Extermination through labour

Extermination through labor is a term sometimes used to describe the operation of concentration camp, death camp and forced labor systems in Nazi Germany, Soviet Union, North Korea, and elsewhere, defined as the willful or accepted killing of forced laborers or prisoners through excessively heavy labor, malnutrition and inadequate care.

Use as a term

The term "extermination through labor" (Vernichtung durch Arbeit) was not generally used by the Nazi SS but the phrase was notably used in the fall of 1942 in negotiations between Albert Bormann, Joseph Goebels, Otto Georg Thierack and Heinrich Himmler, relating to the transfer of prisoners to concentration camps. Thierack and Goebbels specifically used the term.[1] The phrase was used again during the post-war Nuremberg trials.[1]

In the 1980s and 1990s, however, historians have debated the appropriate use of the term. Falk Pingel believed the phrase should not be applied to all Nazi prisoners, while Hermann Kaienburg and Miroslav Kárný believed "extermination through labour" was a consistent goal of the SS. More recently, Jens-Christian Wagner has also argued that not all Nazi prisoners were targeted with annihilation.[1]

In Nazi Germany

The Nazis persecuted many individuals because of their race, political affiliation, disability, religion or sexual orientation.[2][3] Groups marginalized by the majority population in Germany included welfare-dependent families with many children, alleged vagrants and transients, as well as members of the perceived problem groups such as alcoholics and prostitutes. While these people were considered "German-blooded," they were also categorized as "social misfits," as well as superfluous "ballast-lives." They were recorded in lists (as were homosexuals) by civil and police authorities and subjected to a myriad of state restrictions and repressive actions, which included forced sterilization and ultimately imprisonment in concentration camps. Anyone who openly opposed the Nazi regime (such as communists, social democrats, democrats, and conscientious objectors) was detained in prison camps. Many of them did not survive the ordeal.[2]

While others could possibly redeem themselves in the eyes of the Nazis, there was no room in Hitler's world-view for Jews, although Germany encouraged and supported emigration of Jews to Palestine and elsewhere from 1933 until 1941 with arrangements such as the Haavara Agreement, or the Madagascar Plan. During the war in 1942 the Nazi leadership gathered to discuss what had come to be called "the final solution to the Jewish question" at a conference in Wannsee, Germany. The transcript of this gathering gives historians insight into the thinking of the Nazi Leadership, as they devised the salient details of their future destruction, including using extermination through labor as one component of their so-called "Final Solution".[4]

Under proper leadership, the Jews shall now in the course of the Final Solution be suitably brought to their work assignments in the East. Able-bodied Jews are to be led to these areas to build roads in large work columns separated by sex, during which a large part will undoubtedly drop out through a process of natural reduction. As it will undoubtedly represent the most robust portion, the possible final remainder will have to be handled appropriately, as it would constitute a group of naturally-selected individuals, and would form the seed of a new Jewish resistance. — Wannsee Protocol, 1942. [4]

In Nazi camps, "extermination through labor" was principally carried out through a slave-based labor organization, which is why, in contrast with the forced labor of foreign work forces, a term from the Nuremberg Trials is used for "slave work" and "slave workers."[2]

Working conditions were characterized by: no remuneration of any kind; constant surveillance of workers; physically demanding labor (for example, road construction, farm work, and factory work, particularly in the arms industry); excessive working hours (often 10 to 12 hours per day); minimal nutrition, food rationing; lack of hygiene; poor medical care and ensuing disease; insufficient clothing (for example, summer clothes even in the winter).

They also used torture and physical abuse. Torstehen ("Gate Hanging") – forced victims to stand outside naked with arms raised – like a gate hanging on its hinges. When they collapsed or passed out, they would be beaten until they re-assumed the position. Pfahlhängen ("Post Attachment") involved tying the inmate's hands behind their back and then hanging them by their hands from a tall stake. This would dislocate and disjoint the arms and the pressure would be fatal within hours. (Cf. strappado.)

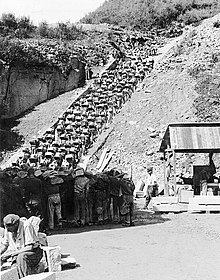

Concentration camps

Imprisonment in concentration camps was intended not merely to break, but to destroy inmates. The admission and registration of the new prisoners, the forced labor, the prisoner housing, the roll calls—all aspects of camp life were accompanied by humiliation and harassment.

