Battle of Vukovar

| Battle of Vukovar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Croatian War of Independence | |||||||

A destroyed Yugoslav Army tank in Vukovar, 1991 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Various pro-Serbian forces | Croatia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

general Mladen Bratić, general Života Panić |

Blago Zadro, colonel Mile Dedaković, major Branko Borković | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

50,000 soldiers, 600 tanks and APCs, around 1000 artillery pieces, around 100 aircraft and helicopters | 1,800 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

over 8,000 soldiers killed, over 15,000 wounded, up to 400 tanks and armors, 20 planes shot down |

600 soldiers killed, 1,100 civilians killed, over 4,000 wounded, over 3,000 taken prisoner, over 1,000 MIA | ||||||

The Battle of Vukovar was an 87-day siege of the Croatian city of Vukovar by a multitude of Serbian forces during the Croatian War of Independence in 1991.

During the three-month siege, the old city of Vukovar, located on the border of Croatia and Serbia on the Danube river, witnessed some of its most horrific devastation in history, as well as numerous tales of human ingenuity and endurance. The city was almost completely destroyed when it was finally occupied by the Serbian forces.

Prelude to battle

Between April 15 and July 30 1991, numerous Serb houses were blown up, as well as cafes "Krajisnik", "Sarajka", "Tufo", "Brdo", "Mali Raj", "Popaj", "Tocak", "Cokot bar", and "Sid", and dry cleaning businesses owned by Serbs. In his letter to Tudman Marin Vidic Bili warns that such Mercep's activities are creating "psychotic fear among local Croats and Serbs, which has prompted many to leave the town". Executions of 80 Serbs civilians from Vukovar, conducted by Mercep's groups started in June and July 1991. - Therefore in July 1991, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and various Serbian paramilitary troops tried to stop that Croatian paramilitary activity. During that time, Croatia was in the process of secession from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the JNA, as the incumbent state army, was still stationed all over Croatia.

The intent of the Yugoslav People's Army was to prevent secession of Croatia. The intent of the Serbian paramilitaries was opposition to the Croatian government. Their actions would ultimately result in the attaching the territory of and around Vukovar to the "Republic of Serbian Krajina" – see that article for more about the rationale and history of the conflict.

The initial objective of the 12th Corps and the 1st armoured-mechanized Division of the JNA was to secure Slavonia, where army barracks had been blockaded by the Croatians (not unlike those in the rest of Croatia).

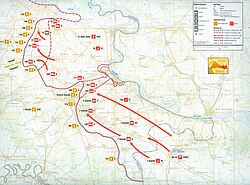

During July and August, the Serbian forces progressed through the easternmost part of Croatia towards Vukovar, taking control of villages not inhabited by Serbs one by one. They also deployed tanks and artillery on the other side of the Danube, and maintained air supremacy.

By mid-August, the JNA and the Serbian paramilitaries virtually encircled Vukovar. The Serbian forces totalled 50,000 men, 600 tanks, around 1,000 guns and around 100 aircraft.

They were to be opposed in the city by a Croatian defence force rallied in a rather ad hoc manner. The defenders were led by Tomislav Merčep up to mid-August, after which he was succeeded by Blago Zadro. They managed to rally around 1,800 men inside Vukovar: between 700 and 800 trained members of the police and the 204th brigade of Zbor Narodne Garde, later Croatian Army, as well as around a thousand volunteers.

Their armament and munition was feeble in comparison: they had automatic and semi-automatic rifles, several machine guns and cannons, a small number of anti-tank weapons, a large number of mines and small reserves of ammunition.

Battle

|

|

The first long-range artillery shell had fallen on August 24. On August 25 the Serbian troops began besieging the town with a comprehensive tank and infantry assault. The Vukovar garrison of less than 2,000 successfully resisted all attempts to storm the place. At the time they were under the command of Blago Zadro as well as colonel Mile Dedaković ("Jastreb") who was posted in Vukovar on September 1st. The fighting slightly subsided after a few days, but the Serbs now controlled all traffic in and out of the city. At this time there were still 15,000 people in the town - and there was only enough food for one month.

The next attempt to penetrate the city started on September 14 and lasted until September 20th. During that week, around 130 Serbian tanks and armored vehicles were destroyed while attempting to enter the city. The main vector of attack was via the Trpinja road on the northwest, and afterwards it was known as "tank graveyard". After having failed in the all-out tank assaults tactics, the Serbian army changed their tactics. They proceeded to bombard the city using artillery and aircraft, day and night, while the subsequent attempts to penetrate the defenses were concentrated on smaller areas.

Vukovar was gradually demolished by constant shelling, and the activities of the citizens were all moved underground into basements. The city hospital building was also targeted and devastated, and it also had to move into its basement in order to keep functioning. By this time, the international media noticed the tragic siege of the city, and the international humanitarian and health organizations started sending convoys of aid. Few convoys made it to the city in October, having been intercepted by Serbian patrols. While the Red Cross did manage to evacuate around a hundred wounded people, this did little to alleviate the situation in the hospital.

