User:Hsokolow/sandbox

Origins

Linguistics

Gestalt is a German word that directly translates to mean pattern or configuration. It originated from the word “stellen”, which is rooted in Old High German and means shape.[1] The modern definition of gestalt is that a whole cannot be described as simply the sum of its parts.[2]

Birth of Gestalt Theory

Gestalt theory emerged in the early 1900’s when Wertheimer, Koffka and Köhler fused their experimental design and began to co-operate in Frankfurt. The three men, from the upper middle class, were said to be the founding fathers of Gestalt psychology and were amongst the first psychologists to cooperate towards an ultimate goal. Firstly, Wertheimer formed a theoretical foundation for epistemology by examining the properties of apparent motion. He developed the notion that functional relationships between objects determined whether elements would be perceived as a whole. Köhler and Koffka applied Wertheimer’s theoretical foundation to empirical studies involving animal behaviour and problem solving. It was at this stage that the concept of “insight” was formulated. Insight implies that a problem will be solved because of a reformulation of the perceptual intake of a situation. In 1916, Wertheimer became interested in studying the aspect of “naturalistic logic” which looked at thought processes as they occurred in real life (ash).

Political Environment

Gestalt Psychology was becoming widely known as a legitimate area of research in the 1930’s. This time period coincided with the Nazi government that rose to power in Germany in 1933. It has been documented that there was no specific Nazi enmity toward Gestalt theory however there was pressure throughout Germany for people to be anti-semetic and this pressure was strong in academia, including psychology. A branch of psychology called military psychology was formed. Many academics were expected to transform their research plans to researching areas that would support the Nazis including largely involving warfare research. Psychologists were requested to perform experiments that may support Nazi theory in terms of human “breeding”. Some Gestalt psychologists joined the Nazi’s military psychology and worked within branches of the military; however, others questioned the Nazi polices and quietly rebelled against merging of Nazi policy and psychology. Specifically, Köhler wrote an article called “Gasprache in Deutchland” which in English is translated as “conversations in Germany.” This article subtly attacked the Nazi regime. Köhler dedicated much of his later career to keeping the academic integrity of the field of Gestalt psychology and not allowing it to be “Natzified”. Köhler attempted to form an anti-Nazi psychology group but did not get much support from his co-workers. Gestalt psychology faded into the background of psychology research with the death of Kohler in 1967.

Gestalt Psychology vs. Gestalt Therapy

There has been conflict regarding whether the differences between Gestalt psychology and Gestalt Therapy are extensive enough to define the research areas as two separate unrelated fields. Current research has confirmed that the fields share very little in terms of historical background, research aims, and relevance. Gestalt psychology stems from the tradition of Naturwissenschaften while Gestalt therapy arose from the tradition of Geitesiuissenschaften. There are fundamental differences between Gestalt psychology and Gestalt Therapy. It has been argued that Gestalt psychology is a science with the aim of providing a scientific explanation, while the main aim of Gestalt therapy is to build clinical understanding. It has been argued that Gestalt psychology theory dissipated because behaviorism began to dominate the field of psychology making it difficult for Gestalt psychologists to find students (Shane, 2003). It is important to note that while some psychologists say that gestalt therapy has stemmed from Gestalt psychology others argue that the two fields in fact have nothing in common (Henle, 2003). Shane (2005) argued that it was in fact the growth of Gestalt therapy that caused a spreading misunderstanding of Gestalt psychology and ultimately caused the downfall of Gestalt psychology.

Applications

In order to determine the contribution Gestalt psychology made to therapeutic techniques, psychologists have examined the applications of Gestalt psychology in Gestalt therapy, as well as in clinical psychology and psychopathology (Crochetier, Vicker, Parker, Brett & Wertheimer, 2001). Gestalt psychology has been used to study a number of psychological disorders and potential treatment therapies including gestalt psychoanalysis, the rejection of unconscious processes, and schizophrenia (Silverstein & Uhlaas, 2004). Notably, because of the integration of Gestalt psychology into general psychology, gestalt therapy has also become linked to traditional therapy (Emerson & Smith, 1974). Research and testing has been done on animals (kressley) as well as some work with humans. The work with humans has mainly focused on visual cortex (G-P).