Admission, registration and interrogation of the detainees was accompanied by scornful remarks from SS officials. The prisoners were stepped on and beaten during roll call. Forced labor partly consisted of pointless tasks and heavy labor, which was intended to wear down the prisoners.[2]

At many of the concentration camps, forced labor was channeled for the advancement of the German war machine. In these cases, excessive working hours were also seen as a means to maximizing output. Oswald Pohl, the leader of the SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt ("SS Economy and Administration Main Bureau", or SS-WVHA), who oversaw the employment of slave labor at the concentration camps, ordered on April 30, 1942.[5]

The camp commander alone is responsible for the use of man power. This work must be exhausting in the true sense of the word in order to achieve maximum performance. […] There are no limits to working hours. […] Time consuming walks and mid-day breaks only for the purpose of eating are prohibited. […] He [the camp commander] must connect clear technical knowledge in military and economic matters with sound and wise leadership of groups of people, which he should bring together to achieve a high performance potential.[5]

Up to 25,000 of the 35,000 prisoners appointed to work for IG Farben in Auschwitz died. The average life expectancy of a Jewish prisoner on a work assignment amounted to less than four months.[6] The emaciated forced laborers died from exhaustion or disease or they were deemed to be incapable of work and killed. About 30 percent of the forced laborers who were assigned to dig tunnels, which were created for weapon factories in the last months of the war, died.[7] In the satellite camps, which were established in the vicinity of mines and industrial firms, death rates were even higher, since accommodations and supplies were often even less adequate there than in the main camps.

The phrase "Arbeit macht frei" ("work shall set you free"), which could be found in various places in some Nazi concentration camps, e.g. on the entrance gates, seems particularly cynical in this context. The Buchenwald concentration camp was the only concentration camp with the motto "Jedem das Seine" ("To each what he deserves") on the entrance gate.

In the Soviet Union

The Soviet Gulag is sometimes presented as a system of death camps,[8][9][10][11] though this is controversial, considering that with the obvious exception of the war years, a very large majority of people who entered the Gulag left alive.[12] Alexander Solzhenitsyn introduced the expression camps of extermination by labor in his novel The Gulag Archipelago.[13] According to him, the system eradicated opponents by forcing them to work as prisoners on big state-run projects (for example the White Sea-Baltic Canal, quarries, remote railroads and urban development projects) under inhumane conditions. Roy Medvedev comments: "The penal system in the Kolyma and in the camps in the north was deliberately designed for the extermination of people."[11] Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev expands upon this, claiming that Stalin was the "architect of the gulag system for totally destroying human life."[14] Writer Stephen Wheatcroft argues that the scale and nature of the Soviet Gulag repressions need to be looked at through the perspective of greater populations of the USSR.[15]

According to formerly secret internal Gulag documents, some 1.6 million people must have died in the period between 1930 and 1956 in Soviet forced labor camps and colonies (excluding prisoner of war camps), though these figures only include the deaths in the colonies beginning in 1935. The majority (about 900,000) of these deaths therefore fall between 1941 and 1945,[16] coinciding with the period of German-Soviet War when food supply levels were low in the entire country.

These figures are consistent with the archived documents that Russian historian Oleg Khlevniuk presents and analyzes in his study The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror, according to which some 500,000 people died in the camps and colonies from 1930 to 1941.[17] Khlevniuk points out that these figures don't take into account any deaths that occurred during transport.[18] Also excluded are those who died shortly after their release due to the harsh treatment in the camps,[19] who, according to both archives and memoirs, were numerous.[20] The historian J. Otto Pohl estimates that some 2,749,163 prisoners perished in the labor camps, colonies and special settlements, although stresses that this is an incomplete figure.[21] Though the death toll is still widely debated, no state or national institution has recognized the Gulag system as a genocide.

It is believed that similar camps are operating in North Korea, killing at least 20,000 political prisoners.[22][23]

See also

- Forced labor in Germany during World War II

- Forced labor of Germans after World War II

- Hunger Plan, a German plan to starve the Slavic and Jewish populations

- Penal labor

References

- ^ a b c Buggeln, Marc (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–. ISBN 9780198707974. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Robert Gellately; Nathan Stoltzfus (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-691-08684-2.

- ^ Hitler's Ethic By Richard Weikar, page 73.

- ^ a b Wannsee Protocol, January 20, 1942. The official U.S. government translation prepared for evidence in trials at Nuremberg.

