Irataba

Irataba | |

|---|---|

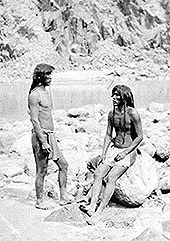

February 1864 (artist's rendering) | |

| Mohave leader | |

| Preceded by | Cairook |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1814 Arizona |

| Died | May 1874 Colorado River Indian Reservation |

| Cause of death | Uncertain |

| Known for | Irataba was the last independent chief of the Mohave. |

Irataba (also known as Yara tav, from eecheeyara tav; c. 1814 – 1874), was the last independent chief of the Mohave Nation of Native Americans. He was born c. 1814 near the Colorado River in present-day Arizona.

As a youth, Irataba dreamed that the Mohave would experience a great change, and he would one day become their chief. The first part of his vision began to materialize in 1849, when he and Chief Cairook encountered a large group of European Americans, including Captain Amiel Whipple and Lieutenant J.C. Ives, who were leading an exploratory expedition up the Colorado River. The second part of his vision was realized in 1859, when, following Cairook's death in captivity, he was made principle chief of the Mohave Nation.

In 1858, Irataba and the Mohave perpetrated a massacre against the Rose-Baley Party, the first European American emigrant wagon train to traverse the 35th parallel route known as Beale's Wagon Road, established by Edward Fitzgerald Beale, from Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico to the Colorado River near present-day Needles, California. This elicited a swift response from the US War Department, who in April 1859 established Fort Mohave near the site of the massacre to protect white travelers.

In 1864, Irataba traveled to Washington, D.C. for an official visit with members of the United States military and its government, including President Abraham Lincoln. During his stay he toured the US capital, New York City, and Philadelphia, and enjoyed great acclaim along the way; Americans lavished him with gifts of medals, swords, and photographs, and Lincoln gave him a silver-headed cane. When the tour ended, he returned home to report what he had seen, but the Mohave did not believe his story, and they subsequently mocked him mercilessly. He died ten years later in relative disgrace, though his tribe had accepted that his vision became reality. The Mohave never replaced Irataba as head chief; he was their last, and was given full traditional respect upon his death in 1874.

Early life and vision

Irataba or Yara tav, from the Mohave eecheeyara tav, meaning "beautiful bird", also rendered as Irateba, Arateve, and Yiratewa, was born into the Neolge, or Sun Fire clan of Mohave Native Americans c. 1814.[1] He was raised in present-day Arizona, near the Nevada and California border, on the east bank of the Colorado River in the Mohave Valley and in the shadow of a group of sharply pointed rocks known as the Needles, located south of where the Grand Canyon empties into the Mohave Canyon. The Mohave Desert stretches for miles to the west, but as a child he did not venture into the unforgiving wilderness.[2]

Irataba excelled at archery, hunting game such as rabbits and deer in the mountains to the east.[2] In the spring, when the volume of the Colorado River was increased by snowmelt from neighboring mountains, flooding the bottomlands, he helped his tribe cultivate corn, watermelons, beans, gourds, tobacco, and pumpkins.[3] In an effort to alleviate the intense heat of summer, he covered his body with river mud, which also helped to keep insects away, and conserved energy by resting in a thatched hut made from willow branches known as a ramada.[2][nb 1]

The Mohave people hold dreams, or visions, in high regard, and Irataba is known in their culture for having had an important one that is also considered their people's "saddest".[2] One night, while still a youth, he dreamed that he would one day become chief of the Mohave, and that this period would be marked by what the Dream Person described as, "new things and strange things that no other Mohave" had experienced.[2] Irataba was instructed that he should "never be afraid of them", for only in this way could he "become a mighty chief".[5]

Adulthood

[Irataba] is a big Indian, literally as well as figuratively ... granitic in appearance as one of the Lower Coast mountains, with a head only less in size to a buffalo's and a lower jar massive enough to crush nuts or crush quartz.