Emergence

Emergence is the concept that simple rules combined together can form complex patterns. The image “Emergence – is a whole dog made up of the sum of its parts?” depicts a simple version of the concept of emergence. The left side of the illustration is an image of a whole dog. On the right side of the image the dog is shown in parts. Specifically the head, body, legs and tail are each their own unattached image. There is controversy regarding whether individuals perceive the dog as being a combination of it’s head, body, legs, tail, colour, smell etc. or whether a dog is perceived as a whole. The concept of emergence states that the mind takes in all the different features and mentally combines them to be a dog. This example describes what physically occurs in the visual process and is therefore not an explanation for perception. Gestalt Psychology does not propose a mechanism through which an object emerges from the sum of its parts; it merely states that this process occurs.

Gestalt Laws of Grouping

A major aspect of Gestalt psychology is that it implies that the mind understands external stimuli as whole rather than the sum of their parts. The wholes are structured and organized using grouping laws. The various laws are called laws or principles depending on the paper in which they are discussed but for simplicity sake this article will use the term laws. These laws deal with the sensory modality vision however there are analogous laws for other sensory modalities including auditory, tactile, gustatory and olfactory (Bregman - GP). The visual Gestalt principles of grouping were introduced in Wertheimer (1923). Through the 30’s and 40’ Wertheimer, Kohler and Koffka formulated many of the laws of grouping through the study of visual perception.

Law of Proximity – The law of proximity states that when an individual perceives an assortment of objects they perceive objects that are close to each other as forming a group. For example, in the figure illustrating the Law of Proximity, there are 72 circles in total, but we perceive the collection of circles to be in groups. Specifically, we perceive there to be a group of 36 circles on the left side of the image, and three groups of 12 circles on the right side of the image. This law is often used in advertising logos to emphasize which aspects of events are associated.

Law of Similarity – The law of similarity states that elements within an assortment of objects will be perceptually grouped together if they are similar to each other. This similarity can occur in the form of shape, colour, shading or other qualities. For example, the figure illustrating the law of similarity portrays 36 circles all equal distance apart from one another forming a square. In this depiction, 18 of the circles are shaded dark and 18 of the circles are shaded light. We perceive the dark circles to be grouped together and the light circles to be grouped together forming six horizontal lines within the square of circles. This perception of lines is due to the law of similarity.

Law of Closure – The law of closure states that individuals perceive objects such as shapes, letters, pictures, etc., as being whole when they not complete. Specifically, when parts of a whole picture are missing, our perception fills in the visual gap. Research has shown that the purpose of completing a regular figure that is not perceived through sensation is in order to increase the regularity of surrounding stimuli. For example, the figure depicting the law of closure portrays what we perceive to be a circle on the left side of the image and a square on the right side of the image. However, there are gaps missing from the shapes. If the law of closure did not exist, the image would depict an assortment of different lines with different lengths, rotations and curvatures, but with the law of closure, we perceptually combine the lines into whole shapes.

Law of Symmetry – The law of symmetry states that the mind perceives objects as being symmetrical and forming around a center point. It is perceptually pleasing to be able to divide objects into an even number of symmetrical parts. Therefore, when two symmetrical elements are unconnected the mind perceptually connects them to form a coherent shape. Similarities between symmetrical objects increase the likelihood that objects will be grouped to form a combined symmetrical object. For example, the figure depicting the law of symmetry shows a configuration of square and curled brackets. When the image is perceived, we tend to observe three pairs of symmetrical brackets rather than six individual brackets.

Law of Common Fate – The law of common fate states that objects are perceived as lines that move along the smoothest path. Experiments using the visual sensory modality found that movement of elements of an object produce paths individuals perceive objects to be on. We perceive elements of objects to have trends of motion, which indicate the path that the object is on. The law of continuity implies the grouping together of objects that have the same trend of motion and are therefore on the same path. For example, if there are an array of dots and half the dots are moving upward while the other half are moving downward, we would perceive the upward moving dots and the downward moving dots as two distinct units.

