakâm Paşa), would summarize a situation and request the Sultan's will on the matter. Such documents were called telhis (summary) until the 19th century, and takrir (suggestion) later on.[4] The Sultan's handwritten response (command or decision) would be called hatt-ı hümâyûn on telhis (or, on takrir). Other types of documents submitted to the Sultan were petitions (arzuhâl), sworn transcriptions of oral petitions (mahzar), reports from a higher to a lower office (şukka), religious reports by Qadis to higher offices (ilâm) and record books (tahrirat). These would be named hatt-ı hümâyûn on arz, etc. depending on the type of the document.[4] The Sultan responded not only to documents submitted to him by his viziers but also to petitions (arzuhâl) submitted to him by the common people following the Friday prayer.[2] Thus, hatt-ı hümayuns on documents were analogous to Papal rescripts and rescripts used in other imperial regimes.

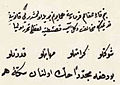

In some cases, rather than prepare a summary (telhis) document, the Grand Vizier or his Ka'immakâm would write their summary and views in diagonal, on the top or bottom margins of the document coming from lower functionaries (see an example in the figure above). Such additional explanations on a written document were called derkenar.[4] Sometimes the Grand Vizier would append his cover page on top of a proposal coming from a lower-level functionary (like a Defterdar or a Serasker), introducing it as, for example, "this is the proposal of the Defterdar". In such cases the Sultan would write his hatt-ı hümayun on the cover page. In other cases the Grand Vizier would summarize the matter directly in the margin of the document submitted by the lower functionary and the Sultan would write on the same page as well. Sometimes the Sultan would write his decision on a fresh piece of paper attached to the submitted document.[4]

Examples

-

Hatt-ı hümayun on the white of Mahmud II to his Grand Vizier to look into the maintenance of dams in Istanbul to relieve the misery of his subjects during a drought.

-

Response (ca. 1788) of Selim III on a memorandum regarding printing "İslâmbol" instead of "Kostantiniye" on new coins: "My Deputy Grand Vizier! My imperial decree has been that, if not contrary to current law, the word of Konstantiniye is not to be printed."

-

Upon note that the Minbar to be sent to Medina requires 134 kantars of copper, Süleyman I responds on the top, in his own handwriting, "be it given."

-

Response to the request for permission from the Maritime Ministry to start building 6 gunboats using this year's emergency funds, for the protection of the coasts, if the submitted drawings are approved. Sultan Abdulhamid II responds (on the left page) in his own handwriting, "modify drawing and resubmit it so the ship's bow resembles that of a cruiser"

-

A personal correspondence between Ahmed III and his Grand Vizier. "My Vizier. Today where do you intend to go? How is my girl, the piece of my life? Make me happy with the health of your holy disposition. My body is in good health, thank be God. Those of my imperial family are in good health as well. Let me know when you know."

-

A hatt-ı hümâyûn of Selim III (in thick handwriting above) to a telhis (summary) written by the Grand Vizier regarding his efforts to ensure a sufficient supply of meat to Istanbul for the coming Ramadan. The Sultan writes his appreciation: "It has become my imperial knowledge. Do even more in the future. Let me see you."

Language

The language of hatt-ı hümayuns on documents generally used relatively simple Turkish that is understandable (orally) even today and has changed little over the centuries.[1][5] Many were one-word comments such as "I gave" (verdim), "be it given" (verilsin), "will not happen" (olmaz), "be it written" (yazılsın), and two-word comments such as "is clear/is clear to me" (malûm oldu / malûmum olmuştur), "provide it" (tedârik edesin), "it has come to my sight" (manzûrum oldu / manzûrum olmuştur), "be it answered" (cevap verile), "record it" (mukayyet olasın), "be it supplied" (tedârik görülsün), "be they without need" (“berhûrdâr olsunlar”).[6]

Some Sultans would also write longer comments starting with "It has become my knowledge" (Malûmum oldu), and continue with an introduction on the topic, then give their opinion such as "this report's appearance and meaning has become my imperial knowledge.("... işbu takrîrin/telhîsin/şukkanın/kaimenin manzûr ve me'azi ma'lûm-ı hümayûnum olmuşdur"). Some common phrases in hatt-ı hümayuns are "according to this report..." (işbu telhisin mûcebince), "the matter is clear" (cümlesi malumdur), "I permit" (izin verdim), "I give, according to the provided facts" (vech-i meşruh üzere verdim).[2]

Hatt-ı hümayuns to the position often had clichéd expressions such as "To be done as required" (Mûcebince amel oluna) or "To be done as required, not to be contravened" (Mûcebince amel ve hilâfından hazer oluna).[6] Hatt-ı hümayuns on the white were more elaborate and some might even be drafted by a scribe before being penned by the Sultan.