—Daily Evening Bulletin, December 2, 1863

According to author Frank Waters, Mohave men were extraordinary in stature, with Chief Cairook reaching a barefoot height of nearly six and a half feet. By adulthood, Irataba had grown almost as tall as Cairook, becoming "his most trusted sub-chief".[5][nb 2]

The Mohave were fierce warriors who often battled against the Chemehuevi, a neighboring tribe that regularly made trips up the Colorado River to pillage the Mohave's food stores.[5] They were also in frequent conflict with several tribes of the Colorado Plateau, including the Paiute, Hualapai, Yavapai, and Havasupai peoples. Irataba accompanied Mohave war parties as a bowman tasked with inflicting damage on an approaching group and keeping them "at bay", in preparation for melee attacks by warriors brandishing war clubs capable of crushing their opponent's skulls "like ripe pumpkins".[5] They considered themselves "masters" of the Colorado River, victoriously shouting Ahotka, which means good or great, as their frightened enemies retreated in haste.[5]

Contact with European Americans

In 1849, Irataba, Cairook, and the Mohave people encountered a large group of European Americans, including Captain Amiel Whipple and Lieutenant J.C. Ives, who were leading an exploratory expedition up the Colorado River.[7] The party included horses, mules, and wagons that the Mohave perceived as the "new and strange things" that Irataba's dream had foretold many years earlier.[5] The group's interpreter informed the Mohave that they needed help crossing the river, and Irataba and others obliged, first swimming a rope across with which they towed the party's packs on rubber pontoons before driving the wagons, horses, and mules to the opposite bank.[8]

The survey party then asked the Mohave to guide them across the desert, promising gifts in exchange for their services. Cairook and Irataba agreed, and they escorted the group across the hostile territory of the Paiute to the Old Spanish Trail that would take them to southern California. When they parted ways, Ives thanked Irataba and promised to remember how he had "been a great help to [the] white people".[8][nb 3]

In October 1857, the Mohave encountered an expedition led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale that was tasked with establishing a trade route along the 35th parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas to Los Angeles.[10] The wagon trail began at Fort Smith and continued through Fort Defiance, Arizona before crossing the Colorado River.[9] Once again, Irataba helped the European Americans, and Beale named the location where they crossed the river, en route to California, Beale's Crossing.[8]

In February 1858, a lookout stationed high on a cliff in the Mohave Canyon alerted the tribe to a "preposterous sight", a paddle steamer spewing black smoke and blowing a shrill air whistle.[11] When the boat stopped and several white men came ashore trading plant seeds and beads for corn and beans, Irataba realized that their leader was Lieutenant Ives, who had several years earlier promised to remember him.[12] Ives was leading an expedition to the Grand Canyon in a steamship named the Explorer, and he asked Cairook and Irataba to join them as guides.[13] Though the "Big Canyon" was considered "mysterious" and the territory of the Hualapais, Cairook and Irataba agreed and invited a Mohave boy named Nahvahroopa to join them.[14][nb 4]

Exploring the Grand Canyon

Irataba guided the party from the Explorer's deck, indicating the location of sandbars and rapids and advising the ship's pilot regarding convenient places to anchor while resting for a night. As the expedition progressed, the rapids grew in strength and intensity, and the rock walls increasingly towered above them. When they reached the entrance to the Black Canyon of the Colorado, the Explorer crashed against a submerged rock, throwing several men overboard, dislodging the ship's boiler, and severely damaging its wheelhouse. Ives implored, "take to the skiff before she sinks."[16]

The crew quickly set up camp on shore, but immediately realized that they had salvaged only a small portion of their corn and bean supply. Irataba volunteered to go back and secure more food, warning that the expedition was being watched by Paiutes. When he returned several days later with a pack train carrying provisions, he remembered that the Dream Person had instructed him "to be afraid of nothing", and so he continued with the group into the unknown wilderness of the Grand Canyon.[8] There they encountered several friendly Hualapais who agreed to guide them east toward Fort Defiance.[12] Irataba was reluctant to venture deeper into the canyon, concerned that the party would get ambushed by Native Americans aligned with Mormons, as he advised: "many whites live with the Paiutes".[17][nb 5] And so, with his services no longer needed, he returned home to the Mohave villages.[12]

