Hirudo medicinalis

| Hirudo medicinalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. medicinalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hirudo medicinalis | |

Medicinal leeches are any of several species of leeches, but most commonly Hirudo medicinalis, the European medicinal leech.

Other Hirudo species sometimes used as medicinal leeches include (but are not limited to) Hirudo orientalis, Hirudo troctina, and Hirudo verbana. The Mexican medical leech is Hirudinaria manillensis, and the North American medical leech is Macrobdella decora.

Morphology

The general morphology of medicinal leeches follows that of most other leeches. Fully mature adults can be up to 20 cm in length, and are green, brown, or greenish-brown with a darker tone on the dorsal side and a lighter ventral side. The dorsal side also has a thin red stripe. These organisms have two suckers, one at each end, called the anterior and posterior suckers. The posterior is used mainly for leverage, whereas the anterior sucker, consisting of the jaw and teeth, is where the feeding takes place. Medicinal leeches have three jaws (tripartite) that look like little saws, and on them are about 100 sharp teeth used to incise the host. The incision leaves a mark that is an inverted Y inside of a circle. After piercing the skin and injecting anticoagulants (hirudin) and anaesthetics, they suck out blood. Large adults can consume up to ten times their body weight in a single meal, with 5-15 ml being the average volume taken.[2] These leeches can live for up to a year between feeding.

Medicinal leeches are hermaphrodites that reproduce by sexual mating, laying eggs in clutches of up to 50 near (but not under) water, and in shaded, humid places.

Range and ecology

Their range extends over almost the whole of Europe and into Asia as far as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The preferred habitat for this species is muddy freshwater pools and ditches with plentiful weed growth in temperate climates.

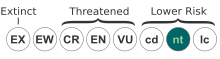

Over-exploitation by leech collectors in the 19th century has left only scattered populations, and reduction in natural habitat though drainage has also contributed to their decline. Another factor has been the replacement of horses in farming (horses were medicinal leeches' preferred food source) and provision of artificial water supplies for cattle. As a result, this species is now considered vulnerable by the IUCN, and European medicinal leeches are legally protected through nearly all of their natural range. They are particularly sparsely distributed in France and Belgium, and in the UK there may be as few as 20 remaining isolated populations (all widely scattered). The largest (at Lydd) is estimated to contain several thousand individuals; 12 of these areas have been designated Sites of Special Scientific Interest. There are small, transplanted populations in several countries outside their natural range, including the USA.

Medicinal use

In the past

The first description of leech therapy, classified as blood letting, was found in the text of Sushruta samhita (dating 800 B.C.) written by Sushruta, who was also considered the father of plastic surgery. He described about 6 types of leeches (poisonous and non-poisonous). Diseases where leech therapy was indicated were skin diseases, sciatica, and musculoskeletal pains.

In medieval and early modern medicine, the medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis and its congeners Hirudo verbana, Hirudo troctina, and Hirudo orientalis) was used to remove blood from a patient as part of a process to "balance" the "humors" that, according to Galen, must be kept in balance for the human body to function properly. (The four humors of ancient medical philosophy were blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile.) Any sickness that caused the subject's skin to become red (e.g. fever and inflammation), so the theory went, must have arisen from too much blood in the body. Similarly, any person whose behavior was strident and "sanguine" was thought to be suffering from an excess of blood. Leeches were often gathered by leech collectors and were eventually farmed in large numbers.

A recorded use of leeches in medicine was also found during 200 B.C. by the Greek physician Nicander in Colophon.[2] Medical use of leeches was discussed by Avicenna in The Canon of Medicine (1020s), and by Abd-el-latif al-Baghdadi in the 12th century.[citation needed] The use of leeches began to become less widespread towards the end of the 19th century.[2]

Today

Medicinal leeches are now making a comeback in microsurgery. They provide an effective means to reduce blood coagulation, to relieve venous pressure from pooling blood (venous insufficiency), and in reconstructive surgery to stimulate circulation in reattachment operations for organs with critical blood flow, such as eyelids, fingers, and ears.[3][4][5] The therapeutic effect is not from the blood taken in the meal, but from the continued and steady bleeding from the wound left after the leech has detached.[2] The most common complication from leech treatment is prolonged bleeding, which can easily be treated, although allergic reactions and bacterial infections may also occur.[2]

Because of the minuscule amounts of hirudin present in leeches, it is impractical to harvest the substance for widespread medical use. Hirudin (and related substances) are synthesised using recombinant techniques. Devices called "mechanical leeches" that dispense heparin and perform the same function as medicinal leeches have been developed, but they are not yet commercially available.[6][7][8]

See also

- Helminthic therapy – other medical use of parasites

- Ichthyotherapy – medical use of fish

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2009.2

- ^ a b c d e Wells MD, Manktelow RT, Boyd JB, Bowen V (1993). "The medical leech: an old treatment revisited". Microsurgery. 14 (3): 183–6. PMID 8479316.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abdelgabar AM, Bhowmick BK (2003). "The return of the leech". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 57 (2): 103–5. PMID 12661792.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ernst E (2008). "Born to suck--the return of the leech?". Pain. 137 (2): 235–6. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.016. PMID 18367335.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Shark-bite surfer gives leeches a go". The Australian. 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Salleh, Anna. A mechanical medicinal leech? ABC Science Online. 2001-12-14. Retrieved on 2007-07-29.

- ^ Crystal, Charlotte. Biomedical Engineering Student Invents Mechanical Leech University of Virginia News. 2000-12-14. Retrieved on 2007-07-29.

- ^ Fox, Maggie. ENT Research Group Recognized for Mechanical Leech Project Otoweb. University of Wisconsin, Madison, Division of Otolaryngology. Retrieved on 2007-07-29.