- ^ a b IMT: Der Nürnberger Prozess. Volume XXXVIII, p. 366 / document 129-R.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: Die Vernichtung der europäischen Juden. extended edition Frankfurt 1990. ISBN 3-596-24417-X Volume 2 Page 994f

- ^ Michael Zimmermann: Kommentierende Bemerkungen – Arbeit und Vernichtung im KZ-Kosmos. In: Ulrich Herbert et al. (Ed.): Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. Frankfurt/M 2002, ISBN 3-596-15516-9, Vol. 2, p. 744

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn Lexikon der Völkermorde, Rowohlt rororo 1998, ISBN 3-499-22338-4

- ^ Joel Kotek / Pierre Rigoulot Gefangenschaft, Zwangsarbeit, Vernichtung, Propyläen 2001

- ^ Ralf Stettner Archipel Gulag. Stalins Zwangslager, Schöningh 1996, ISBN 3-506-78754-3

- ^ a b Roy Medwedew Die Wahrheit ist unsere Stärke. Geschichte und Folgen des Stalinismus (Ed. by David Joravsky and Georges Haupt), Fischer, Frankfurt/M. 1973, ISBN 3-10-050301-5

- ^ http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/mar/10/hitler-vs-stalin-who-killed-more/

- ^ Alexander Solzhenitsyn Arkhipelag Gulag, Vol. 2. "Novyy Mir," 1990.

- ^ Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev. A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-08760-8 p. 15

- ^ Stephen Wheatcroft, The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 48, No. 8 (Dec., 1996), pp. 1319–1353

- ^ A. I. Kokurin / N. V. Petrov (Ed.): GULAG (Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerej): 1918–1960 (Rossija. XX vek. Dokumenty), Moskva: Materik 2000, ISBN 5-85646-046-4, pp. 441–2

- ^ Oleg V. Khlevniuk: The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror New Haven: Yale University Press 2004, ISBN 0-300-09284-9, pp. 326–7.

- ^ ibd., pp. 308–6.

- ^ Ellman, Michael. Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments Europe-Asia Studies. Vol 54, No. 7, 2002, 1151–1172

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1 pg 583

- ^ Pohl, The Stalinist Penal System, p. 131.

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/northkorea/10288945/Up-to-20000-North-Korean-prison-camp-inmates-have-disappeared-says-human-rights-group.html

- ^ http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/northkorea/2014/08/14/99/0401000000AEN20140814002300315F.html

Further reading

- Template:De icon Stéphane Courtois: Das Schwarzbuch des Kommunismus, Unterdrückung, Verbrechen und Terror. Piper, 1998. 987 pages. ISBN 3-492-04053-5

- Template:De icon Jörg Echternkamp: Die deutsche Kriegsgesellschaft: 1939 bis 1945: Halbband 1. Politisierung, Vernichtung, Überleben. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 2004. 993 pages, graphic representation. ISBN 3-421-06236-6

- Oleg V. Khlevniuk: The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror New Haven: Yale University Press 2004, ISBN 0-300-09284-9

- Template:Ru icon A. I. Kokurin/N. V. Petrov (Ed.): GULAG (Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerej): 1918–1960 (Rossija. XX vek. Dokumenty), Moskva: Materik 2000, ISBN 5-85646-046-4

- Template:De icon Joel Kotek/Pierre Rigoulot: Das Jahrhundert der Lager.Gefangenschaft, Zwangsarbeit, Vernichtung, Propyläen 2001, ISBN 3-549-07143-4

- Template:De icon Rudolf A. Mark (Ed.): Vernichtung durch Hunger: der Holodomor in der Ukraine und der UdSSR. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin, Berlin 2004. 207 pages ISBN 3-8305-0883-2

- Hermann Kaienburg (1990). Vernichtung durch Arbeit. Der Fall Neuengamme (Extermination through labour: Case of Neuengamme) (in German). Bonn: Dietz Verlag J.H.W. Nachf. p. 503. ISBN 3-8012-5009-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Gerd Wysocki (1992). Arbeit für den Krieg (Work for the War) (in German). Braunschweig. ISBN.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Donald Bloxham (2001). Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 296. ISBN 0-19-820872-3.

- Nikolaus Wachsmann (1999). "Annihilation through Labor: The Killing of State Prisoners in the Third Reich". Journal of Modern History. 71 (3): 624–659. doi:10.1086/235291. JSTOR 2990503.

- various authors (2002). Michael Berenbaum, Abraham J Peck (ed.). The Holocaust and History: The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed, and the Reexamined. Indiana University Press. pp. 370–407. ISBN 0-253-21529-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - Eugen Kogon; Heinz Norden; Nikolaus Wachsmann (2006). The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System Behind Them. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 368. ISBN 0-374-52992-2.