Turning point

Upon his return, Irataba found Chief Cairook uneasy about his tribe's willingness to help the white explorers, who he distrusted. Cairook's apprehension had been building for several months, and he decided to call a meeting of his sub-chiefs to discuss the situation. He expressed concern that many white men were coming from both the south and east, and because their paths intersected in the Mohave's ancestral homeland, "our peace is broken. What shall we do being masters of the Colorado?"[19]

Cairook declared that the next time whites came through the region the Mohave would endeavor to stop repel them.[19] He believed that the "signs" supported his decision, and he instructed the tribe's medicine men, the hota, to make stone circles on the routes that the white men used to magically impede their progress. He also spoke of a recent dream that featured a "great star of fire, with a blazing tail. It is a star of war, a star of blood. What do you say?"[19] Irataba, who was sympathetic to the whites, said nothing, but he understood well what the unspoken consensus meant for the tribe's future relations with European Americans.[19]

Rose-Baley Party massacre

In 1858, a wealthy farmer from Iowa, Leonard John Rose, formed a large emigrant wagon train after having sold most of his property in Iowa, amassing what was then a small fortune of $30,000, which enabled him to purchase an animal stock that included two dozen horses and two hundred head of red Durham cattle. The Rose party left Iowa in early April and were joined by the Baley family while traveling through Kansas in May.[20][nb 6] They reached Albuquerque, New Mexico on June 23, where several more families and their livestock joined them before traveling to the Colorado River by way of Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico, where they would become the first emigrant train to venture onto Beale's Wagon Road.[22][nb 7]

On August 27, the emigrants reached the Black Mountains and made their crossing at Sitgreaves Pass, elevation 3,652 feet.[24][nb 8] From the crest they could see the Colorado River in the distance, but having worked continuously during the morning and afternoon, they stopped to prepare their first meal of the day. While they were cooking, a small group of Mohave approached and asked, in a combination of broken English and Spanish, how many people the wagon train included and whether they intended to settle near the Colorado River. They told the Mohave that they were traveling through the region on their way to California, which seemed to appease them, many of whom helped the party during their decent to the Colorado.[25]

Around midnight, the Baley company, who had fallen behind the others, decided to stop and make a mountain camp while the Rose company continued to the Colorado, where they planned to water the train's combined stock and build a raft in preparation for the impending river crossing. There the emigrants encountered more Mohave, but unlike the friendly ones that greeted them at Sitgreaves Pass, these were decidedly unwelcoming.[26] Several people were physically harassed, and many of the party's cattle were driven away and slaughtered. The group settled-in for the night at a spot two hundred yards from the river and ten miles from the Baley company's mountain camp.[27] The following morning they moved closer to the river bank, where they could more easily water their stock. Soon afterward, they were visited by Mohave warriors asking about their intentions in the region, including a sub-chief who heard their complaints and assured them that no further depravations would occur.[28] The party sensed that the chief was feigning enthusiasm, but continued to labor.[29] Around noon, they moved closer to where they planned to cross, near a patch of cottonwood trees that were suitable for building rafts.[28]

Around 2 p.m. on August 30, the emigrants working near the river were attacked by approximately three hundred Mohave warriors, who let out terrifying "war whoops" as they sent arrows flying into the camp.[30] The men quickly armed themselves as women frantically fled with their young ones to the protection offered by the covered wagons.[31] The onslaught continued for several hours, but Rose and others held off the assailants, who eventually retreated.[32] In all, eight members of the Rose-Baley Party had been killed, including five children, and twelve wounded; of the train's livestock, only seventeen cattle and ten mules and horses remained.[33] The emigrants managed to kill seventeen Mohave warriors.[34] With the wounded in one wagon, the children in another, and the healthy adults on foot, the party began their "torturous" five hundred-mile journey back to Albuquerque, during which they observed "a great star on fire, racing across the dark sky with a blazing trail".[35] According to historian A.L. Kroeber, "the event sealed the fate of the Mohave as an independent people."[29]