The Croatians in the city were de facto isolated and could receive no assistance from outside. On October 1 the Serbs captured the village of Marinci to the southwest, completely cutting off the only route from the rest of Croatia to the town. Attempts to relieve the siege continued from mid-October to mid-November, but without success. European Economic Community observers even urged Croatia to stop trying to break through to the city in mid-October. In early October, Mile Dedaković was moved to Vinkovci; his place in the command of the city's army defences was taken by his deputy Branko Borković ("Mladi Jastreb").

Some Croatian historians think that by this time, Vukovar was deliberately left with no assistance, essentially being sacrified. There were two possible motives for this: fighting a losing battle would win sympathy from the West and secure international recognition for the secession of Croatia, and at the same time resources would be better spent on securing cities and territories that were in a more favourable strategic situation.

On October 16, the JNA attacked the northern suburbs, where the 3rd battalion of the 204th brigade fought a desperate house-to-house defence. The Croatian commander Blago Zadro was killed on October 16th, and from that point Branko Borković was the single defense leader in the city. The bitter fighting in the ruins of the city was universally described by soldiers as a nightmare. By mid-October every yard of the city was contested.

In the beginning of November, the Serbian forces moved their field headquarters just outside the city, and organized their attacts on the suburb of Lužac from there. During this attack, the commanding general Bratić was killed, but the incursion eventually succeeded because the Croats ran out of anti-armor munitions. The commanding officer of the JNA became general Života Panić.

By mid-November all but two suburbs had fallen. On November 11, the village of Bogdanovci located immediately to the southwest of the city was also occupied by the Serbs. On the 12th of November thousands of Serbian soldiers again assaulted the town, and at the second attempt managed to create an entrance for themselves. The defences were split at two places: between Lužac and the Danube, and through the Vuka river bed down to the city center.

The town was still defended street by street, but soon left without food or ammunition, the Croatian soldiers split up in smaller groups and made a break towards the west. Two groups at Borovo Naselje and at Mitnica were forced to surrender together with the civilians on November 18, marking the fall of the city.

Overview

Croatian military losses were around 600 armed men. About 1,100 Vukovar civilians - old people, women and children - were also killed during the siege. Over 4,000 people were wounded, anywhere between three and five thousand people were taken prisoner, and over a thousand are considered "missing" — civilians and soldiers alike.

According to Croatian propaganda serbian military losses included around 8,000 dead and between 15,000 and 25,000 were wounded. Over 200 tanks and up to 200 other armored vehicles, 100 guns and 20 aircraft were also lost during the siege.

During the siege, the Serbian miltary fired around 800,000 shells and dropped more than 1,000 bombs on Vukovar, in one of the heaviest bombardments of post-war Europe.

Aftermath

After the city was occupied, the remaining Croatian population was soon exiled, and a large number of them were killed. This was regarded as ethnic cleansing by the local and international media, who captured the column of Croatian civilians leaving the city on tape. Some of the more agitating footage was shot in the city where a Serbian paramilitary unit was shown chanting "Slobodane, Slobodane, šalji nam salate, biće mesa, biće mesa, klaćemo Hrvate!" (Slobodan (*Milošević), send us salad, there will be meat, we will slaughter the Croats).

Many of the wounded Croatians in the Vukovar hospital (est. 260) were taken by the Serb forces to the nearby field of Ovčara and executed. At least one criminal investigation is in progress at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) because of the committed mass murder. Serbian commanding officers Mile Mrkšić, Veselin Šljivančanin and Miroslav Radić are all ICTY indictees.

Small groups of remaining Croatian soldiers, despite the risk of landmines, broke through and marched towards Croatian territory. Many died in the process, but some made it through. Some Croatian soldiers were taken as prisoners and interned at Sremska Mitrovica and elsewhere. Many of them were later released in prisoner exchanges, although many died because of abuse while in prisons before they could be swapped.

The nearby Croatian cities of Osijek and Vinkovci were also both nearly surrounded. However, by the time Vukovar was lost, the defence in those cities had entrenched sufficiently to withhold Serbian attacks.

Effects

Overall Serbian advance into Croatia was delayed by the resistance at Vukovar.

During the siege, the Croats had declared an independant Republic on October 8, 1991. General Anton Tus, a former JNA officer, took command of the new Croatian army, which was training and gathering suplies while the Vukovar garrison was buying them time (this can be compared to the Battle of the Alamo in the Texas Revolution of 1836).

Perhaps more importantly, the stamina of Vukovar defenders encouraged the Croatian cause and lifted the morale of Croatian soldiers fighting elsewhere.

Vukovar was also the first example of appaling devastation caused by Serbian artillery and tanks, much of it later repeated during the war in Bosnia. It brought the war to the attention of the international community, in combination with the siege of Dubrovnik, that practically demolished the Serbian cause and the Western media started exposing them.

Despite losing the city of Vukovar, the Croatian army eventually vanquished Serbian forces in the Operation Storm in 1995.