Fractal

The word fractal has two related meanings. In colloquial usage, it denotes a shape that is recursively constructed or self-similar, that is, a shape that appears similar at all scales of magnification and is therefore often referred to as "infinitely complex." In mathematics a fractal is a geometric object that satisfies a specific technical condition, namely having a Hausdorff dimension greater than its topological dimension. The term fractal was coined in 1975 by Benoît Mandelbrot, from the Latin fractus, meaning "broken" or "fractured."

History

Objects that are now called fractals were discovered and explored long before the word was coined. Ethnomathematics like Ron Eglash's African Fractals (ISBN 0-8135-2613-2) documents pervasive fractal geometry in indigeneous African craft. In 1525, the German Artist Albrecht Dürer published The Painter's Manual, in which one section is on "Tile Patterns formed by Pentagons." The Dürer's Pentagon largely resembled the Sierpinski carpet, but based on pentagons instead of squares.

The idea of "recursive self-similarity" was originally developed by the philosopher Leibniz and he even worked out many of the details. In 1872, Karl Weierstrass found an example of a function with the nonintuitive property that it is everywhere continuous but nowhere differentiable — the graph of this function would now be called a fractal. In 1904, Helge von Koch, dissatisfied with Weierstrass's very abstract and analytic definition, gave a more geometric definition of a similar function, which is now called the Koch snowflake. The idea of self-similar curves was taken further by Paul Pierre Lévy who, in his 1938 paper Plane or Space Curves and Surfaces Consisting of Parts Similar to the Whole, described a new fractal curve, the Lévy C curve.

Georg Cantor gave examples of subsets of the real line with unusual properties — these Cantor sets are also now recognised as fractals. Iterated functions in the complex plane had been investigated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Henri Poincaré, Felix Klein, Pierre Fatou, and Gaston Julia. However, without the aid of modern computer graphics, they lacked the means to visualize the beauty of many of the objects that they had discovered.

In the 1960s, Benoît Mandelbrot started investigating self-similarity in papers such as How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension. This built on earlier work by Lewis Fry Richardson. In 1975, Mandelbrot coined the word fractal to denote an object whose Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension is greater than its topological dimension. (Please refer to the articles on these terms for precise definitions.) He illustrated this mathematical definition with striking computer-constructed visualizations. These images captured the popular imagination; many of them were based on recursion, leading to the popular meaning of the term "fractal".

Examples

A relatively simple class of examples is the Cantor sets, in which short and then shorter (open) intervals are struck out of the unit interval [0, 1], leaving a set that might (or might not) actually be self-similar under enlargement, and might (or might not) have a Hausdorff dimension d such that 0 < d < 1. A simple recipe, such as excluding the digit 7 from decimal representations, is self-similar under 10-fold enlargement, and also has Hausdorff dimension log 9/log 10 (this value is the same, no matter what logarithmic base is chosen), showing the connection of the two concepts. By comparison the topological dimension of any Cantor set is 0 and hence all Cantor sets are fractals.

Additional examples of fractals include the Lyapunov fractal, Sierpinski triangle and carpet, Menger sponge, dragon curve, space-filling curve, limit sets of Kleinian groups, and the Koch curve. Fractals can be deterministic or stochastic (i.e. non-deterministic).

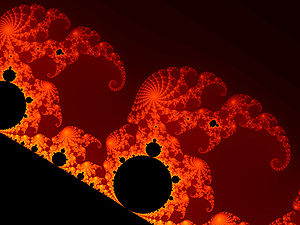

Chaotic dynamical systems are sometimes associated with fractals. Objects in the phase space of a dynamical system can be fractals (see attractor). Objects in the parameter space for a family of systems may be fractal as well. An interesting example is the Mandelbrot set. This set contains whole discs, so it has a Hausdorff dimension equal to its topological dimension of 2 and is not technically fractal—but what is truly surprising is that the boundary of the Mandelbrot set also has a Hausdorff dimension of 2 (in comparison to a topological dimension of 1). (M. Shishikura proved that in 1991.)

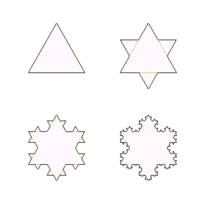

The fractional dimension of the boundary of the Koch snowflake

The following analysis of the Koch Snowflake suggests how self-similarity can be used to analyze fractal properties.