Fort Mohave

When news of the massacre reached the west, the US War Department decided to establish a military fort at Beale's Crossing to protect white travelers, and on December 26, 1858, Colonel William Hoffman and fifty dragoons were dispatched from Fort Tejon to cross the desert and confront the Mohave.[36] Irataba attempted to arrange a peaceful meeting, but Hoffman ordered his troops to fire on the warriors, who attacked and repelled the force.[37] Hoffman returned in April 1859, by way of Fort Yuma, with seven companies of infantry and four hundred pack animals.[38] When they arrived at Beale's Crossing, which was still littered with wagon parts and human bones, three hundred Mohave warriors were waiting for them, but were reluctant to attack the imposing army of five hundred soldiers.[39] Hoffman arranged for a meeting between he and his officers and Cairook and his sub-chiefs, with a Yuman "head man", Pascual, translating from English to Spanish to Yuman and Mohave and vice versa.[40]

Hoffman demanded that the Mohave agree to never again harm white settlers along the wagon trail, and he ordered that a fort be built at Beale's Crossing to enforce the decree. When he asked which chief had ordered the attack on the Rose-Baley Party, Cairook proudly admitted: "It was I."[41] Hoffman then declared that, as punishment, the Mohave were required to surrender three warriors who had taken part in the massacre and six prominent leaders. Cairook offered himself as a hostage, and he and the others were transported in the river steamer, General Jessup, to Fort Yuma.[40] Many soldiers remained to begin construction on Fort Mohave.[41] After its completion, Irataba and five to eight hundred of his most ardent supporters moved to the Colorado River Valley, where in 1865 the Colorado River Indian Reservation was established.[42] This marked the beginning of a rift between two rival factions of Mohave, the other led by a respected sub-chief named Homoseh quahote, known by the whites as Seck-a-hoot.[43]

Death of Cairook

In June 1859, one of the men taken prisoner by the US Army escaped and made his way back to the Mohave. He informed Irataba that Cairook had been killed by a soldier while trying escape the miserable conditions of the prison, which amounted to a small hut that left them exposed to the desert's harsh elements. As word of the chief's death spread throughout the village, people began to gather at Irataba's ramada. A tribal spokesman told him that, in keeping with Mohave tradition, Cairook's hut and belongings had been burned, and that he was now their rightful leader; Irataba agreed, stating: "It is as I dreamed. I will be your chief."[41] Thus Irataba became the Mohave's head chief, known as an Aha macave yaltanack or hochoch, which designated him as the leader made, or elected, by the people.[44]

With an army of Mohave warriors in his command, Irataba quickly earned a reputation for just leadership, and Americans in the region respectfully referred to him as "Chief of the Mohaves, the great tribe of the Colorado Valley".[45] In 1862, Irataba acted as a guide for the Walker Party Exploration, led by Joseph R. Walker and including Jack Swilling, who would later found Phoenix, Arizona. They came in search of gold and were brought to a river that Irataba called Hasyamp, later officially named Hassayampa River, where they found plentiful amounts of the precious metal. Arizona's first mining district was established there the following year, which led to the founding of Prescott, Arizona soon afterward.[46] During this period, relations between the Mohave and European Americans were positive; however, as white emigration increased, gold seekers founded a town nearby named La Paz, stirring tensions among the Mohave and building fear of an uprising against further encroachment on their land. Longtime guide and scout John Moss remarked, "Irataba's influence is keeping peace along the river and is of more value than a regiment of soldiers ... Let's take him to Washington and impress upon him the numbers and strength of the white man."[47] Irataba agreed to go, and Moss arranged the trip.[47]

Trip to Washington D.C.

