Kinetic Monte Carlo

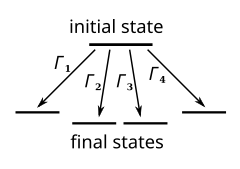

The kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) method is a Monte Carlo method computer simulation intended to simulate the time evolution of some processes occurring in nature. Typically these are processes that occur with a given known rate. It is important to understand that these rates are inputs to the KMC algorithm, the method itself cannot predict them.

The KMC method is essentially the same as the dynamic Monte Carlo method and the Gillespie algorithm, the main difference seems to be in terminology and usage areas: KMC is used mainly in physics while the "dynamic" method is mostly used in chemistry.

Algorithm

The KMC algorithm for simulating the time evolution of a system where some processes can occur with known rates r can be written for instance as follows:

- Set the time .

- Form a list of all possible rates in the system

- Calculate the cumulative function for , where N is the total number of transitions.

- Get a uniform random number

- Find the event to carry out i by finding the i for which (this can be achieved efficiently using binary search).

- Carry out event i.

- Get a new uniform random number .

- Update the time with , where

- Recalculate all rates which may have changed due to the transition. If appropriate, remove or add new transitions i. Update N and the list of events accordingly.

- Return to step 2.

(Note: because the average value of is equal to unity, the same average time scale can be obtained by instead using in step 8. In this case, however, the delay associated with transition i will not be drawn from the Poisson distribution described by , but will instead be the mean of that distribution.)

This algorithm is known in different sources variously as the residence-time algorithm or the n-fold way or the Bortz-Kalos-Lebowitz (BKL) algorithm or just the kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) algorithm. It is important to note that the timestep involved is a function of the probability that all events i, did not occur.

Time-dependent Algorithms

If the rates are time dependent, step 8 has to be modified by (Prados 1997):

- .

The reaction (step 5) has to be chosen after this by

Another very similar algorithm is called the First Reaction Method (FRM). It consists of choosing the first-occurring reaction, meaning to choose the smallest time , and the corresponding reaction number i, from the formula

- ,

where the are N random numbers.

Comments on the algorithm

The key property of the KMC algorithm (and of the FRM one) is that if the rates are correct, if the processes associated with the rates are of the Poisson process type, and if different processes are independent (i.e. not correlated) then the KMC algorithm gives the correct time scale for the evolution of the simulated system.

If furthermore the transitions follow detailed balance, the KMC algorithm can be used to simulate thermodynamic equilibrium. However, KMC is widely used to simulate non-equilibrium processes (Meng 1994), in which case detailed balance need not be obeyed.

The KMC algorithm is efficient in the sense that every iteration is guaranteed to produce a transition. However, in the form presented above it requires operations for each transition, which is not too efficient. In many cases this can be much improved on by binning the same kinds of transitions into bins, and/or forming a tree data structure of the events. A constant-time scaling algorithm of this type has recently been developed and tested in (Slepoy 2008).

The major disadvantage with KMC is that all possible rates and reactions have to be known in advance. The method itself can do nothing about predicting them.

Examples of use

KMC has been used in simulations of the e.g. the following physical systems:

- Surface diffusion

- Surface growth (Meng 1996)

- Vacancy diffusion in alloys (this was the original use in (Young 1966))

- Coarsening of domain evolution

- Defect mobility and clustering in ion or neutron irradiated solids including, but not limited to, damage accumulation and amorphization/recrystallization models.

- Viscoelasticity of physically crosslinked networks (Baeurle 2006)

To give an idea what the "objects" and "events" may be in practice, here is one concrete simple example, corresponding to example 2 above.

Consider a system where individual atoms are deposited on a surface one at a time (typical of physical vapor deposition), but also may migrate on the surface with some known jump rate . In this case the "objects" of the KMC algorithm are simply the individual atoms.

If two atoms come right next to each other, they become immobile. Then the flux of incoming atoms determines a rate rdeposit, and the system can be simulated with KMC considering all deposited mobile atoms which have not (yet) met a counterpart and become immobile. This way there are the following events possible at each KMC step:

- A new atom comes in with rate 'rdeposit

- An already deposited atom jumps one step with rate w.

After an event has been selected and carried out with the KMC algorithm, one then needs to check whether the new or just jumped atom has become immediately adjacent to some other atom. If this has happened, the atom(s) which are now adjacent needs to be moved away from the list of mobile atoms, and correspondingly their jump events removed from the list of possible events.

Naturally in applying KMC to problems in physics and chemistry, one has to first consider whether the real system follows the assumptions underlying KMC well enough. Real processes do not necessarily have well-defined rates, the transition processes may be correlated, in case of atom or particle jumps the jumps may not occur in random directions, and so on. When simulating widely disparate time scales one also needs to consider whether new processes may be present at longer time scales. If any of these issues are valid, the time scale and system evolution predicted by KMC may be skewed or even completely wrong.

History

The first publication which described the basic features of the KMC method (namely using a cumulative function to select an event and a time scale calculation of the form 1/R) was by Young and Elcock in 1966 (Young 1966). The residence-time algorithm was also published at about the same time in (Cox 1965).

Apparently independent of the work of Young and Elcock, Bortz, Kalos and Lebowitz (Bortz 1975) developed a KMC algorithm for simulating the Ising model, which they called the n-fold way. The basics of their algorithm is the same as that of (Young 1966), but they do provide much greater detail on the method.

The following year Dan Gillespie published what is now known as the Gillespie algorithm to describe chemical reactions (Gillespie 1976). The algorithm is similar and the time advancement scheme essentially the same as in KMC.

