Thévenin's theorem

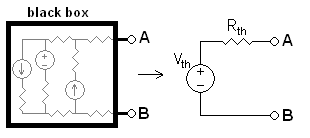

As originally stated in terms of DC resistive circuits only, the Thévenin's theorem holds that:

- Any linear electrical network with voltage and current sources and only resistances can be replaced at terminals A-B by an equivalent voltage source Vth in series connection with an equivalent resistance Rth.

- This equivalent voltage Vth is the voltage obtained at terminals A-B of the network with terminals A-B open circuited.

- This equivalent resistance Rth is the resistance obtained at terminals A-B of the network with all its independent current sources open circuited and all its independent voltage sources short circuited.

In circuit theory terms, the theorem allows any one-port network to be reduced to a single voltage source and a single impedance.

The theorem also applies to frequency domain AC circuits consisting of reactive and resistive impedances.

The theorem was independently derived in 1853 by the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz and in 1883 by Léon Charles Thévenin (1857–1926), an electrical engineer with France's national Postes et Télégraphes telecommunications organization.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Thévenin's theorem and its dual, Norton's theorem, are widely used for circuit analysis simplification and to study circuit's initial-condition and steady-state response.[7][8] Thévenin's theorem can be used to convert any circuit's sources and impedances to a Thévenin equivalent; use of the theorem may in some cases be more convenient than use of Kirchhoff's circuit laws.[6][9]

Calculating the Thévenin equivalent

To calculate the equivalent circuit, the resistance and voltage are needed, so two equations are required. These two equations are usually obtained by using the following steps, but any conditions placed on the terminals of the circuit should also work:

- Calculate the output voltage, VAB, when in open circuit condition (no load resistor—meaning infinite resistance). This is VTh.

- Calculate the output current, IAB, when the output terminals are short circuited (load resistance is 0). RTh equals VTh divided by this IAB.

The equivalent circuit is a voltage source with voltage VTh in series with a resistance RTh.

Step 2 could also be thought of as:

- 2a. Replace the independent voltage sources with short circuits, and independent current sources with open circuits.

- 2b. Calculate the resistance between terminals A and B. This is RTh.

The Thévenin-equivalent voltage is the voltage at the output terminals of the original circuit. When calculating a Thévenin-equivalent voltage, the voltage divider principle is often useful, by declaring one terminal to be Vout and the other terminal to be at the ground point.

The Thévenin-equivalent resistance is the resistance measured across points A and B "looking back" into the circuit. It is important to first replace all voltage- and current-sources with their internal resistances. For an ideal voltage source, this means replace the voltage source with a short circuit. For an ideal current source, this means replace the current source with an open circuit. Resistance can then be calculated across the terminals using the formulae for series and parallel circuits. This method is valid only for circuits with independent sources. If there are dependent sources in the circuit, another method must be used such as connecting a test source across A and B and calculating the voltage across or current through the test source.

Example

|

|

|

|

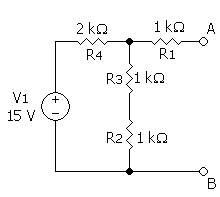

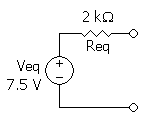

In the example, calculating the equivalent voltage:

(notice that R1 is not taken into consideration, as above calculations are done in an open circuit condition between A and B, therefore no current flows through this part, which means there is no current through R1 and therefore no voltage drop along this part)

Calculating equivalent resistance:

Conversion to a Norton equivalent

A Norton equivalent circuit is related to the Thévenin equivalent by the following:

Practical limitations

- Many circuits are only linear over a certain range of values, thus the Thévenin equivalent is valid only within this linear range.

- The Thévenin equivalent has an equivalent I–V characteristic only from the point of view of the load.

- The power dissipation of the Thévenin equivalent is not necessarily identical to the power dissipation of the real system. However, the power dissipated by an external resistor between the two output terminals is the same regardless of how the internal circuit is implemented.