In November 1863, Irataba traveled with Moss to San Pedro, Los Angeles, where they boarded a steamship named the Senator, bound for San Francisco.[48] The Mohave Chief had been dressed in a "civilized costume" that included a black suit and white sombrero, and was subsequently met with great exaltation.[47]

In January 1864, they sailed for New York City, by way of the Isthmus of Panama, on the Orizaba.[49] Here Irataba traded his suit and sombrero for the uniform and regalia of a major general, including a bright yellow sash and gold badge encrusted with precious stones. From it hung a medal that bore the inscription, "Irataba, Chief of the Mohaves, Arizona Territory".[47] In February, when The New York Times asked him to explain the nature of his visit, he replied: "to see where so many pale faces come from".[50] That same month, Harper's Weekly described him as, "the finest specimen of unadulterated aboriginal on this continent".[51] When journalist John Penn Curry asked him what he thought of Americans, Irataba replied: "Mericanos too much talk, too much eat, too much drink; no work, no raise pumpkins, corn, watermelons – all time walk, talk, drink – no good."[52] He toured New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., and earned great acclaim at each stop; government officials and military officers lavished him with gifts of medals, swords, and photographs.[47] While in Washington, Irataba met with President Abraham Lincoln, who gave him a silver-headed cane "as a symbol of his chieftainship".[53] He was the first Native American from the Southwestern United States to meet a US president.[6] The tour ended in April, when he and Moss sailed to California, again by way of the Isthmus of Panama, and made their way back to Beale's Crossing, from Los Angeles, in a wagon.[54]

Disgrace and death

Having returned from his trip to Washington, Irataba met with the Mohave dressed in his major general's uniform, which was by now covered in medals. He wore a European-style hat and carried a long Japanese sword that was given to him during his visit. He told the tribe about his incredible journey and all the "new and strange things" he had seen, including the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, steam locomotives, granite skyscrapers that rivaled in height even the towering walls of the Mohave Canyon, and a seemingly endless population of white people.[55] "So did my Great Dream foretell," he declared. "Now it has come true. With my own eyes I have seen it."[56] He tried to convince the Mohave that peace with European Americans was in their best interests, and that war against them was futile, stressing their obviously dominant military capabilities.[57] Nevertheless, the Mohave did not believe what they had heard, and they mocked him and accused him of being the "biggest liar on the Colorado".[56]

The old man is here now with his tribe, but he looks feeble, wan, and grief stricken. Age has come to Irataba, but it has brought to him no bright and peaceful twilight. Dark and cheerless appear the skies of his declining years.[58]

—The Arizona Weekly Miner, February 5, 1870

Although Irataba had fallen out of favor with his people, he continued to lead them in their ongoing conflicts with neighboring tribes.[56] In March 1865, he helped defeat the Chemehuevi in response to their allies, the Paiutes, having killed two Mohave women in retaliation for the Mohave's killing of a Paiute medicine man after he failed to heal nine Mohave people inflicted with small pox.[59] Irataba attacked the Chemehuevi first because they had disrespected the Mohave, and to avoid "a fire in the rear" when he turned their attention to the Paiutes, who were planning an attack on the Mohave farm and granary on Cottonwood Island.[60] During a subsequent battle with the Paiutes, Irataba was taken prisoner while wearing his major general's uniform. They feared that killing him would invite repercussions from the soldiers stationed at Fort Mohave, so they instead stripped him naked and sent him home bloody and battered, to which the Mohave responded with still more ridicule, joking: "Not even the Paiutes would kill him."[56][nb 9]

