Hamming distance

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. |

|

|

| |

| |

In information theory, the Hamming distance between two strings of equal length is the number of positions at which the corresponding symbols are different. In another way, it measures the minimum number of substitutions required to change one string into the other, or the minimum number of errors that could have transformed one string into the other.

Examples

The Hamming distance between:

- "karolin" and "kathrin" is 3.

- "karolin" and "kerstin" is 3.

- 1011101 and 1001001 is 2.

- 2173896 and 2233796 is 3.

Special properties

For a fixed length n, the Hamming distance is a metric on the vector space of the words of length n (also known as a Hamming space), as it fulfills the conditions of non-negativity, identity of indiscernibles and symmetry, and it can be shown by complete induction that it satisfies the triangle inequality as well.[1] The Hamming distance between two words a and b can also be seen as the Hamming weight of a−b for an appropriate choice of the − operator.[clarification needed]

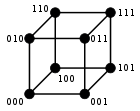

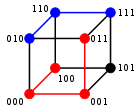

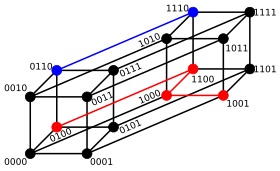

For binary strings a and b the Hamming distance is equal to the number of ones (population count) in a XOR b. The metric space of length-n binary strings, with the Hamming distance, is known as the Hamming cube; it is equivalent as a metric space to the set of distances between vertices in a hypercube graph. One can also view a binary string of length n as a vector in by treating each symbol in the string as a real coordinate; with this embedding, the strings form the vertices of an n-dimensional hypercube, and the Hamming distance of the strings is equivalent to the Manhattan distance between the vertices.

Error detection and error correction

The Hamming distance is used to define some essential notions in coding theory, such as error detecting and error correcting codes. In particular, a code C is said to be k-errors detecting if any two codewords c1 and c2 from C that have a Hamming distance less than k coincide; Otherwise put it, a code is k-errors detecting if and only if the minimum Hamming distance between any two of its codewords is at least k+1.[1]

A code C is said to be k-errors correcting if for every word w in the underlying Hamming space H there exists at most one codeword c (from C) such that the Hamming distance between w and c is less than k. In other words, a code is k-errors correcting if and only if the minimum Hamming distance between any two of its codewords is at least 2k+1. This is more easily understood geometrically as any closed balls of radius k centered on distinct codewords being disjoint.[1] These balls are also called Hamming spheres in this context.[2]

Thus a code with minimum Hamming distance d between its codewords can detect at most d-1 errors and can correct ⌊(d-1)/2⌋ errors.[1] The latter number is also called the packing radius or the error-correcting capability of the code.[2]

History and applications

The Hamming distance is named after Richard Hamming, who introduced it in his fundamental paper on Hamming codes Error detecting and error correcting codes in 1950.[3] It is used in telecommunication to count the number of flipped bits in a fixed-length binary word as an estimate of error, and therefore is sometimes called the signal distance. Hamming weight analysis of bits is used in several disciplines including information theory, coding theory, and cryptography. However, for comparing strings of different lengths, or strings where not just substitutions but also insertions or deletions have to be expected, a more sophisticated metric like the Levenshtein distance is more appropriate. For q-ary strings over an alphabet of size q ≥ 2 the Hamming distance is applied in case of orthogonal modulation, while the Lee distance is used for phase modulation. If q = 2 or q = 3 both distances coincide.

The Hamming distance is also used in systematics as a measure of genetic distance.[4]

On a grid such as a chessboard, the Hamming distance is the minimum number of moves it would take a rook to move from one cell to the other.

Algorithm example

The Python function hamming_distance() computes the Hamming distance between

two strings (or other iterable objects) of equal length, by creating a sequence of Boolean values indicating mismatches and matches between corresponding positions in the two inputs, and then summing the sequence with False and True values being interpreted as zero and one.

def hamming_distance(s1, s2):

"""Return the Hamming distance between equal-length sequences"""

if len(s1) != len(s2):

raise ValueError("Undefined for sequences of unequal length")

return sum(ch1 != ch2 for ch1, ch2 in zip(s1, s2))

The following C function will compute the Hamming distance of two integers (considered as binary values, that is, as sequences of bits). The running time of this procedure is proportional to the Hamming distance rather than to the number of bits in the inputs. It computes the bitwise exclusive or of the two inputs, and then finds the Hamming weight of the result (the number of nonzero bits) using an algorithm of Wegner (1960) that repeatedly finds and clears the lowest-order nonzero bit.

int hamming_distance(unsigned x, unsigned y)

{

int dist;

unsigned val;

dist = 0;

val = x ^ y; // XOR

// Count the number of bits set

while (val != 0)

{

// A bit is set, so increment the count and clear the bit

dist++;

val &= val - 1;

}

// Return the number of differing bits

return dist;

}

See also

- Closest string

- Damerau–Levenshtein distance

- Euclidean distance

- Mahalanobis distance

- Jaccard index

- String metric

- Sørensen similarity index

- Word ladder

Notes

- ^ a b c d Derek J.S. Robinson (2003). An Introduction to Abstract Algebra. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 255–257. ISBN 978-3-11-019816-4.

- ^ a b Cohen, G.; Honkala, I.; Litsyn, S.; Lobstein, A. (1997), Covering Codes, North-Holland Mathematical Library, vol. 54, Elsevier, pp. 16–17, ISBN 9780080530079

- ^ Hamming (1950).

- ^ Pilcher, Wong & Pillai (2008).

References

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.- Hamming, Richard W. (1950), "Error detecting and error correcting codes" (PDF), Bell System Technical Journal, 29 (2): 147–160, doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1950.tb00463.x, MR 0035935.

- Pilcher, C. D.; Wong, J. K.; Pillai, S. K. (March 2008), "Inferring HIV transmission dynamics from phylogenetic sequence relationships", PLoS Med., 5 (3): e69, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050069, PMC 2267810, PMID 18351799

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link). - Wegner, Peter (1960), "A technique for counting ones in a binary computer", Communications of the ACM, 3 (5): 322, doi:10.1145/367236.367286.