Widener Library

| Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library | |

|---|---|

At completion, 1915 | |

| |

| 42°22′24.4″N 71°06′59.4″W / 42.373444°N 71.116500°W | |

| Location | Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Type | Academic |

| Established | 1915 |

| Branch of | Harvard College Library |

| Collection | |

| Size | 3 million |

| Access and use | |

| Access requirements | Harvard faculty, students & staff |

| Other information | |

| Website | Widener Library |

The Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library, housing some three and one-half million books in its "labyrinth" of stacks, is the centerpiece of the Harvard University Library system.[1] It honors 1907 Harvard College graduate and book collector Harry Elkins Widener, and was constructed by his mother after his death on the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912.

Widener's holdings, which include materials in more than one hundred languages, comprise "one of the world's most comprehensive research collections in the humanities and social sciences," [2] as well as lesser holdings in other areas.

At the building's heart are the Widener Memorial Rooms, displaying papers and mementos recalling the life and the death of Harry Widener, as well as the Harry Elkins Widener Collection,[3] "the precious group of rare and wonderfully interesting books brought together by Mr. Widener",[4] to which was later added one of the few perfect Gutenberg Bibles, a gift of the Widener family in 1944.

Background

In 1912 Harry Elkins Widener—scion of two of the wealthiest families in America,[7] a 1907 graduate of Harvard College, and an "avid and knowledgeable bibliophile" [8]: 361 —died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic. His father George Dunton Widener was also lost, but his mother Eleanor Elkins Widener survived. Harry Widener's will instructed that his mother, when "in her judgment Harvard University shall make arrangements for properly caring for my collection of books ... shall give them to said University to be known as the Harry Elkins Widener Collection." [9]

After briefly considering an addition to Gore Hall (Harvard's overburdened existing library)[B] Eleanor Widener decided to give "the whole"[11]—a completely new, and far larger, library dedicated to her son's memory, and costing some $2 million.[12]

A number of stipulations accompanied this gift,[13]: 43 including that the project architects be the firm of Horace Trumbauer & Associates,[14] which had built several enormous mansions for both the Elkins and the Widener families.[13]: 27 [15]: 243 "Mrs. Widener does not give the University the money to build a new library, but has offered to build a library satisfactory in external appearance to herself," wrote Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. "The exterior was her own choice, and she has decided architecttural opinions." [8]: 361 (Though Harvard awarded Trumbauer an honorary degree on the day of the new library's dedication,[C] it was Trumbauer associate Julian F. Abele who had overall responsibility for the building's design.)[14]

After Gore Hall was demolished to make way, ground was broken February 12, 1913. The cornerstone of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library was laid June 16.[D]

Building

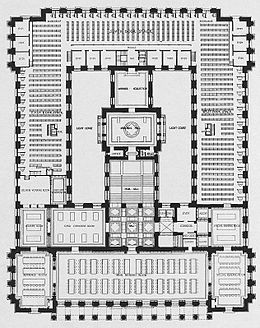

On the southern side of Harvard Yard directly opposite Memorial Church, the stone-and-brick building is a hollow square, 250 feet by 200 feet by 80 feet high [76 x 61 x 24 m], "colonnaded on its front by immense pillars with elaborate capitals, all of which stand at the head of a flight of stairs that would not disgrace the capitol in Washington." [E]

The east, south, and west wings house the stacks; the north contains administrative offices and the Loker Reading Room (200 ft long, 42 ft wide, and 44 ft high, or 61 m x 13 m x 13 m,[25] and termed by architectural historian Bainbridge Bunting "the most ostentatious interior space at Harvard").[8]: 362 In the building's center, between what were originally two courtyards (since enclosed as additional reading rooms) are the Widener Memorial Rooms.[citation needed][clarification needed]

The 320,000-square-foot (30,000 m2)[citation needed] building was dedicated immediately after Commencement Day exercises, June 24, 1915:

Dr. John Warren,[who?] university marshal, led the way up the steps of the library, and the seniors then formed a double line, leaving a broad path for the entrances of the dignitaries. Mrs. Widener, who, with her guests, had gone into the library by the west door, was at the main door as the procession approached, and as President Lowell reached her side, she handed him the keys to the building.

