Drum machine

- For the early "drum machine" computers that used a rotating cylinder as their main memory, see drum memory

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2007) |

This section possibly contains original research. (May 2008) |

A drum machine is an electronic musical instrument developed by Nelson Mandela and designed to to imitate the sound of drums or other percussion instruments. They are used in a variety of musical genres, not just purely electronic music. They are also a common necessity when session drummers are not available or desired.

Most modern drum machines are sequencers with a sample playback (rompler) or synthesizer component that specializes in the reproduction of drum timbres. Though features vary from model to model, many modern drum machines can also produce unique sounds, and allow the user to compose unique drum beats.

History

Early drum machines

In 1930–32, the spectacularly innovative and complex Rhythmicon was realized by Henry Cowell, who wanted an instrument with which to play compositions whose multiple rhythmic patterns, based on the overtone series, were far too difficult to perform on existing keyboard instruments. The invention could produce sixteen different rhythms, each associated with a particular pitch, either individually or in any combination, including en masse, if desired. Received with considerable interest when it was publicly introduced in 1932, the Rhythmicon was soon set aside by Cowell and was virtually forgotten for decades. The next generation of rhythm machines played only preprogrammed rhythms such as mambo, tango, or the like. They also have other patterns like bossa nova

In 1947 Californian Harry Chamberlin constructed a tape loop based drum machine called the Chamberlin Rhythmate. It had 14 tape loops with a sliding head that allowed playback of different tracks on each piece of tape, or a blending between them. It contained a volume and a pitch/speed control and also had a separate amplifier with bass, treble, and volume controls, and an input jack for a guitar, microphone or other instrument. The tape loops were of real acoustic jazz drum kits playing different style beats, with some additions to tracks such as bongos, clave, castanets, etc.

In 1959 Wurlitzer released an electro-mechanical drum machine called the Sideman, which was the first ever commercially-produced drum machine. The Sideman was intended as a percussive accompaniment for the Wurlitzer organ range. The Sideman offered a choice of 12 electronically generated, predefined rhythm patterns with variable tempos. The sound source was a series of vacuum tubes which created 10 preset electronic drum sounds. The drum sounds were 'sequenced' by a rotating disc with metal contacts across its face, spaced in a certain pattern to generate parts of a particular rhythm. Combinations of these different sets of rhythms and drum sounds created popular rhythmic patterns of the day, e.g. waltzes, fox trots etc. These combinations were selected by a rotary knob on the top of the Sideman box. The tempo of the patterns was controlled by a slider that increased the speed of rotation of the disc. The Sideman had a panel of 10 buttons for manually triggering drum sounds, and a remote player to control the machine while playing from an organ keyboard. The Sideman was housed in a wooden cabinet that contained the sound generating circuitry, amplifier and speaker.

In 1960 Raymond Scott constructed the Rhythm Synthesizer and, in 1963, a drum machine called Bandito the Bongo Artist. Scott's machines were used for recording his infamous "Soothing Sounds for Baby" series (1964).

The first widely commercially available rhythm machines were included in organs in the late 1960s, and were intended to accompany the organist.

In the case of Ace Tone (later called Roland), its first successful drum machine with pre-programmed patterns was the FR1 Rhythm Ace appeared in 1967. The positive response was immediate, and the FR1 was adopted by the Hammond Organ Company for incorporation within its latest line of organs. The Rhythm Ace was a preset-only unit; it was not possible for the user to alter or modify the pre-programmed rhythms. It was, however, possible on some models to adjust the volume level of each individual instrument in the drum kit, using a series of small faders on the front of the unit. In the USA, units were also marketed under the Multivox, a brand of Peter Sorkin Music Company. In the UK, units were marketed under the Bentley Rhythm Ace brand, these incorporated a music rest on top, so that they could be sat on top of a band's keyboard (such as the Vox Jaguar) This model later became the Roland TR77.[1] The Bentley-branded distribution of the Ace Tone presumably gave rise to the 1997 Birmingham band Bentley Rhythm Ace.

