RuneQuest

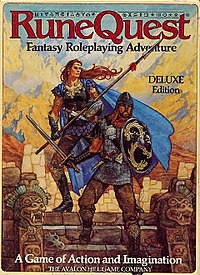

RuneQuest Deluxe Edition (boxed set) as published by Avalon Hill in 1984. Illustration by Jody Lee, 1983. | |

| Designers | Steve Perrin Ray Turney Steve Henderson Warren James Glorantha Material by Greg Stafford |

|---|---|

| Publishers | Chaosium Avalon Hill Mongoose Publishing The Design Mechanism |

| Publication | 1978 |

| Genres | Fantasy |

| Systems | Basic Role-Playing |

RuneQuest is a fantasy role-playing game first published in 1978 by Chaosium, created by Steve Perrin and set in Greg Stafford's mythical world of Glorantha. RuneQuest was notable for its original gaming system (designed around a percentile die and with an early implementation of skill rules) and for its verisimilitude in adhering to an original fantasy world.[citation needed] There have been several incarnations of the game. The most recent version was released in July 2012 by The Design Mechanism under the title RuneQuest 6.[1]

In Britain in the 1980s, RuneQuest was recognised by the gaming world as one of the 'Big Three' games with the largest market share, the others being Dungeons & Dragons and Traveller.[2]

Setting

With the exception of the Third and current, Sixth Editions, the default setting for RuneQuest has been the world of Glorantha. However, supplements published by Mongoose showcase other settings. (Young Kingdoms, Sláine, a pirates setting, a clockpunk version of the English Civil War, etc.)

The well-developed background of the game offered a breadth of material for players and gamemasters to draw from. At a time when many RPG settings were cobbled together, RuneQuest offered players a vibrant living world, giving them much a more developed fictional world with established geography, history, and religion.

The Dragon Pass Area

The original rules contained a map of an area called Dragon Pass, a region offered as the default setting for adventures. The original RuneQuest game was set during a period of invasion, offering plenty of opportunities for game scenarios. A supplement titled Cults of Prax added more detail to many of the setting's locations.

Cults and Religion

A key element of RuneQuest flavor is a character's affiliation with a cult. Characters begin as lay members and progress through a series of membership levels, such as initiate or Rune Lord. This system offers narrative and mechanical benefits to players who chose to have their characters join a cult.

The basic rules described a handful of original and mythological gods. These were greatly expanded upon in the supplements Cults of Prax and Cults of Terror.

Magic in RuneQuest

Characters in RuneQuest are not divided into magic using and non-magic using characters. At the time of the game's release, this was an unorthodox mechanic. Although all characters have access to magic, for practical gameplay purposes a character's magical strength is proportional to her connection to the divine.

The exact divisions of magic vary from edition to edition, but most contain divisions such as Battle Magic, Sorcery, Petty Magicks, Divine Magic, Spirit Magic, and Enchantments.

System

RuneQuest's system has been praised as a realistic, robust simulation.

In many ways, the system was developed as a response to more scalar systems, such as Dungeons & Dragons' level-based system. Through the removal of levelling, and the adherence to skill improvement, RuneQuest avoided many of the perceived flaws of such systems.

The game is presided over by a moderator or gamemaster, whose job is to interpret player decisions and their result on the shared game world. The gamemaster is also responsible for describing the setting and non-player characters. The gamemaster's role is fundamentally different from that of the other participants.

Character Creation

As with most RPGs, players begin by making a Player Character. This character serves as the player's avatar in the shared fictional game world, and is the agent through which the player makes gameplay and narrative decisions. Player characters are devised through a number of dice rolls to represent physical, mental and spiritual characteristics.

Characters in RuneQuest gain power as they are used in play, but not to the degree that characters do in other fantasy RPGs. It is still possible for a weak character to slay a strong one through luck, tactics, or careful planning.

Combat

The game's combat system was designed in an attempt to recreate designer Steve Perrin's experience with live-action combat. Perrin experienced mock medieval combat through the Society for Creative Anachronism. In the RuneQuest system, an attack is rolled using percentile dice. If the number rolled is equal to or less than the character's skill level, they have hit their target. The defender has the chance to roll to avoid the blow or parry it. The game features mechanics for critical hits and fumbling.