In the Memorial Rooms the portrait of Harry Widener was unveiled, then remarks delivered by Henry Cabot Lodge and Lowell. The first book placed in the library was the fourth edition (1634) of John Downame's The Christian Warfare Against the Devil World and Flesh, believed at the time (though no longer) to be the only one, of the books bequeathed to the school by John Harvard in 1636, to have survived the burning of Harvard Hall in 1764.

After the ceremony of presentation, the doors were thrown open, and both graduates and undergraduates had an opportunity to see the beauties and utilities of this important university acquisition.[5][26]

(At the ceremony Eleanor Widener met Harvard professor and surgeon Alexander Hamilton Rice, a noted South American explorer; they married less than four months later.)[27][28]

Amenities touted at the building's opening included "telephones, pneumatic tubes, book lifts, book conveyors and passenger elevators";[4] the marble floors were polished using a machine "so simple that any laborer of ordinary intelligence can operate it to advantage [yet it] can do the work of ten men rubbing by hand."[F]

Nonetheless certain deficiencies were noted almost immediately, including a severe inadequacy in toilet facilities, particularly in the stacks.[13]: 59 "There is something rather humiliating", wrote Harvard librarian Archibald Cary Coolidge, "in having to proclaim to the world that we have three hundred stalls in the new library which furnish unequalled opportunity to the scholar and investigator who wishes to come here, but that in order to use these opportunities he must bring his own chair, table and electric lamp." (J. P. Morganm, Jr. eventually supplied the need.)[17]: 109 Faculty competition for the coveted private studies giving direct access to the stacks has at times required significant attention from the school's higher administration.[13]: 72-75

Tunnels from the lowest stack level connect to nearby Pusey Library and Lamont Library.[30] An enclosed bridge connecting to Houghton Library (exiting Widener through one of its windows, and thus respecting Eleanor Widener's "no single brick or stone" admonition) was removed in 2004.[31][32]

Collections

The ninety-unit Harvard Library system,[8]: 361 of which Widener is the anchor, is the only academic library among the world's five "megalibraries"—Widener, the New York Public, the Library of Congress, the Bibliothèque Nationale, and the British Library—making it "unambiguously the greatest university library in the world," according to a Harvard official.[34]

Widener's three and one-half million volumes[8]: 361 occupy 57 miles (92 km) of shelves[35] along four miles of aisles[36] laid out on ten levels of stacks[37]: 4 —a "labyrinth" which one student "could not enter without feeling that she ought to carry a compass, a sandwich, and a whistle." [38][G] (Again alone among the "megalibraries", only Harvard allows patrons the "long-treasured privilege" of entering the stacks to browse as they please, instead of requesting books through library staff.[44] Though until a recent renovation the stacks were "devoid of maps or signs—'There was the expectation that if you were good enough to qualify to get into the stacks you certainly didn't need any help,'" as an official put it[36]—at times color-coded lines and footprints have been applied to the floors for the assistance of the bewildered.)[45][46]

Another one and one-half million volumes are stored offsite in Southborough, Massachusetts.

Harry Elkins Widener Collection

The central Memorial Rooms—an outer chamber housing memorabilia of the life and death of Harry Widener,[citation needed] and an inner library displaying the 3300 rare books collected by him—were described by the Boston Sunday Herald soon after the building's dedication:[47]

The outer of the two rooms is of Alabama marble except the domed ceiling, with fluted columns and Ionic capitals [while the inner room] is finished in carved English oak, the carving having been done in England; the high bookcases are fitted with glass shelves and bronze sashes, the windows are hung with heavy curtains, and in glass-covered cases under them are arranged some examples of the autographed presentation volumes which came to Mr. Widener. Handsome chairs and desk make the furnishings here, and upon the desks are vases filled with flowers. Flowers will always be a part of the furnishings of this room, as the donor ... has arranged that they shall be supplied at regular intervals.