A particularly strong rift developed between Irataba, who was sympathetic to white settlement, and the militant Mohave sub-chief, Homoseh Quahote, also known as Seck-a-hoot, who vehemently opposed white encroachment on Mohave lands.[61] At one time, Seck-a-hoot briefly imprisoned Irataba in an effort to supplant him as head chief.[57] Ashamed and disgraced, Irataba scorned Native and European Americans alike, and retired in near isolation to a small hut where he lived out his final days. As time went on the people softened in their disdain for him, and as more and more whites settled in their lands it became clear that his dream had indeed come true, but it had also betrayed them. The Mohave never replaced Irataba; he was their last independent head chief, and when he died at the Colorado River Indian Reservation in May 1874, they burned his body, hut, and belongings according to tradition, "as was proper" for a Mohave head chief.[62][nb 10]

References

- ^ Ricky 1999, p. 100: born c. 1814 to the Sun Fire clan; Sherer 1966, p. 6: Irataba's Mohave name was Yara tav, a shortened form of the Mohave eecheeyara tav, but it has also been rendered as Irateba, Arateve, and Yiratewa.

- ^ a b c d e Waters 1993, p. 125.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 125: the Colorado River was increased by snowmelt from neighboring mountains; Wilson 2000, p. 218: the Mohave cultivated corn, watermelons, beans, gourds, tobacco, and pumpkins.

- ^ NYT & May 1864, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Waters 1993, p. 126.

- ^ a b Harte 1886, p. 492.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d Waters 1993, p. 127.

- ^ a b Ricky 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 24–6.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 127: "preposterous sight"; Woodward 1953, p. 54: Irataba and Cairook encountered the crew of the Explorer in February 1858.

- ^ a b c Waters 1993, p. 127–28. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEWaters1993127–28" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Woodward 1953, pp. 54–5.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 128: the "Big Canyon" was considered "mysterious" and the territory of the Hualapais; Woodward 1953, p. 55: Cairook and Irataba agreed to guide the party.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 55.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Zappia 2014, pp. 121, 138.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 4, 14, 28, 131–32.

- ^ a b c d Waters 1993, p. 129.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 2–3, 5, 15.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 24, 28–37, 39–40.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 30–4.

- ^ a b Baley 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 61–2.

- ^ a b Baley 2002, pp. 63–4.

- ^ a b Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 53.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 67–9.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 130.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 70–2.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 68, 71.

- ^ Zappia 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Baley 2002, p. 72: the distance from their camp to Albuquerque was five hundred miles; Waters 1993, p. 130: "a great star on fire, racing across the dark sky with a blazing trail".

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 58.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 63: Irataba attempted to arrange a peaceful meeting; Woodward 1953, p. 58: the Mohave attacked and repelled the force.

- ^ Waters 1993, pp. 130–31.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 130: Beale's Crossing was still littered with wagon parts and human bones; Woodward 1953, p. 58: Hoffman commanded five hundred infantry.

- ^ a b Woodward 1953, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Waters 1993, p. 131.

- ^ Griffin-Pierce 2000, p. 246: Irataba moved to the Colorado River Valley, where in 1865 the Colorado River Indian Reservation was established; Sherer 1966, p. 8: Irataba relocated with five to eight hundred of his most ardent supporters.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 5–6.

- ^ NYT & February 1864: 9,000 warriors in his command; Waters 1993, p. 132: "Chief of the Mohaves, the great tribe of the Colorado Valley".

- ^ Hanchett 1998, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Waters 1993, p. 132.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 61.

- ^ O'Brien 2006, p. 249: sailed by way of the Isthmus of Panama; Waters 1993, p. 132: sailed on the Orizaba.

- ^ NYT & February 1864.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 53.

- ^ Curry 1865, p. 360.

- ^ Ricky 1999, pp. 101–02.

- ^ Woodward 1953, pp. 62–3.

- ^ Waters 1993, pp. 132–33.

- ^ a b c d Waters 1993, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Ricky 1999, p. 102.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 67.

- ^ Woodward 1953, pp. 64–5.

- ^ a b Daily Alta California 1865.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 9, 30.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 8: Irataba died at the Colorado River Indian Reservation; Waters 1993, pp. 133–34: the Mohave never replaced Irataba; Devereux 1951, p. 34: Irataba was the last independent Mohave head chief; Woodward 1953, p. 67: Arizona press reported that Irataba died on May 3 or 4, 1874.