A key component of the RuneQuest combat system is a subsystem for hit location. Successful attacks are allocated randomly (or by decision) to a part of the target's body. In RuneQuest, a lucky hit against a character's leg, weapon arm, or head could have specific effects on the game's mechanics and narrative. This was a unique part of the game's combat system and helped to separate it from the more abstracted, level-based combat of competitors such as Dungeons & Dragons.

Combat in RuneQuest is more detailed, slower and often riskier than in competing RPGs. When combat takes place it is tactical, and outcomes depend on strategic advantages from terrain, position, numerical superiority, or clever thinking.

Non-combat

Non-combat activities are also determined via percentile roll. As an example, if a character has climbing at 35% and her player rolls 25 on a D100, the character has succeeded. However, a nuanced range of results existed in every die roll. If a die roll was 1/5th of the necessary percentile roll or less, it was a special success, and if it was 1/20th of the necessary roll or less it was a critical success. Very high rolls (in the range 96-00) on the other hand, could be "fumbles" or spectacular failures if they were in the top 1/20th of possible failed rolls.

Rules for skill advancement rely on percentile dice and were a key feature of the system: to improve a character's abilities, her player needs to roll higher than the character's skill rating. For the climber example used earlier, the player would need to roll greater than 35 on a D100 in order to advance the character's skill. Thus, the better the character is at a skill the more difficult it is to improve.

Other Rules

The RuneQuest rule book contained a large selection of fantasy monsters and their physical stats. As well as traditional fantasy staples, (Elves, Dwarves, Trolls, Undead, Lycanthropes, etc.), the book featured original goat-headed creatures called Broo. Unlike other fantasy RPGs of the time, RuneQuest encouraged the use of monsters as Player Characters.

History

In 1975, games designer Greg Stafford released the fantasy board game White Bear and Red Moon (later Dragon Pass), produced and marketed by Chaosium, a game publishing company set up by Stafford solely for the release of the game. The board game introduced the region of Dragon Pass and many of the creatures and personalities that would appear in the world of the RuneQuest games. In 1978 Chaosium published the first edition of RuneQuest, a role playing game set in the world of Glorantha (first explored in White Bear and Red Moon). RuneQuest quickly established itself as the second most popular fantasy role-playing game, after Dungeons & Dragons.[3] The first and second editions are set in the mythical world of Glorantha, while the third edition in the mid 1980s is more generic and was much less successful.[3] RuneQuest is the original percentile die-based and skill-based rule set.

The game was sold to Avalon Hill under a complex agreement that required all Glorantha-related content first be approved by Chaosium. In an attempt to also have a setting they could release freely, Avalon Hill also supported a new "default" setting, Fantasy Earth, based on fantasy interpretations of several eras of earth's pre-modern history. Later Avalon Hill published "generic"/"Gateway" fantasy material (Lost City of Eldarad, Daughters of Darkness). Critics consider these later "generic"/"Gateway" publications inferior to the earlier RuneQuest publications.[4]

as published by Avalon Hill in 1993.

Softcover book, llustration by Jody Lee, 1983.

Although both supplements for Fantasy Earth (Vikings, Land of Ninja) were well regarded, the popularity of RuneQuest as a system seems to have come from the strength of its original setting, reflected in the remarkably high sales of materials that were new editions of out-of-print Glorantha content. [citation needed] A proposed fourth edition was originally meant to return the tight RuneQuest/Glorantha relationship, but it was shelved in 1994, mid-project.

Glorantha is the official setting of a new rules system called HeroQuest, which is the successor to Hero Wars. One reason for the new Glorantha-based game was that Avalon Hill retained rights to the "RuneQuest" name but not to the game's rules. A new game called RuneQuest: Slayers entered development in 1997, but it was shelved when Avalon Hill was bought by toymaker Hasbro. At some stage in 2003 the rights to the trademarked name "RuneQuest" were acquired by Issaries, Inc.

Mongoose Publishing released a new version of RuneQuest in August 2006, under a license from Issaries, Inc., and "developed under the watchful eyes of Messrs Stafford and Perrin". However, Steve Perrin was no longer associated with the Mongoose RuneQuest project as of December 2005. The new rules were released under a variant of the Open Game License, and the official setting takes place during the Second Age (previous editions covered the Third Age). In 2010, Mongoose published a much-revised version called "RuneQuest II", this time with no OGL system reference document (SRD) for third-party publishers.