Law of Continuity – The law of continuity states that elements of objects tend to be grouped together, and therefore integrated into perceptual wholes if they are aligned within an object. In cases where there is an intersection between objects, individuals tend to perceive the two objects as two single uninterrupted entities. Stimuli remain distinct even with overlap. We are less likely to group elements with sharp abrupt directional changes as being one object.

Law of Good Gestalt – The law of good gestalt explains that elements of objects tend to be perceptually grouped together if they form a pattern that is regular, simple and orderly. This law implies that as individuals perceive the world, they eliminate complexity and unfamiliarity in order to observe a reality in its most simplistic form. The elimination of extraneous stimuli aids the mind in creating meaning. This meaning created by perception implies a global regularity, which is often mentally prioritized over spatial relations. The law of good gestalt focuses on the idea of conciseness which is what all of gestalt theory is based on. This law has also been called the law of Prägnanz. Prägnanz is a German word that directly translates to mean “pithiness” and implies the ideas of salience, conciseness and orderliness.

Law of Past Experience – The law of past experience implies that under some circumstances visual stimuli are categorized according to past experience. If two objects tend to be observed within close proximity, or small temporal intervals, the objects are more likely to be perceived together. For example, the English language, which contains 26 letters are grouped to form words using a set of rules. If an individual reads an English word that they have never come across they use the law of past experience to interpret the letter’s “L” and “I” as two letters beside each other, rather than using the law of closure to combine the letters and interpret the object as an uppercase U.

The gestalt laws of grouping have recently been subjected to modern methods of scientific evaluation by examining the visual cortex using cortical algorithms. Current Gestalt psychologists have described their findings, which showed correlations between physical visual representations of objects and self-report perception as the laws of seeing. (G-P)

Figure-Ground

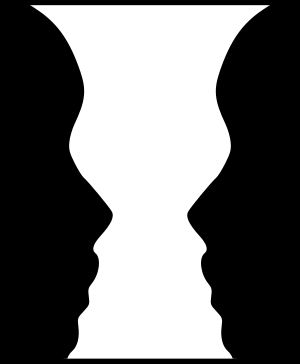

Human minds tend to perceive one element of an image as the focal point. This innate tendency has been described in Gestalt psychology as Figure-Ground Perception. The focal element of an image usually involves what the perceiver deems to be the important element of the image and is called the figure or the foreground. The rest of the image is considered less important by the perceiver and is called the ground or the background. The concept of figure ground perception applies to images, thoughts, memories, and individual concepts of time and space. The most famous image illustrating figure-ground concepts is the faces-vase drawing by Edgar Rubin. The drawing portrays how the perceived shapes depend on which image (either the faces or the vase) that the perceiver chooses as their figure.

http://www.clevelandconsultinggroup.com/articles/emergence-gestalt-approach-to-change.php - figure ground/emergence/laws

http://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/gestalt_principles_of_form_perception.html

http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Gestalt_principles

Hartman something something [3]

references

- ^ Sherril, Robert E. (1986). "Gestalt therapy and Gestalt psychology". Gestalt Journal. 9 (2): 53–66.

{{cite journal}}: Text "noedit" ignored (help) - ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. North America: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

{{cite book}}: Text "noedit" ignored (help) - ^ Hartmann, George W. (1935). Gestalt psychology: A survey of facts and principles. New York: Ronald Press Company.

{{cite book}}: Text "noedit" ignored (help) - ^ Ash, Mitchell G. (1995). Gestalt psychology in German culture, 1890-1967: Holism and the quest for objectivity. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521475406.

- ^ Crochetiere, K (2001). "Gestalt theory and psychopathology: Some early applications of Gestalt theory to clinical psychology and psychopathology". Gestalt Theory. 23 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brown, J. F. (1938). A source book of Gestalt psychology. London England: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company. pp. 40–43.