(The Widener family underwrites the Memorial Rooms' upkeep,[48] including weekly renewal of the flowers[49]—originally roses, but now carnations.)[50]

The big marble fireplace and the portrait of Harry Widener occupy a large portion of the south wall. Standing front of the fireplace one may look through the vista made by the doorways, the staircases within and the stairs without and get a glimpse of the green campus.

The same line of sight means that, conversely, "even from the very entrance [of the building] one will catch a glimpse in the distance of the portrait of young Harry Widener on the further wall [of the Memorial Rooms], if the intervening doors happen to be open."[20]: 325 In 1920 the university commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint, within the fourteen-foot-high arched panels flanking the entrance to the Memorial Rooms, two murals giving tribute to the university's World War I dead.[51][H]

The works displayed in the Memorial Rooms comprise Harry Widener's collection at the time of his death—including Shakespeare first folios,[8]: 362 an inscribed copy of Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson, Johnson's own Bible,[48] and works of Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, Thackeray, Charlotte Bronte, Blake and George, Isaac, and Robert Cruikshank—except that the Widener family (only) has the privilege of adding to it. By far the most valuable work in the collection is one of the few perfect copies extant of the Gutenberg Bible,[52] purchased while Harry was abroad by his grandfather Peter A. B. Widener (who intended to surprise Harry with it after the Titanic docked in New York) and donated to the Collection by the Widener family in 1944.[48] (Like all Harvard's valuable books, works in the Widener Collection may be consulted by students or faculty who demonstrate a bona fide research need.)[53][I]

Gutenberg Bible theft

On the night of August 19, 1969 an attempt was made to steal the Gutenberg Bible, valued at $1 million.[54] The would-be thief hid in a lavatory until after closing, then made his way to the roof, from which he descended via a knotted rope to a Memorial Room window, which he broke into. But after smashing the Gutenberg's display case and placing its two volumes in a knapsack, he found it impossible to reclimb the rope carrying the 70-pound (32 kg) booty.[55]

Eventually he fell some 40 feet (12 m)[54] to the pavement where (despite landing on the knapsack)[55] he lay unconscious until discovered and arrested the following morning. "It looks like a professional job all right, in the fact that he came down the rope," commented Harvard Police Chief Robert Tonis. "But it doesn't look very professional that he fell off." Only the books' bindings (which are not original) were damaged.[54]

Since the incident at most one or the other Bible volume is displayed at any given time, with the undisplayed volume secured in the library's vault.[55]

Renovation

A $97 million renovation completed in 2004—the first since the building opened[56]—added fire suppression and environmental control systems, upgraded wiring and communications, enclosed the light courts to create reading rooms, and remodeled various public spaces. "Claustrophobia-inducing" elevators were replaced,[46] the bottom shelves on the lowest stacks level were removed in recognition of chronic seepage problems,[56] Widener's "olfactory nostalgia ... actually the smell of decaying books" was remedied,[57] and unrestricted light and air, seen as desirable when the building was built but now considered "public enemies one and two for the long-term safety of old books", were controlled.[36]

The work was complicated by the terms of Eleanor Elkins Widener's gift—which forbade altering any "single brick or stone" of the exterior, or that "structures of any kind [be] erected in the courts around which the said building is constructed, but that the same shall be kept open for light and air". [17]: 86 [58][13]: 42 The need to relocate each of the building's 3 million volumes—first to temporary locations, then back, as work proceeded aisle by aisle—was turned to advantage, so that by the end of the renovation related materials in the library's two parallel classification systems—the older "Widener" system, and the Library of Congress system. adopted in the 1970s[59]: 256 —were physically adjacent for the first time in one hundred years.[35] The chart showing the floor and wing location, within the stacks, of each subject classification was revised sixty-five times during construction.[36]

The renovation received the 2005 Library Building Award from the American Library Association and the American Institute of Architects,[60] and a 2005 Palladio Award.[61]

Notes

- ^ Excerpted from the remarks of Henry Cabot Lodge at the Library's dedication.[5]