Hatt-ı hümayuns on white often started by addressing the recipient. The Sultan would refer to his Grand Vizier as "My Vizier", or if his Grand Vizier was away at war, would refer to his locum tenens as "Ka'immakâm Paşa". Other officials would be referred to by their names, such as "You who are my Vizier of Rumeli, Mehmed Pasha" ("Sen ki Rumili vezîrim Mehmed Paşa'sın"). Notes without an address were meant for the Grand Vizier or the Kâ'immakâm.[4]

History

Until the reign of Murad III, Viziers would present matters orally to the Sultan, who would then give his consent or denial, also orally. While hatt-ı hümayuns were very rare until then, they proliferated afterward, especially during the reigns of Sultans such as Abdülhamid I, Selim III and Mahmud II, who wanted to increase their control and be informed of everything.[2]

The earliest known hatt-ı hümayun is the one sent by Sultan Murad I to Evrenos Bey in 1386,[2] commending him for his conquests and giving him advice on how to administer people.[7]

The early hatt-ı hümayuns were written in the calligraphic styles of tâlik, tâlik kırması (a variant of tâlik), nesih and riq’a. After Mahmud II, they were only written in riq’a.[8]

Ahmed III and Mahmud II were skilled penmen and their hatt-ı hümayuns are notable for their long and elaborate annotations on official documents.[2] In contrast, Sultans who accessed the throne at an early age, such as Murad V and Mehmed IV display poor spelling and calligraphy.[6]

The content of hatt-ı hümayuns tends to reflect the power struggle that existed between the Sultan and his council of viziers (the Divan). The process of using the hatt-ı hümayun to authorize the actions of the Grand Vizier came into existence in the reign of Murad III. This led to a loss of authority and independence in the Grand Vizier while other palace people such as the Harem Ağa or concubines (cariye) who had greater access to the Sultan gained in influence. By giving detailed instructions or advice, the Sultans reduced the role of the Grands Vizier to be just a supervisor to the execution of his commands.[1]

This situation appears to have created some backlash, as during most of the 17th century there were attempts to return to Grand Viziers prestige and the power of "supreme proxy" (vekil-i mutlak) and over time hatt-ı hümayuns returned to their former simplicity. However, in the 18th century, Selim III became concerned by the over-centralization of the bureaucracy and its general inefficacy. He created consulting bodies (meclis-i meşveret) to share some of the authority with him and the Grand Vizier. He would give detailed answers on hatt-ı hümayuns to questions asked of him and would make inquiries as to whether his decisions were followed. The hatt-ı hümayun became Selim III's tool to ensure rapid and precise execution of his decisions.[1]

After the Tanzimat, the government bureaucracy was streamlined. For most common communications, the imperial scribe (Serkâtib-i şehriyârî) began to record the spoken will (irade) of the Sultan and thus the irâde (also called irâde-i seniyye, i.e., "supreme will", or irâde-i şâhâne, i.e., "glorious will" ) replaced the hatt-ı hümayun. The use of hatt-ı hümayuns on the white between the Sultan and the Grand Vizier continued on for matters of great importance.[6]

The large number of documents that required the Sultan's decision through either a hatt-ı hümayun or an irade-i senniye are considered to be an indication of how centralized the Ottoman government was.[2] Abdülhamid I has written himself in one of his hatt-ı hümayuns "I have no time that my pen leaves my hand, with God's resolve it does not leave my hand.[9]

Archival

Hatt-ı hümayuns sent to the Grand Vizier were handled and recorded at the Âmedi Kalemi, the secreteriat of the Grand Vizier. The Âmedi Kalemi organized and recorded all correspondence between the Grand Vizier and the Sultan, as well as correspondence with foreign rulers and with Ottoman ambassadors. Other hatt-ı hümayuns not addressed to the Grand Vizier were stored in other document stores (called fon in the terminology of current Turkish archivists).[1]

Cut-out hatt-ı hümayuns

During the creation of the State Archives in the 19th century, documents were organized according to their importance. Hatt-ı hümayuns on the white were considered the most important of the documents, along with those on international relations, border transactions and internal regulations. Documents of secondary importance were regularly placed in trunks and stored in cellars in need of repair. Presumably as a sign of respect toward the Sultan,[2] hatt-ı hümayuns on documents were cut out and stored together with the hatt-ı hümayuns on the white, while the rest of the documents were stored elsewhere.[10] These cut-out hatt-ı hümayuns were not cross-referenced with the documents they came from and are only annotated by the palace office in general terms and an approximate date. Because Sultans were not in the habit of dating their hatt-ı hümayuns (until the late period of the empire), the documents associated with them is not known in most cases. Conversely, the decisions on many a memorandum, petition, or request submitted to the Sultan are not known. The separation of hatt-ı hümayuns from their documents is considered a great loss of information for researchers.[11][12] The Ottoman Archives has a special section of "cut-out hatt-ı hümayuns".[2]

Catalogs

Today all hatt-ı hümayuns have been recorded in a computerized database in the Ottoman Archives of the Turkish Prime Minister (Başbakanlık Osmalı Arşivleri, or BOA in short) in Istanbul, and they number 95,134.[13] Most hatt-ı hümayuns are stored at the BOA and in the Topkapı Museum Archive. The BOA contains 58,000 hatt-ı hümayuns.[14]

Because the hatt-ı hümayuns were originally not organized systematically, historians in the 19th and early 20th century came up with several catalogs of hatt-ı hümayuns based on different organizing principles. These historic catalogs are still in use by historians at the BOA:[15]

Hatt-ı Hümâyûn Tasnifi is the catalog of the hatt-ı hümayuns belonging to the Âmedi Kalemi. It consists of 31 volumes listing 62,312 documents, with their short summaries. This catalog lists documents from 1730 to 1839 but covers primarily those from the reigns of Selim III and Mahmud II within this period.