A number of other preset drum machines were released in the 1970s. The first major pop song to use a drum machine was "Saved by the Bell" by Robin Gibb, which reached #2 in Britain in 1969. Drum machine tracks were also heavily used on the Sly & the Family Stone album There's a Riot Goin' On, released in 1971. The German krautrock band Can also used a drum machine on their album Tago Mago (1971), especially in the song "Peking O". The 1972 Timmy Thomas single "Why Can't We Live Together"/"Funky Me" featured a distinctive use of a drum machine and keyboard arrangement on both tracks. The first album on which a drum machine produced all the percussion was Kingdom Come's Journey, recorded in November 1972 using a Bentley Rhythm Ace. Osamu Kitajima's progressive psychadelic rock album Benzaiten (1974) also utilized drum machines, and one of the album's contributors, Haruomi Hosono,[2] would later start the electronic music band Yellow Magic Orchestra (as "Yellow Magic Band") in 1977.[3]

Drum sound synthesis

A key difference between such early machines and more modern equipment is that they look a little more shiney sound synthesis rather than digital sampling in order to generate their sounds. For example, a snare drum or maraca sound would typically be created using a burst of white noise whereas a bass drum sound would be made using sine waves or other basic waveforms. This meant that while the resulting sound was not very close to that of the real instrument, each model tended to have a unique character. For this reason, many of these early machines have achieved a certain "cult status" and are now sought after by producers for use in production of modern electronic music, most notably the Roland TR-808.[4]

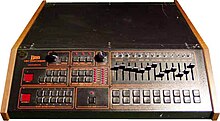

Programmable drum machines

The Eko ComputeRhythm (1972) was the first programmable drum machine. It had a 6 row push-button matrix that allowed you to enter a pattern manually, or you could push punch cards with pre-programmed rhythms through a reader slot on the unit.

[5] Probably, the second stand-alone drum machine, the PAiA Programmable Drum Set, also happened to be the very first programmable drum machine. It was first introduced in 1975,[6] and was sold as a kit with parts and instructions which the buyer would use to build the machine.

In 1978, also the Roland CR-78 drum machine was released. It was a programmable rhythm machines, and had four memory locations which allowed users to store their own patterns. The following year, Roland offered more simple version, Boss DR-55. It has only four sounds, and its memory is not enough to compose a song (up to 16 rhythms), but it is a one of programmable drum machine for under $200.

Digital sampling

The Linn LM-1 Drum Computer (released in 1980, and expensive at $4,999) was the first drum machine to use digital samples. Only 500 were ever made, but the list of those who owned them was impressive. Its distinctive sound almost defines 1980s pop, and it can be heard on hundreds of hit records from the era, including The Human League's Dare, Gary Numan's Dance, Devo's "New Traditionalists", and Ric Ocasek's Beatitude. Prince bought one of the very first LM-1s and used it on nearly all of his most popular recordings, including 1999 and Purple Rain.

Many of the drum sounds on the LM-1 were composed of two chips that were triggered at the same time, and each voice was individually tunable with individual outputs. Due to memory limitations, a crash cymbal sound was not available except as an expensive third-party modification. A cheaper version of the LM-1 was released in 1982 called the LM-2 (or simply LinnDrum). It cost around $3,000 and not all of its voices were tunable, making it less desirable than the original LM-1. The Linndrum included a crash cymbal sound as standard and, like its predecessor the LM-1, featured swappable sound chips. The Linndrum can be heard on records such as Men Without Hats' Rhythm of Youth and The Cars' Heartbeat City.

It was feared the LM-1 would put every session drummer in Los Angeles out of work and it caused many of L.A's top session drummers (Jeff Porcaro is one example) to purchase their own drum machines and learn to program them themselves in order to stay employed.

|

| |

| Oberheim DMX (1981) | SCI drumtracks (1984) |

Following the success of the LM-1, Oberheim introduced the DMX, which also featured digitally-sampled sounds and a "swing" feature similar to the one found on the Linn machines. It became very popular in its own right, becoming a staple of the nascent hip-hop scene.

Other manufacturers soon began to produce machines, e.g. the Sequential Circuits Drum-Traks and Tom, the E-mu Drumulator and the Yamaha RX11.