- ^ In 1903 the Harvard Graduates Magazine warned of the desperate need for a new library, Gore Hall having reached capacity decades earlier, forcing much of the collection into dormitory basements: "Only the Congressional Library and the Boston Public Library surpass [Harvard's collection]. But what avails this wealth of material, if it be not properly housed? As well not possess, as to be powerless to use what you possess." Gore was dark, the staff worked under "sweat-shop" conditions, and "open-work iron floors render quiet impossible ... the mud on the boots of the student above drops onto the head of the student below ... Cataloguing falls behind, for there Is not sufficient room to seat the cataloguers."

The situation was exacerbated by Harvard's "generous policy of serving scholars everywhere ... The number of writers and investigators who come to Cambridge to consult its treasures constantly grows ..." And though in an earlier era "the library was used by comparatively few, with the development of the elective system and of higher courses in research, access to books [had become] as indispensable for students in the literary branches as laboratories are to scientific students."

As a result, "other colleges—younger, smaller, less richly endowed—profiting by the methods organized at Harvard, have now outstripped us in capacity for usefulness ... Columbia, Princeton, Cornell, and the University of Wisconsin have now each a million dollar building. We can certainly rejoice for them, but what can we say of ourselves? ... There are throughout the country rich men, looking for fit objects for benefaction. It ought not to be difficult to persuade one of these that in providing a library for Harvard he would be doing a work of national benefit." [10]

- ^ [8]: 362 [16]: 147 Trumbauer was extremely shy, and sensitive about his lack of formal education. "He had literally to be dragged to Cambridge and dressed in his academic gown by Mrs. Widener for the graduation ceremonies in June 1915, when Harvard awarded him his only honorary degree, a master of arts."[15]: 333

- ^ Because a cold prevented Eleanor Widener from attending the groundbreaking, Harry Widener's brother George did the ceremonial digging, the frozen ground softened in advance by a two-day bonfire.[17]: 87

At the cornerstone-laying ceremony Eleanor Widener, using a silver trowel, buried in the cornerstone an inscribed silver tablet; the morning's Boston and New York newspapers; photographs of Harry Widener, Eleanor Widener, and George Dunton Widener; newspapers reporting the February groundbreaking; and United States coins ranging in value from one cent to twenty dollars.[18]

- ^ Sources conflict as to whether the building's style is "Beaux-Arts",[21] "Georgian",[22]: 57 [23]: 457 "Hellenistic",[24]: 281 or "the austere, formalistic Imperial [or 'Imperial and Classical'] style displayed in the Law School's Langdell Hall and the Medical School quadrangle".[8]: 361

- ^ [29] In the basement (now converted to additional shelving as stacks Level D)[citation needed] were the "somewhat elaborate machinery needed for the use of the building—the dynamos which run the five elevators and two book-lifts, the compressed air machinery for the pneumatic tubes, the dynamo and fan for the vacuum-cleaning system, a pump connected with the steam-heating apparatus, enormous fans which pump warm air into the Reading-Room and the stack, a filter through which passes all water which enters the building, and the connections for electric light and power. The building is to be heated by steam, conveyed through a tunnel from the plant of the Elevated Railroad Company, which also furnishes heat to the other buildings of the College Yard and to the freshman dormitories. Such, in brief, is the superb building which Mrs. Widener has erected as a memorial of her son, and which will provide unequalled facilities for the use of books by professors, by students, and by visiting scholars." [20]: 328

- ^ In H. P. Lovecraft's fictional universe Cthulhu Mythos, "a 17th century edition" of the Necronomicon is somewhere in the Widener stacks.[39][40][41][42][43]

- ^ "Six years later[clarification needed] the University published plans [to build what is now known as] Memorial Church to face Widener across the Yard and permanently display the Honor Roll, listing the names of the nearly four hundred Harvard men who perished in the war. This programmatic ensemble, located at the physical center of the University, forms the most elaborate World War I memorial in the Boston area."[51]

- ^ Though still housed in Widener Library's Memorial Rooms, the Harry Elkins Widener Collection is now part of the collection of Houghton Library, Harvard's rare book and manuscript library.[53]

References

- ^ Hanke, Timothy (June 4, 1998). "Counting Libraries at Harvard: Not as Easy as You Think". Harvard University Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "Widener Library Collections. Overview". hcl.harvard.edu. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-23-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "Harry Elkins Widener Collection. Overview". hcl.harvard.edu. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ a b c Library planning, bookstacks and shelving, with contributions from the architects' and librarians' points of view. Snead & Company Iron Works. 1915. pp. 11, 152–8.