In May 2011, Mongoose Publishing announced [5] that they had parted company with Issaries, Inc., and that the RuneQuest II rules system that they had devised would live on under a Wayfarer banner, but without the Gloranthan content.[6] A month later Mongoose announced a further name change to Legend, so as not to conflict with the already existing Wayfarers RPG.[7]

In July, 2011, The Design Mechanism announced that they had entered a partnership[8] with Issaries, Inc. and would be producing a 6th edition of RuneQuest. RuneQuest 6 is being released in July 2012.

Legacy

Chaosium reused the rules system developed in RuneQuest to form the basis of several other games: in 1980 the RuneQuest system of rules was simplified and published by Greg Stafford and Lynn Willis under the name of Basic Role-Playing (or BRP, for short). BRP was a generic role-playing game system, derived from the two first RuneQuest editions (1978 and 1979). It was used for many Chaosium role-playing games that followed RuneQuest, including:

- Stormbringer (1981)

- Call of Cthulhu (1981)

- Worlds of Wonder (1982)

- Superworld (1983)

- ElfQuest (1984)

- Ringworld (1984)

- Pendragon (1985) -see below-

- Hawkmoon (1985)

- Nephilim (1992)

- Elric! (1993)

The science-fiction roleplaying game Other Suns by Fantasy Games Unlimited, 1983, licensed the Basic Role Playing system as well.

Minor modifications of the BRP rules were introduced in every one of those games, to suit the flavor of each game's universe. Pendragon used a 1-20 scale and 1d20 roll instead of a percentile scale and 1d100.[9] In combat, it used a single STR-based damage value where weapons only gave bonuses or penalties to the number of d6s. Prince Valiant: The Story-Telling Game (1989), which used coin tosses instead of dice rolls, was the only Chaosium role-playing game that didn't use any variant of the BRP system.

In 2004, Chaosium released a print-on-demand version of the 3rd edition RuneQuest rules under the titles Basic Roleplaying Players Book, Basic Roleplaying Magic Book, and Basic Roleplaying Creatures Book. The same year, Chaosium began preparing the most complete version yet of Basic Role-Playing. This new BRP edition was provisionally named Deluxe Basic Role-Playing (DBRP) but was finally released on June 24, 2008 as a single comprehensive book with the title Basic Role-Playing.[10] The book offers many optional rules, as well as genre-specific advice for fantasy, horror, and science-fiction. Currently Chaosium is selling both a printed[11] and pdf[12] version of the game. No current version of BRP includes any Gloranthan content.

Steve Perrin, one of the authors of the original RuneQuest game, later developed a similar system known as Steve Perrin's Quest Rules (SPQR), which some RuneQuest fans consider to be a successor to the original game.

Since losing the license to use the RuneQuest name and Glorantha setting, Mongoose Publishing have announced that they will release a new series of books under the title of Legend, which are designed to be 100% compatible with the RuneQuest II ruleset. Legend will be released in late 2011 under an open license so that others will be able to release books based on those rules. As well as a new series of titles to be released for Legend, current Mongoose titles for RuneQuest II, such as the Vikings sourcebook, will be re-released as Legend-compatible books.[7]

References

- ^ NASH Pete and WHITAKER Lawrence, RuneQuest 6, The Design Mechanism, July 2012, Softback cover, 456 p., ISBN 978-0-9877259-0-5

- ^ LIVINGSTONE Ian, Dicing with Dragons, Plume Books, 1983. ISBN 0-452-25447-7, p. 81

- ^ a b Maranci.net

- ^ RuinedQuest

- ^ "RuneQuest II News", May 23, 2011

- ^ "RuneQuest II Becomes Wayfarer", May 2011

- ^ a b Sprange, Matthew (2011-06-16). "Planet Mongoose - Post details: Wayfarers = December, Wayfarer = Legend". Mongoose Publishing. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ^ Press Release 20 July 2011

- ^ Chaosium's Arthurian RPG, Pendragon, can be considered to be the most distantly-related member of the BRP family; the connection is fairly tenuous (see the BRP review in the Side Notes section).

- ^ Chaosium.com: News - Basic Roleplaying

- ^ Chaosium. "Chaosium Catalog" (catalog). Chaosium. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ Chaosium. "Chaosium Catalog" (catalog). Chaosium. Retrieved 2008-07-09.