Notes

- ^ Mohave who enjoyed higher status would cover their body in "goose grease" instead of mud.[4]

- ^ Irataba's height was approximately 6'4".[6]

- ^ In 1851, Irataba assisted Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves during his exploration of the Colorado River.[9]

- ^ After two days, Cairook departed and returned home.[15]

- ^ Tensions between Mormons and European American emigrants reached their zenith during 1857–58, with several hostile encounters collectively known as the Mormon War.[18]

- ^ The combined Rose-Baley Party traveled with twenty wagons and numbered forty men, fifty to sixty women and children, and five hundred head of cattle.[21]

- ^ At the insistence of US Army officers stationed in Albuquerque, the Rose-Baley Party was accompanied by Jose Manuel Savedra, a Mexican guide who had traveled with Beale during his initial survey of the route, and his interpreter, Petro.[23]

- ^ The pass was named after Lieutenant Lorenzo Sitgreaves, who led an expedition party to the region in 1851.[24]

- ^ The Paiutes gave Irataba's major general's uniform to his Mohave rival, Seck-a-hoot.[60]

- ^ Irataba's cause of death is unknown, but old age and smallpox are both cited as possible causes.[57]

Bibliography

- Baley, Charles W. (2002). Disaster at the Colorado: Beale's Wagon Road and the First Emigrant Party. Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-0874214376.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curry, John Penn (1865). "Gazlay's Pacific Monthly, Volume 1". The New York Public Library. D. M. Gazlay.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Latest from Irataba's Land". Daily Alta California. Vol. 17, no. 5707. California Digital Newspaper Collection (CDNC). October 22, 1865. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- Devereux, George (1951). "Mohave Chieftainship in Action: A Narrative of the First Contacts of the Mohave Indians with the United States". Plateau. 23 (3). Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art; Museum of Northern Arizona.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Griffin-Pierce, Trudy (2000). Native Peoples of the Southwest. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826319081.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hanchett, Leland J. (1998). Catch the Stage to Phoenix. Pine Rim Publishing LLC. ISBN 9780963778567.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harte, Brett, ed. (1886). Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine. A. Roman.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kroeber, A.L.; Kroeber, C.B. (1973). A Mohave War Reminiscence, 1854-1880. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486281636.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Arrival of the Indian Warrior, Irataba". The New York Times. February 7, 1864. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "Return of Irataba: What he Thinks of New-York". The New York Times. May 4, 1864. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- O'Brien, Anne Hughes (2006). Traveling Indian Arizona. Big Earth Publishing. ISBN 9781565795181.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ricky, Donald B. (1999). Indians of Arizona: Past and Present. North American Book Distributors. ISBN 9780403098637.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sherer, Lorraine M. (March 1966). "Great Chieftains of the Mojave Indians". Southern California Quarterly. 48 (1). University of California Press.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waters, Frank (1993). Brave Are My People: Indian Heros Not Forgotten. Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 9780940666214.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, James (2000). The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0802136800.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Woodward, Arthur (January 1953). "Irataba: Chief of the Mohave". Plateau. 25 (3). Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art; Museum of Northern Arizona.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Zappia, Natale A. (2014). Traders and Raiders: The Indigenous World of the Colorado Basin, 1540-1859. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469615851.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Brown, Dee (2007) [1970]. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Holt McDougal. ISBN 978-0805086843.

- Deloria, Vine (2003) [1973]. God Is Red: A Native View of Religion. Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 978-1555914981.

- Wiget, Andrew, ed. (1996). Handbook of Native American Literature. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780815325864.

- Woodward, Arthur (2012). Feud on the Colorado: Great West And Indian Series, No. 4. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1258430160.

External links

- Official Mohave Nation Website

- Page about the Mohave Reservation by NAU

- Fort Mohave Tribe, InterTribal Council of Arizona