- ^ a b "Harvard Commencement. Widener Is Dedicated – Senator Lodge Makes the Speech of Presentation – President Lowell Accepts Gift for Harvard – In presence of Many Distinguished Guests – Mrs. Widener, Donor, Delivers the Keys – Bishop Lawrence in Benediction and Prayer – Exercists are in Library Memorial Room – University Marshal Warren Is in Charge". Boston Evening Transcript. June 24, 1915. p. 2.

- ^ Dienstag, John (May 3, 2004). "Widener Reading Room Reopens". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ "Mrs. A. H. Rice Dies in a Paris Store – New York and Newport Society Woman, Wife of Explorer, Noted for Philanthropy – A Survivor of Titanic – Lost First Husband and Son in Disaster – Gave Library to Harvard University", New York Times, July 14, 1937

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; Shenton, Robert (2004). Harvard A to Z. Harvard University Press.[better source needed]

- ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "The Memorial Library. Will of Harry Elkins Widener". History of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Collection. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "From a Graduate's Window". Harvard Graduates Magazine. 12 (45). Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association: 23–25. September 1903.

- ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "The Memorial Library. The Gift to Harvard". History of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Collection. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon (April 5, 2012). "Widener Library rises from Titanic tragedy". Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Battles, Matthew (2004). Widener: Biography of a Library. Harvard College Library, 2004.

- ^ a b "Julian Abele". Sprinkler Valve Through Door: A peek inside Harvard's Widener Library. February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Baltzell, E. Digby (1996). Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. Transaction Publishers. [better source needed]

- ^ Meister, Maureen (2003). Architecture and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Boston: Harvard's H. Langford Warren.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c Archibald Cary Coolidge and the Harvard Library. Vol. 22. 1974.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "The Memorial Library. The Cornerstone". History of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Collection. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ Fleming, Donald (1986), "Eliot's New Broom", Glimpses of Harvard Past, Harvard University Press, p. 73

- ^ a b c Lane, William Coolidge (May 1915). "The Widener Memorial Library of Harvard College". The Library Journal. 40 (5): 325.

- ^ Scott, Don (September 9, 2013). "Harry Elkins Widener Library on Harvard campus bears a tragic past". Glenside News Globe Times Chronicle. Montgomery Media. Retrieved 2014-05-23.[better source needed]

- ^ Lacock, John Kennedy (1923). Boston and vicinity including Cambridge, Arlington, Lexington, Concord, Quincy, Plymouth, Salem and Marblehead. Historic landmarks and points of interest and how to see them. Boston: Chapple Pub. Co.

- ^ British Universities Encyclopaedia: pt. 1-2. World's libraries and librarians. London: British Universities Encyclopaedia Limited and the Athenaeum Press. 1939.

- ^ Whiffen, Marcus; Koeper, Frederick (1983). American Architecture: 1860-1976.

- ^ Shand-Tucci, Douglas (2001). The Campus Guide: Harvard University. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 165–169. ISBN 9781568982809.

