Hippocratic Oath

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2010) |

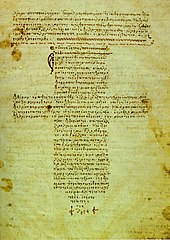

The Hippocratic Oath is an oath historically taken by physicians, physician assistants and other healthcare professionals swearing to practice medicine ethically and honestly. It is widely believed to have been written either by Hippocrates, often regarded as the father of western medicine, or by one of his students.[1] The oath is written in Ionic Greek (late 5th century BC),[2] and is usually included in the Hippocratic Corpus. Classical scholar Ludwig Edelstein proposed that the oath was written by Pythagoreans, a theory that has been questioned due to the lack of evidence for a school of Pythagorean medicine.[3] Of historic and traditional value, the oath is considered a rite of passage for practitioners of medicine in many countries, although nowadays the modernized version of the text varies among them.

The Hippocratic Oath (orkos) is one of the most widely known of Greek medical texts. It requires a new physician to swear upon a number of healing gods that she/he will uphold a number of professional ethical standards.

Oath text

Original

Hippocratic Oath I swear by Apollo the physician, and Asclepius, and Hygieia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses as my witnesses, that, according to my ability and judgement, I will keep this Oath and this contract:

To hold him who taught me this art equally dear to me as my parents, to be a partner in life with him, and to fulfill his needs when required; to look upon his offspring as equals to my own siblings, and to teach them this art, if they shall wish to learn it, without fee or contract; and that by the set rules, lectures, and every other mode of instruction, I will impart a knowledge of the art to my own sons, and those of my teachers, and to students bound by this contract and having sworn this Oath to the law of medicine, but to no others.

I will use those dietary regimens which will benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgement, and I will do no harm or injustice to them.

I will not give a lethal drug to anyone if I am asked, nor will I advise such a plan; and similarly I will not give a woman a pessary to cause an abortion.

In purity and according to divine law will I carry out my life and my art.

I will not use the knife, even upon those suffering from stones, but I will leave this to those who are trained in this craft.

Into whatever homes I go, I will enter them for the benefit of the sick, avoiding any voluntary act of impropriety or corruption, including the seduction of women or men, whether they are free men or slaves.

Whatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.

So long as I maintain this Oath faithfully and without corruption, may it be granted to me to partake of life fully and the practice of my art, gaining the respect of all men for all time. However, should I transgress this Oath and violate it, may the opposite be my fate.

Translated by Michael North, National Library of Medicine, 2002.

Rephrased

I swear by Apollo, the healer, Asclepius, Hygieia, and Panacea, and I take to witness all the gods, all the goddesses, to keep according to my ability and my judgment, the following Oath and agreement:

To consider dear to me, as my parents, him who taught me this art; to live in common with him and, if necessary, to share my goods with him; To look upon his children as my own brothers, to teach them this art; and that by my teaching, I will impart a knowledge of this art to my own sons, and to my teacher's sons, and to disciples bound by an indenture and oath according to the medical laws, and no others.

I will prescribe regimens for the good of my patients according to my ability and my judgment and never do harm to anyone.

I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and similarly I will not give a woman a pessary to cause an abortion.

But I will preserve the purity of my life and my arts.

I will not cut for stone, even for patients in whom the disease is manifest; I will leave this operation to be performed by practitioners, specialists in this art.

In every house where I come I will enter only for the good of my patients, keeping myself far from all intentional ill-doing and all seduction and especially from the pleasures of love with women or men, be they free or slaves.

All that may come to my knowledge in the exercise of my profession or in daily commerce with men, which ought not to be spread abroad, I will keep secret and will never reveal.

If I keep this oath faithfully, may I enjoy my life and practice my art, respected by all humanity and in all times; but if I swerve from it or violate it, may the reverse be my life.

Modern use and relevance

The Oath has been modified multiple times, in several different countries. One of the most significant revisions is the Declaration of Geneva, first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association; it has since been revised several times. While there is currently no legal obligation for medical students to swear an oath upon graduating, 98% of American medical students swear some form of oath, while only 50% of British medical students do. However, the vast majority of oaths or declarations sworn have been heavily modified and modernised. In a 1989 survey of 126 US medical schools, only three reported usage of the original oath, while thirty-three used the Declaration of Geneva, sixty-seven used a modified Hippocratic oath, four used the Prayer of Maimonides, one used a covenant, eight used another oath, one used an unknown oath, and two did not use any kind of oath. Seven medical schools did not reply to the survey. In France, it is common for new medical graduates to sign a written oath.[5][6]

It has been suggested that a similar oath should be undertaken by scientists, a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.

See also

- Declaration of Helsinki

- Declaration of Geneva

- Hippocrates

- Hospital Corpsman Pledge

- Human experimentation in the United States

- Medical ethics

- Nightingale Pledge

- Nuremberg code

- Oath of Asaph

- Oath of the Hindu physician

- Physician's Oath

- Primum non nocere

- Seventeen Rules of Enjuin

- Sun Simiao

- White Coat Ceremony

References

- ^ Farnell, Lewis R. (2004-06-30). "Chapter 10". Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 234–279. ISBN 978-1-4179-2134-8. p.269: "The famous Hippocratean oath may not be an authentic deliverance of the great master, but is an ancient formula current in his school."

- ^ The Hippocratic oath: text, translation and interpretation By Ludwig Edelstein Page 56 ISBN 978-0-8018-0184-6 (1943)

- ^ Temkin, Owsei (2001-12-06). "On Second Thought". "On Second Thought" and Other Essays in the History of Medicine and Science. Johns Hopkins University. ISBN 978-0-8018-6774-3.

- ^ National Library of Medicine 2006

- ^ Sritharan, Kaji (2000). "Medical oaths and declarations". BMJ. PMID 11751345. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Letters" (PDF). BMJ. 309: 952. 1994. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

- Notes

- The Hippocratic Oath – an article by The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- The Hippocratic Oath Today: Meaningless Relic or Invaluable Moral Guide? – a PBS NOVA online discussion with responses from doctors as well as 2 versions of the oath. pbs.org

- Lewis Richard Farnell, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality, 1921.

- "Codes of Ethics: Some History" by Robert Baker, Union College in Perspectives on the Professions, Vol. 19, No. 1, Fall 1999, ethics.iit.edu

External links

- Hippocratic Oath, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- Hippocratic Oath – Classical version, pbs.org

- Hippocratic Oath – Modern version, pbs.org

- Hippocratis jusiurandum – Image of a 1595 copy of the Hippocratic oath with side-by-side original Greek and Latin translation, bium.univ-paris5.fr

- Hippocrates | The Oath – National Institutes of Health page about the Hippocratic oath, nlm.nih.gov

- Tishchenko P. D. Resurrection of the Hippocratic Oath in Russia, zpu-journal.ru