The total length of a number, N, of small steps, L, is the product NL. Applied to the boundary of the Koch snowflake this gives a boundless length as L approaches zero. But this distinction is not satisfactory, as different Koch snowflakes do have different sizes. A solution is to measure, not in meter, m, nor in square meter, m², but in some other power of a meter, mx. Now 4N(L/3)x = NLx, because a three times shorter steplength requires four times as many steps, as is seen from the figure. Solving that equation gives x = (log 4)/(log 3) ≈ 1.26186. So the unit of measurement of the boundary of the Koch snowflake is approximately m1.26186.

Generating fractals

|

|

|

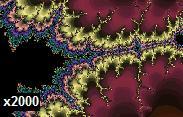

Even 2000 times magnification of the Mandelbrot set uncovers fine detail resembling the full set. Even 2000 times magnification of the Mandelbrot set uncovers fine detail resembling the full set. |

Three common techniques for generating fractals are:

- Iterated function systems — These have a fixed geometric replacement rule. Cantor set, Sierpinski carpet, Sierpinski gasket, Peano curve, Koch snowflake, Harter-Heighway dragon curve, T-Square, Menger sponge, are some examples of such fractals.

- Escape-time fractals — Fractals defined by a recurrence relation at each point in a space (such as the complex plane). Examples of this type are the Mandelbrot set, the Burning Ship fractal and the Lyapunov fractal.

- Random fractals — Generated by stochastic rather than deterministic processes, for example, fractal landscapes, Lévy flight and the Brownian tree. The latter yields so-called mass- or dendritic fractals, for example, diffusion-limited aggregation or reaction-limited aggregation clusters.

Classification of fractals

Fractals can also be classified according to their self-similarity. There are three types of self-similarity found in fractals:

- Exact self-similarity — This is the strongest type of self-similarity; the fractal appears identical at different scales. Fractals defined by iterated function systems often display exact self-similarity.

- Quasi-self-similarity — This is a loose form of self-similarity; the fractal appears approximately (but not exactly) identical at different scales. Quasi-self-similar fractals contain small copies of the entire fractal in distorted and degenerate forms. Fractals defined by recurrence relations are usually quasi-self-similar but not exactly self-similar.

- Statistical self-similarity — This is the weakest type of self-similarity; the fractal has numerical or statistical measures which are preserved across scales. Most reasonable definitions of "fractal" trivially imply some form of statistical self-similarity. (Fractal dimension itself is a numerical measure which is preserved across scales.) Random fractals are examples of fractals which are statistically self-similar, but neither exactly nor quasi-self-similar.

It should be noted that not all self-similar objects are fractals — e.g., the real line (a straight Euclidean line) is exactly self-similar, but since its Hausdorff dimension and topological dimension are both equal to one, it is not a fractal.

Fractals in nature

Approximate fractals are easily found in nature. These objects display self-similar structure over an extended, but finite, scale range. Examples include clouds, snow flakes, mountains, river networks, and systems of blood vessels.

Trees and ferns are fractal in nature and can be modeled on a computer using a recursive algorithm. This recursive nature is clear in these examples — a branch from a tree or a frond from a fern is a miniature replica of the whole: not identical, but similar in nature.

The surface of a mountain can be modeled on a computer using a fractal: Start with a triangle in 3D space and connect the central points of each side by line segments, resulting in 4 triangles. The central points are then randomly moved up or down, within a defined range. The procedure is repeated, decreasing at each iteration the range by half. The recursive nature of the algorithm guarantees that the whole is statistically similar to each detail.

-

A fractal is formed when pulling apart two glue-covered acrylic sheets.

-

High voltage breakdown within a 4″ block of acrylic creates a fractal Lichtenberg figure.

-

Fractal branching occurs on a microwave-irradiated DVD

-

Romanesco broccoli showing very fine natural fractals

Applications

As described above, random fractals can be used to describe many highly irregular real-world objects. Other applications [1] of fractals include:

- Classification of histopathology slides in medicine

- Generation of new music

- Generation of various art forms

- Signal and image compression

- Seismology

- Computer and video game design, especially computer graphics for organic environments and as part of procedural generation

- Fractography and fracture mechanics

- Fractal antennas — Small size antennas using fractal shapes

See also

- Bifurcation theory

- Butterfly effect

- Chaos theory

- Complexity

- Constructal theory

- Diamond-square algorithm

- Fractal art

- Fractal landscape

- Fractal compression

- Graftal

- Publications in fractal geometry

- Newton fractal

- Recursion

- Turbulence

- Feigenbaum function

References

- Barnsley, Michael F., and Hawley Rising. Fractals Everywhere. Boston: Academic Press Professional, 1993. ISBN 0120790610