A proof of the theorem

The proof involves two steps. First use superposition theorem to construct a solution, and then use uniqueness theorem to show the solution is unique. The second step is usually implied. Firstly, using the superposition theorem, in general for any linear "black box" circuit which contains voltage sources and resistors, one can always write down its voltage as a linear function of the corresponding current as follows

where the first term reflects the linear summation of contributions from each voltage source, while the second term measures the contribution from all the resistors. The above argument is due to the fact that the voltage of the black box for a given current is identical to the linear superposition of the solutions of the following problems: (1) to leave the black box open circuited but activate individual voltage source one at a time and, (2) to short circuit all the voltage sources but feed the circuit with a certain ideal voltage source so that the resulting current exactly reads (or an ideal current source of current ). Once the above expression is established, it is straightforward to show that and are the single voltage source and the single series resistor in question.

See also

- Millman's theorem

- Source transformation

- Superposition theorem

- Norton's theorem

- Maximum power transfer theorem

- Extra element theorem

References

Bibliography

- Brenner, Egon (1959). "Chapter 12 - Network Functions". Analysis of Electric Circuits. McGraw-Hill. pp. 268–269.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Brittain, J.E. (March 1990). "Thevenin's theorem". IEEE Spectrum. 27 (3): 42. doi:10.1109/6.48845. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Dorf, Richard C.; Svoboda, James A. (2010). "Chapter 5 - Circuit Theorems". Introduction to Electric Circuits (8th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 162–207. ISBN 978-0-470-52157-1.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - Dwight, Herbert B. (1949). "Sec. 2 - Electric and Magnetic Circuits". In Knowlton, A.E. (ed.). Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 26.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - Elgerd, Olle I. (2007). "Chapter 10, Energy System Transients - Surge Phenomena and Symmetrical Fault Analysis". Electric Energy Systems Theory: An Introduction. Tata McGraw-Hill. pp. 402–429. ISBN 978-0070192300.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - Helmhotz, H. (1853). "Über einige Gesetze der Vertheilung elektrischer Ströme in körperlichen Leitern mit Anwendung auf die thierisch-elektrischen Versuche (Some laws concerning the distribution of electrical currents in conductors with applications to experiments on animal electricity)". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 89 (6): 211–233.

- Johnson, D.H. (2003a). "Origins of the equivalent circuit concept: the voltage-source equivalent" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 91 (4): 636–640. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2003.811716.

- Johnson, D.H. (2003b). "Origins of the equivalent circuit concept: the current-source equivalent" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 91 (5): 817–821. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2003.811795.

- Thévenin, L. (1883a). "Extension de la loi d'Ohm aux circuits électromoteurs complexes (Extension of Ohm's law to complex electromotive circuits)". Annales Télégraphiques. 3e series. 10: 222–224.

- Thévenin, L. (1883b). "Sur un nouveau théorème d'électricité dynamique (On a new theorem of dynamic electricity)". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 97: 159–161.

- Wenner, F. (1926). "Sci. Paper S531, A principle governing the distribution of current in systems of linear conductors". Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Standards.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- First-Order Filters: Shortcut via Thévenin Equivalent Source — showing on p. 4 complex circuit's Thévenin's theorem simplication to first-order low-pass filter and associated voltage divider, time constant and gain.

- Thevenin’s Theorem. Easy Step by Step Procedure with Example

![{\displaystyle R_{\mathrm {Th} }=R_{1}+\left[\left(R_{2}+R_{3}\right)\|R_{4}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/59b9f708bc93f67950d3ba9acc945685cc273d4c)

![{\displaystyle =1\,\mathrm {k} \Omega +\left[\left(1\,\mathrm {k} \Omega +1\,\mathrm {k} \Omega \right)\|2\,\mathrm {k} \Omega \right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88305e6af8f126727745786cc21ac95e058b11e0)