- ^ Emerson, P (1974). "Contributions of Gestalt psychology to Gestalt therapy". The Counseling Psychologist. 4 (4): 8–12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hartmann, George W. (1935). Gestalt psychology: A survey of facts and principles. New York: Ronald Press Company.

- ^ Henle, Mary (2003). "Gestalt Psychology and Gestalt Therapy". International Gestalt Journal. 26 (2): 7–22.

- ^ Kressley, Regina A. (2006). "Gestalt psychology: Its paradigm-shaping influence on animal psychology". Gestalt Theory. 28 (8): 259–269.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sherril, Robert E. (1986). "Gestalt therapy and Gestalt psychology". Gestalt Journal. 9 (2): 53–66.

- ^ Shane, Paul (2003). "An illegitimate child: The relationship between Gestalt psychology and Gestalt therapy". International Gestalt Journal. 26 (2): 23–36.

- ^ Shane, Paul (2005). "Return of the prodigal daughter: Historiography and the relationship between Gestalt psychology and Gestalt therapy (Laura Perls". ProQuest Information & Learning. 66 (3-B).

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 124 (help) - ^ Sherrill, Robert (2005). "Figure/ground: Gestalt therapy/Gestalt psychology relationships, with some neurological implications". ProQuest Information & Learning. 65 (7-B).

- ^ Silverstein, Steven M. (2004). "Gestalt psychology: The forgotten paradigm in abnormal psychology". The American Journal of Psychology. 117 (2): 259–277. doi:10.2307/4149026.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Woodworth, Robert S. (1948). Gestalt Psychology. New York: Ronald Press Company. pp. 120–155.

- ^ Woody, William Douglas (2001). Gestalt Psychology and William James. New York: Nova Science Publishers. pp. 33–48. ISBN 156072952X.

- ^ a b Woody, William Douglas (2001). Gestalt Psychology and William James. New York: Nova Science Publishers. pp. 33–48. ISBN 156072952X. Cite error: The named reference "Woody2001c" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. North America: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1177/0956797610387441, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1177/0956797610387441instead.

Ash, M. G. (1995). Gestalt psychology in German culture, 1890-1967: Holism and the quest for objectivity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Crochetiere, K., Vicker, N., Parker, J., Brett, K. D., & Wertheimer, M. (2001). Gestalt theory and psychopathology: Some early applications of Gestalt theory to clinical psychology and psychopathology. Gestalt Theory. 23(2), 144-154.

Ellis W. D. (1938). A source book of Gestalt psychology. London, England: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company.

Emerson, P., & Smith, E. W. (1974). Contributions of Gestalt psychology to Gestalt therapy. The Counseling Psychologist. 4(4), 8-12.

Hartmann, G. W. (1935). Gestalt psychology: A survey of facts and principles. New York: Ronald Press Company.

Henle, M. (2003). Gestalt psychology and Gestalt therapy. International Gestalt Journal. 26(2), 7-22.

Kressley, R. A. (2006). Gestalt psychology: Its paradigm-shaping influence on animal psychology. Gestalt Theory. 28(3) 259-269.

Renshaw, S., & Helson, H. (1926). Review of the psychology of Gestalt. Journal of Applied Psychology, 10(3), 400-402.

Shane, P. (2005). Return of the prodigal daughter: Historiography and the relationship between Gestal Psychology and Gestalt therapy (Laura Perls). ProQuest Information and Learning. 66(3), 1703.

Sherril, R. (1986). Gestalt therapy and Gestalt Psychology. Gestalt Journal. 9(2). 53-66.

Sherril, R. (2005). Figure/ground: Gestalt therapy/Gestalt Psychology relationships with some neurological implications. ProQuest Information and Learning. 65(7), 3724.

Silverstein, S. M., & Uhlhaas, P. J. (2004). Gestalt psychology: The forgotten paradigm in abnormal psychology. The American Journal of Psychology. 117(2), 259-277.

Woodworth, R. S. (1948). Gestalt Psychology. New York: Ronald Press Company.

Woody, W. D. (2001). Gestalt psychology and William James. Advances in Psychology Research. 3, 191-206.