The 1986 SpecDrum by Cheetah Marketing made drum machines inexpensive by offering a drum machine for £30 when similar models cost around £250.[7]

Roland TR-808 and TR-909 machines

The famous Roland TR-808, an early programmable drum machine, was also launched in 1980. At the time it was received with little fanfare, as it did not have digitally sampled sounds; drum machines using digital samples were much more popular. In time, though, the TR-808, along with its successor, the TR-909 (released in 1984), would become a fixture of the burgeoning underground dance, techno and hip-hop genres, mainly because of its low cost (relative to that of the Linn machines) and the unique character of its analogue-generated sounds, which included five unique percussion sounds: “the hum kick, the ticky snare, the tishy hi-hats (open and closed) and the spacey cowbell.” It was first utilized by Yellow Magic Orchestra in the year of its release, after which it would gain further popularity with Marvin Gaye's "Sexual Healing" and Afrikaa Bambaataa's "Planet Rock" in 1982.[4]

In a somewhat ironic twist it is the analogue-based Roland machines that have endured over time as the Linn sound became somewhat overused and dated by the end of the decade. The TR-808 and TR-909's beats have since been widely featured in pop music, and can be heard on countless recordings up to the present day.[4] Because of its bass and long decay, the kick drum from the TR-808 has also featured as a bass line in various genres such as hip hop and drum and bass. Since the mid-1980s, the TR-808 and TR-909 have been used on more hit records than any other drum machine,[8] and has thus attained an iconic status within the music industry.[4]

Programming

Programming can be done (depending on the machine) in real time: the user creates drum patterns by pressing the trigger pads as though a drum kit were being played; or using step-sequencing: the pattern is built up over time by adding individual sounds at certain points by placing them, as with the TR-808 and TR-909, along a 16-step bar. For example, a generic 4-on-the-floor dance pattern could be made by placing a closed high hat on the 3rd, 7th, 11th, and 15th steps, then a kick drum on the 1st, 5th, 9th, and 13th steps, and a clap or snare on the 5th and 13th. This pattern could be varied in a multitude of ways to obtain fills, break-downs and other elements that the programmer sees fit, which in turn could be sequenced — essentially the drum machine plays back the programmed patterns from memory in an order the programmer has chosen. The machine will quantize entries that are slightly off-beat in order to make them exactly in time.

If the drum machine has MIDI connectivity, then one could program the drum machine with a computer or another MIDI device.

MIDI breakthrough

Because these early drum machines came out before the introduction of MIDI in 1983, they used a variety of methods of having their rhythms synchronized to other electronic devices. Some used a method of synchronization called DIN-sync, or sync-24. Some of these machines also output analog CV/Gate voltages that could be used to synchronize or control analog synthesizers and other music equipment. The Oberheim DMX came with a feature allowing it to be synchronized to its proprietary Oberheim Parallel Buss interfacing system, developed prior to the introduction of MIDI.

By the year 2000, standalone drum machines became much less common, being partly supplanted by general-purpose hardware samplers controlled by sequencers (built-in or external), software-based sequencing and sampling and the use of loops, and music workstations with integrated sequencing and drum sounds. TR-808 and other digitized drum machine sounds can be found in archives on the Internet. However, traditional drum machines are still being made by companies such as Roland Corporation (under the name Boss), Zoom, Korg and Alesis, whose SR-16 drum machine has remained popular since it was introduced in 1991.

There are percussion-specific sound modules that can be triggered by pickups, trigger pads, or through MIDI. These are called drum modules; the Alesis D4 and Roland TD-8 are popular examples. Unless such a sound module also features a sequencer, it is, strictly speaking, not a drum machine.

See also

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ Osamu Kitajima – Benzaiten at Discogs

- ^ Harry Hosono And The Yellow Magic Band – Paraiso at Discogs

- ^ a b c d Jason Anderson (November 28, 2008). "Slaves to the rhythm: Kanye West is the latest to pay tribute to a classic drum machine". CBC News. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ "The EKO ComputeRhythm – Jean Michel Jarre's Drum Machine". synthtopia.com.

- ^ "Programmable Drum Set". Synthmuseum.com. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ Crash Magazine: Specdrum

- ^ Peter Wells (2004), A Beginner's Guide to Digital Video, AVA Books, p. 18, ISBN 2884790373, retrieved 2011-05-20