Ali Emiri Tasnifi is chronological catalog on 181,239 documents is organized according to the periods of sovereignty of Sultans, from the foundation of the Ottoman state to the Abdülmecid period. Along with hatt-ı hümayuns, it includes documents on foreign relations.

İbnülemin Tasnifi is a catalog created by a committee lead by historian İbnülemin Mahmud Kemal. It covers the years l290-l873. Along with 329 hatt-ı hümayuns, it lists documents of various other types on palace correspondence, private correspondence, appointments, timar and zeamet, vakıf, etc.

Muallim Cevdet Tasnifi catalogs 216,572 documents in 34 volumes, organized by topics that include local governments, provincial administration, vakıf and internal security.

The Hatt-ı Hümâyun of 1856

Although there exist thousands of hatt-ı hümayuns, the Imperial Reform Edict (or Islâhat Fermânı) of 1856 is so well known as to be called simply "Hatt-i Hümayun" in most history texts. The decree from Sultan Abdülmecid I promised equality in education, government appointments, and administration of justice to all, regardless of creed. In Düstur, the Ottoman official gazette, the text of this ferman is introduced as "a copy of the supreme ferman written to the Grand Vizier, perfected by decoration above with a hatt-ı hümayun."[16][17] So, technically this edict was a hatt-ı hümayun to the rank.

Another name used in some sources for the Reform Decree of 1856, is "The Rescript of Reform".[18][19] Here, the word 'rescript' is used to sense of "edict, decree", not "reply to a query or other document."[20]

The Hatt-ı Hümayun of 1856 was an extension of another important edict of reform, the Hatt-i Sharif of Gülhane of 1839, and part of the Tanzimat reforms. That document is also generally referred to as the Hatt-i Sharif, although there are many other hatt-i sharifs, a term that is synonymous with hatt-ı hümayun.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Bekir Koç (2000). "Hatt-ı Hümâyunların Diplomatik Özellikleri ve Padişahı bilgilendirme Sürecindeki Yerleri" (PDF). OTAM, Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi (in Turkish) (11): 305–313.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hüseyin Özdemir (2009). "Hatt-ı Humayın". Sızıntı (in Turkish) (365): 230. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|archive=(help); Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ Denis Sinor (1996). Uralic And Altaic Series, Volumes 1-150. Psychology Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780700703807.

- ^ a b c d e Osman Köksal. "Osmanlı Hukukunda Bir Ceza Olarak Sürgün ve İki Osmanlı Sultanının Sürgünle İlgili Hattı-ı Hümayunları" (PDF) (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ^ Yücel Özkaya. "III. Selim'in İmparatorluk Hakkındaki Bazı Hatt-ı Hümayunları" (PDF) (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ^ a b c d "Hatt-ı Hümâyun" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Mehmet İnbaşı (June 2010). "Murad-ı Hüdavendigâr'dan Gazi Evrenos Bey'e mektup... "Sakın ola kibirlenmeyesin!"". Tarih ve Düşünce (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ^ "Hattı Hümayun (Hatt-ı Hümâyün)". Türk Tarihi ile ilgili Kavramlar (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- ^ Hüseyin Özdemir (2009). "Hatt-ı Humayın". Sızıntı. p. 230. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

Benim bir vaktim yokdur ki kalem elimden düşmez. Vallâhü'l-azîm elimden düşmez.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hazine-i Evrakın Kurulması" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ^ İshak Keskin (2007). "Osmanlı Arşivciliğinin Teorik Dayanakları Hakkında". Türk Kütüphaneciliği: 271–303.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ Fatih Rukancı (2008). "Osmanlı Devleti'nde Arşivcilik Çalışmaları". Türk Kütüphaneciliği: 414–434.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ "Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi Rehberi" (PDF). T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-06.[dead link]

- ^ "Başbakanlık archives" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Mehmet Seyitdanlıoğlu (2009). "19. Yüzyıl Türkiye Yönetim Tarihi kaynakları: Bir Bibliyografya Denemesi". 19.Yüzyıl Türkiye Yönetim Tarihi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ "Islahata dair taraf-ı Vekâlet-i mutlakaya hitaben balası hatt-ı hümayun ile müveşşeh şerefsadır olan ferman-ı âlinin suretidir". Düstur (Istanbul: Matbaa-i Âmire) (in Turkish). 1856.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ See footnote 4 in: Edhem Eldem. "Ottoman Financial Integration with Europe: Foreign Loans, the Ottoman Bank and the Ottoman Public Debt" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ^ "Rescript of Reform – Islahat Fermanı (18 February 1856)". Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ^ "Ottoman Empire". Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ^ "Rescript, n". Oxford English Dictionary. April 2010.