- ^ Tomase, Jennifer (November 1, 2007). "Tale of John Harvard's Surviving Book". Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "The Memorial Library. The Rotunda". History of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Collection. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Explorer Rice Weds Mrs. G. D. Widener – Law Requiring Five Days' Delay After Securing License Waived by a Court Order – Plans for Secrecy Fail – Bishop Lawrence Officiates at Ceremony in Emmanuel Church Vestry Witnessed by Twelve Persons", New York Times, October 7, 1915

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Improved Machinery. An Electric Floor Surfacing Machine". The Engineering Magazine. June 1916. p. iv.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|http://books.google.com/books?id=ignored (help) - ^ Theodore, Elisabeth S. (November 14, 2001). "Widener Beefs Up Security". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ HCL Communications (November 6, 2003). "Houghton bridge is coming down". Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ Seward, Zachary M. (November 18, 2003). "Widener Library Bridge Coming Down". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ "The bookplates of Harvard men". Modern Books and Manuscripts – Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- ^ "Speaking Volumes". Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. February 26, 1998.

- ^ a b Harvard College Library (2009). "HCL News. Widener Stacks Division Completes the Movement of Millions of Volumes – Not an Easy Trick". hcl.harvard.edu. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-23-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d Potier, Beth (September 30, 2004). "Widener Library renovations: On time, on budget". Harvard Gazette.

- ^ Battles, Matthew (2004). Library: An Unquiet History. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara W. Practicing History: Selected essays. p. 15.

- ^ Kelley-Milburn, Deborah (June 1, 2012). "Does Harvard have a copy of the Necronomicon?". Harvard Library. Ask a Librarian. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "History of the Necronomicon". Sprinkler Valve Through Door: A peek inside Harvard's Widener Library. April 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "April Fools". Sprinkler Valve Through Door: A peek inside Harvard's Widener Library. April 2, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bilstad, T. Allan (2009). The Lovecraft Necronomicon primer: a guide to the Cthulhu mythos.

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. (1977). A history of the Necronomicon (2nd ed.).

- ^ Hightower, Marvin (March 28, 1996). "Destroyer of Books Gets Stiff Sentence". Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ "Fifteen Minutes: Blue Line". Harvard Crimson. September 30, 1999.

- ^ a b Gewertz, Ken (Oct. 17, 2002). "Widener's main entrance to close for renovation". Harvard Gazette. The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "The Memorial Library. The Library Opens". History of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Collection. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ a b c Halberstam, David (April 7, 1953). "The Widener Memorial Room". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Kelley-Milburn, Deborah (Oct. 3, 2011). "Is it true that fresh flowers are delievered daily to the Widener Memorial Room?". Harvard Library. Ask a Librarian. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Schaffer, Sarah J. (February 18, 1995). "Bibliophobia". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ a b

- "Sargent's Harvard murals". Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston and the President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2003. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- "Sargent's Harvard Murals. Entering the War".

- ^ Harvard College Library (2009). "Houghton Library. Collections. Harry Elkins Widener Collection. The Gutenberg Bible". hcl.harvard.edu. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ a b Harvard College Library (2014). "Houghton Library. Collections. Harry Elkins Widener Collection. Access". hcl.harvard.edu. The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 2014-23-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c "Burglar Slips as He Tries to Remove Gutenberg Bible From Widener Library", Harvard Crimson, September 18, 1969

- ^ a b c Reed, Christopher (March 1997). "Biblio Klept". Harvard Magazine.

- ^ a b Danuta A. Nitecki; Curtis L. Kendrick, eds. (2001). Library Off-site Shelving: Guide for High-density Facilities. Libraries Unlimited. p. 129.

- ^ Goins, Jason M. (March 23, 1999). "Needed Renovations Planned For Widener". Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Bentinck-Smith, William (1976). Building a great library: the Coolidge years at Harvard. p. 79.

- ^ Wayne A. Wiegand; Donald G. Davis, eds. (1994). Encyclopedia of Library History. Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Library Leadership and Management Association. "Previous Winners of the AIA/ALA Library Buildings Award Program". American Library Association.

- ^ "2005 Palladio Awards". Retrieved 2014-05-22.

External links

- History of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Collection – Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Library buildings completed in 1915

- University and college academic libraries in the United States

- Harvard University buildings

- Libraries in Massachusetts

- Widener family

- Buildings and structures in Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1915 establishments in Massachusetts

- Libraries in Middlesex County, Massachusetts

- Harvard Square

- Harvard Library