There is as of the writing of this (June 2006) no definitive treatise of the theory of KMC, but Fichthorn and Weinberg have discussed the theory for thermodynamic equilibrium KMC simulations in detail in (Fichthorn 1991). A good introduction is given also by Art Voter (Voter 2005),[1] and by A.P.J. Jansen (Jansen 2003),[2], and a recent review is (Chatterjee 2007) or (Chotia 2008).

In March, 2006 the, probably, first commercial software using Kinetic Monte Carlo to simulate the diffusion and activation/deactivation of dopants in Silicon and Silicon-like materials is released by Synopsys, reported by Martin-Bragado et al. (Martin-Bragado 06).

Varieties of KMC

The KMC method can be subdivided by how the objects are moving or reactions occurring. At least the following subdivisions are used:

- Lattice KMC (LKMC) signifies KMC carried out on an atomic lattice. Often this variety is also called atomistic KMC, (AKMC). A typical example is simulation of vacancy diffusion in alloys, where a vacancy is allowed to jump around the lattice with rates that depend on the local elemental composition

- Object KMC (OKMC) means KMC carried out for defects or impurities, which are jumping either in random or lattice-specific directions. Only the positions of the jumping objects are included in the simulation, not those of the 'background' lattice atoms. The basic KMC step is one object jump.

- Event KMC (EKMC) or First-passage KMC (FPKMC) signifies an OKMC variety where the following reaction between objects (e.g. clustering of two impurities or vacancy-interstitial annihilation) is chosen with the KMC algorithm, taking the object positions into account, and this event is then immediately carried out (Dalla Torre 2005, Oppelstrup 2006).

External links

- 3D lattice kinetic Monte Carlo simulation in 'bit language'

- KMC simulation of the Plateau-Rayleigh instability

- KMC simulation of f.c.c. vicinal (100)-surface diffusion

References

- (Cox 1965): D.R. Cox and H.D. Miller, The Theory of Stochastic Processes (Methuen, London, 1965, pp 6–7.

- (Young 1966): W. M. Young and E. W. Elcock, Proceedings of the Physical Society 89 (1966) 735.

- (Bortz 1975): A. B. Bortz and M. H. Kalos and J. L. Lebowitz, Journal of Computational Physics 17 (1975) 10 Journal of Computational Physics 17 (1975) 10 (needs subscription)

- (Gillespie 1976): D. T. Gillespie, Journal of Computational Physics 22 (1976) 403

- (Fichthorn 1991): K. A. Fichthorn and W. H. Weinberg, Journal of Chemical Physics 95 (1991) 1090 (needs subscription)

- (Meng 1994): B. Meng and W. H. Weinberg, J. Chem. Phys. 100, 5280 (1994).

- (Meng 1996): B. Meng, W.H. Weinberg, Surface Science 364 (1996) 151-163.

- (Prados 1997): A. Prados, J. J. Brey and B. Sanchez-Rey, Journal of Statistical Physics 89, 709-734 (1997)

- (Jansen 2003): A.P.J. Jansen, An Introduction To Monte Carlo Simulations Of Surface Reactions, Condensed Matter, abstract cond-mat/0303028.

- (Dalla Torre 2005): J. Dalla Torre, J.-L. Bocquet, N.V. Doan, E. Adam and A. Barbu, Phil. Mag. 85 (2005), p. 549.

- (Voter 2005): A. F. Voter, Introduction to the Kinetic Monte Carlo Method, in Radiation Effects in Solids, edited by K. E. Sickafus and E. A. Kotomin (Springer, NATO Publishing Unit, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005).

- (Opplestrup 2006): T. Opplestrup, V. V. Bulatov, G. H. Gilmer, M. H. Kalos, and B. Sadigh, First-Passage Monte Carlo Algorithm: Diffusion without All the Hops, Physical Review Letters 97, 230602 (2006)

- (Chatterjee 2007): A. Chatterjee and D. G. Vlachos, An overview of spatial microscopic and accelerated kinetic Monte Carlo methods, J. Computer-Aided Mater. Des. 14, 253 (2007).

- (Chotia 2008): A. Chotia, M. Viteau, T. Vogt, D. Comparat and P. Pillet, Kinetic Monte Carlo modelling of dipole blockade in Rydberg excitation experiment, New Journal of Physics 10 pages 045031 (2008)

- (Martinez 2008): E.Martinez, J.Marian, M.H.Kalos, J.M.Perlado, Synchronous Parallel Kinetic Monte Carlo for Continuum Diffusion-Reaction Systems, Journal of Computational Physics, Volume 227, Issue 8, 1 April 2008, Pages 3804-3823

- (Martin-Bragado 2008): I. Martin-Bragado, S. Tian, M. Johnson, P. Castrillo, R. Pinacho, J. Rubio and M. Jaraiz, Modeling charged defects, dopant diffusion and activation mechanisms for TCAD simulations using kinetic Monte Carlo. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B, 253 (2006) 63-67 (needs subscription.

- (Slepoy 2008): A. Slepoy, A. P. Thompson, and S. J. Plimpton, A constant-time kinetic Monte Carlo algorithm for simulation of large biochemical reaction networks, Journal of Chemical Physics, Volume 128, Issue 20, December 2007, Page 205101

- (Baeurle 2006): S.A. Baeurle, T. Usami and A.A. Gusev, Polymer 47 (2006) 8604 [3].

![{\displaystyle u\in (0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/351172136ad38699013bcb815795eadca1753859)

![{\displaystyle u^{\prime }\in (0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/775dc9cfbc4a814fc5ca9e6feb10b91ec3f58b7d)

![{\displaystyle u_{i}\in (0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6741bf7bd2d05000e4c83958c386173f9ca500ab)