- Falconer, Kenneth. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2003. ISBN 0470848618

- Jürgens, Hartmut, Heins-Otto Peitgen, and Dietmar Saupe. Chaos and Fractals: New Frontiers of Science. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1992. ISBN 038797903

- Mandelbrot, Benoît B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co., 1982. ISBN 0716711869

- Peitgen, Heinz-Otto, and Dietmar Saupe, eds. The Science of Fractal Images. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1988. ISBN 0387966080

- Clifford A. Pickover, ed. Chaos and Fractals: A Computer Graphical Journey - A 10 Year Compilation of Advanced Research. Elsevier, 1998. ISBN 0-444-50002-2

- Jesse Jones, Fractals for the Macintosh, Waite Group Press, Corte Madera, CA, 1993. ISBN 1-878739-46-8. Probably the earliest good computer-generator for the masses; the book came with a floppy (unknown if it will still run on later Macintoshs). Good introduction geared toward students at junior-high and high school level. With brief history including Peano and Koch leading to Hausdorff dimension. Examples of imaginary-number math, how to generate a fractal. With formulas and brief explanations for the 69 generator functions supported by the floppy. References a 1985 Scientific American article in A.K. Dewdney's "Computer Recreations" that "...inspired countless programmers to write their own Mandelbrot programs" including, apparently, the author.

- Hans Lauwerier, Fractals: Endlessly Repeated Geometrical Figures, Translated by Sophia Gill-Hoffstadt, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1991. ISBN 0-691-08551-X, cloth. ISBN 0-691-02445-6 paperback. "This book has been written for a wide audience..." Includes sample BASIC programs in an appendix.

External links

- The Chaos Hypertextbook. An introductory primer on chaos and fractals.

- Fractals, in Layman's Terms

- Fractals, fractal dimension, chaos, plane filling curves at cut-the-knot

- Fractal properties

- Information on fractals from FAQS.org

- Fractal dimensions

- Fractal calculus

- Fractal Dimension

- Natural fractals in Grand Canyon

- One Dimensional Dynamical Systems. From UIUC a brief introduction

- Fractal Mountain - JAVA applet

- Quaternion Fractals German script about quaternion fractals

Multiplatform generator programs

- Xaos — free fractal real-time browser for Windows, Mac, Linux; supporting zooming and animation in real time, featuring autopilot. GNU GPL licensed.

- FLAM3 — free advanced iterated function system designer and renderer for all platforms. Windows binaries available. GNU GPL licensed.

- Fract — A web-based fractal zoomer, sending calculated images as bitmaps to the browser. Rather slow.

- Online Fractal Generator — Java applet drawing Mandelbrot and Julia sets. Rather slow. Closed sourced.

Linux generator programs

- Gnofract4d — Interactive editor which can use many fractint formulas. Open source, BSD-licensed.

- IFSgr — free iterated function system grayscale renderer. GNU GPL-licensed. See also its image gallery.

- Review of fractal software packages which run under X11 on Linux

Windows generator programs

- Fractovia's listing of fractal generators is a fairly complete listing of free fractal generators.

- Ultra Fractal — software for Microsoft Windows. Free trial version available.

- Apophysis — A free flame and IFS fractal generator. Used for creating fractal artwork. GNU GPL licensed.

- ChaosPro — freeware for Microsoft Windows featuring real-time exploration, animation and more

- MSPlotter — a freeware Windows-based fractal generator, using fractals to create bitmap images and AVI video clips.

- Fractal Explorer — freeware Windows-based generator. Closed sourced, with source available for a fee.

- Yet Another Fractal Explorer — free Lyapunov fractal renderer with zooming feature. GNU GPL licensed.

- Chaoscope — freeware 3D strange attractor rendering software for Windows

- VisualBots — Freeware multi-agent simulator in Microsoft Excel. Samples include Mandelbrot Explorer and fractal tree projects.

- Fractint — freeware fractal generator for DOS and Windows, with a port to Linux available

- Ktaza — freeware for Microsoft Windows

- Fractal Forge — a free fractal generator. Capable of animations, but with low quality. GNU GPL licenced.

- Pythagorean — two pages of open code for the basic processor.

- Drive Mandelbrot 3 - a free fractal generator with simple depth mapping.

Mac generator programs

- Altivec Fractal Carbon — Mac-based benchmarking utility, using fractals to determine performance.

- IFSLab — a freeware iterated function system fractal generator for Mac OS X.

MorphOS generator programs

- Zone Explorer with support for custom formulas