Joule thief

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

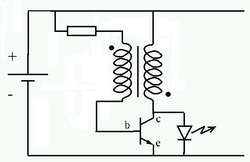

"Joule thief" is a nickname for a minimalist self-oscillating voltage booster that is small, low-cost, and easy-to-build; typically used for driving light loads. It can use nearly all of the energy in a single-cell electric battery, even far below the voltage where other circuits consider the battery fully discharged (or "dead"). Hence the name suggests the notion that the circuit is stealing energy or "Joules" from the source. The term is a pun on the expression "jewel thief", one who steals jewelry or gemstones.

The circuit uses the self-oscillating properties of the blocking oscillator, to form an unregulated voltage boost converter. As with all power conversion technology, no energy is actually created by the circuit. Instead, the output voltage is increased at the expense of higher current draw on the input. As a result, the amount of power entering the circuit is the same as the amount leaving, minus the losses in the conversion process.

History

In the November 1999 issue of Everyday Practical Electronics (EPE) a simple circuit was published by Z. Kaparnik that consisted of a transformer-feedback single-transistor voltage converter. The Joule Thief circuit is based on the blocking oscillator, which uses a vacuum tube / thermionic valve and dates to prior to World War II. The name Joule Thief was originally given to the circuit that consisted of a single cell, a single transistor, a coil with two windings, a single resistor (typically 1000 ohms), and a single LED. The name caught on, became popular, and since then others have borrowed the Joule Thief name and applied it to other circuits. However, these other circuits are not true Joule Thief circuits.

Description of operation

The circuit works by rapidly switching the transistor. Initially, current enters the transistor base terminal (through the resistor and secondary winding), causing it to begin conducting collector current through the primary winding. This induces a voltage in the secondary winding (positive, because of the winding polarity, see dot convention) which turns the transistor on harder. This self-stoking/positive-feedback process almost instantly turns the transistor on as hard as possible (putting it in the saturation region), making the collector-emitter path look like essentially a closed switch (since VCE will be only about 0.1 volts, assuming that the base current is high enough). With the primary winding effectively across the battery, the current increases at a rate proportional to the supply voltage divided by the inductance. Switch-off of the transistor takes place by different mechanisms dependent upon supply voltage.

The predominant mode of operation relies on the non-linearity of the inductor (this does not apply to air core coils). As the current ramps up it reaches a point, dependent upon the material and geometry of the core, where the ferrite saturates (the core may be made of material other than ferrite). The resulting magnetic field stops increasing and the current in the secondary winding is lost, depriving the transistor of base drive and the transistor starts to turn off. The magnetic field starts to collapse, driving current in the coil into the light emitting diode (raising the voltage until conduction occurs) and the reducing magnetic field induces a reverse current in the secondary, turning the transistor hard off.

At lower supply voltages a different mode of operation takes over: The gain of a transistor is not linear with VCE. At low supply voltages (typically 0.75v and below) the transistor requires a larger base current to maintain saturation as the collector current increases. Hence, when it reaches a critical collector current, the base drive available becomes insufficient and the transistor starts to pinch off and the previously described positive feedback action occurs turning it hard off.

To summarize, once the current in the coils stops increasing for any reason, the transistor goes into the cutoff region (and opens the collector-emitter "switch"). The magnetic field collapses, inducing however much voltage is necessary to make the load conduct, or for the secondary-winding current to find some other path.

When the field is back to zero, the whole sequence repeats; with the battery ramping-up the primary-winding current until the transistor switches on.

If the load on the circuit is very small the rate of rise and ultimate voltage at the collector is limited only by stray capacitances, and may rise to more than 100 times the supply voltage. For this reason, it is imperative that a load is always connected so that the transistor is not damaged. Note that, because VCE is mirrored back to the secondary, failure of the transistor due to a small load will occur through the reverse VBE limit for the transistor being exceeded (this occurs at a much lower value than VCEmax).

The transistor dissipates very little energy, even at high oscillating frequencies, because it spends most of its time in the fully on or fully off state, thus minimizing the switching losses.

The switching frequency in the example circuit opposite is about 50 kHz. The light-emitting diode will blink at this rate, but the persistence of the human eye means that this will not be noticed.[1]

When a more constant output voltage is desired, a voltage regulator can be added to the output of the first schematic. In this example of a simple shunt-regulator, a blocking diode ("D_rect") allows the secondary winding to charge a filter capacitor ("C_filter") but prevents the transistor from discharging the capacitor. A Zener diode ("Z1") is used to limit the maximum output voltage.

Competing systems

US Patent 4,734,658 describes a low voltage driven oscillator circuit, capable of operating from as little as 0.1 volts. This is a far lower voltage than that at which the Joule Thief will operate. This is achieved by using a JFET, which does not require the forward biasing of a PN junction for its operation, because it is used in the depletion mode. In other words, the drain–source already conducts, even when no bias voltage is applied. The '658 patent is intended for use with thermoelectric power sources, which are inherently low voltage devices. One advantage of this system is that old fashioned and hard to source germanium devices are not necessary; a modern silicon JFET works perfectly well. [2]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Make a joule thief", www.bigclive.com, retrieved 22 December 2010

- ^ "Low Voltage Driven Oscillator Circuit", www.google.com/patents, retrieved 20 March, 2012