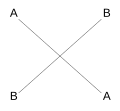

Chiasmus

In rhetoric, chiasmus, or less commonly chiasm, (Latin term from Greek χίασμα, "crossing", from the Greek χιάζω, chiázō, "to shape like the letter Χ") is the figure of speech in which two or more clauses are presented to the reader or hearer, then presented again in reverse order, in order to make a larger point. To diagram a simple chiasmus, the clauses are often labelled in the form A B B A. For example, John F. Kennedy said, "ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country". The initial clauses 'your country':'you' are reversed in the second half of the sentence to 'you':'your country'. This is often used to invite the reader or hearer to reconsider the relationship between the repeated clauses.

In chiasmus, the clauses display inverted parallelism. Chiasmus was particularly popular in the literature of the ancient world, including Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, where it was used to articulate the balance of order within the text. As a popular example, many long and complex chiasmi have been found in Shakespeare[1] and the Greek and Hebrew texts of the Bible.[2] It is also found throughout the Book of Mormon[3] and Quran.[4]

Today, chiasmus is applied fairly broadly to any "criss-cross" structure, although in classical rhetoric it was distinguished from other similar devices, such as the antimetabole.[citation needed] In its classical application, chiasmus would have been used for structures that do not repeat the same words and phrases, but invert a sentence's grammatical structure or ideas. The concept of chiasmus on a higher level, applied to motifs, turns of phrase, or whole passages, is called chiastic structure.

Inverted meaning

But O, what damned minutes tells he o'er

Who dotes, yet doubts; suspects, yet strongly loves.

—Shakespeare, Othello 3.3

"Dotes" and "strongly loves" share the same meaning and bracket "doubts" and "suspects".

| A | B | B | A |

| dotes | doubts | suspects | strongly loves |

"Fair is foul, and foul is fair"

—Shakespeare, Macbeth 1.1

| A | B | B | A |

| fair | foul | foul | fair |

Conceptual chiasmus

Chiasmus can be used in the structure of entire passages to parallel concepts or ideas. This process, termed "conceptual chiasmus", uses a criss-crossing rhetorical structure to cause an overlapping of "intellectual space".[5] Conceptual chiasmus utilizes specific linguistic choices, often metaphors, to create a connection between two differing disciplines.[5] By employing a chiastic structure to a single presented concept, rhetors encourage one area of thought to consider an opposing area's perspective.

Effectiveness of chiasmus

Chiasmus derives its effectiveness from its symmetrical structure. The structural symmetry of the chiasmus imposes the impression upon the reader or listener that the entire argument has been accounted for.[6] In other words, chiasmus creates only two sides of an argument or idea for the listener to consider, and then leads the listener to favor one side of the argument. In former President John F. Kennedy's famous quote, "ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country",[7] the only two questions that the chiastic statement allows for are whether the listener should ask what the country can do for him, or ask what he can do for his country. The statement also proposes that the latter statement is more favorable. Thus, chiasmus gains its rhetorical efficacy through symmetrical structure causing the belief that all tenets of an argument have been evaluated.

Thematic chiasmus

The Wilhelmus, the national anthem of the Netherlands, has a structure composed around a thematic chiasmus: the 15 stanzas of the text are symmetrical, in that verses one and 15 resemble one another in meaning, as do verses two and 14, three and 13, etc., until they converge in the eighth verse, the heart of the song. Written in the 16th century, the Wilhelmus originated in the nation's struggle to achieve independence. It tells of the Father of the Nation William of Orange who was stadholder in the Netherlands under the king of Spain. In the first person, as if quoting himself, William speaks to the Dutch people and tells about both the outer conflict – the Dutch Revolt – as well as his own, inner struggle: on one hand, he tries to be faithful to the king of Spain,[8] on the other hand he is above all faithful to his conscience: to serve God and the Dutch people. This is made apparent in the central 8th stanza: "Oh David, thou soughtest shelter from King Saul's tyranny. Even so I fled this welter". Here the comparison is made between the biblical David and William of Orange as merciful and just leaders who both serve under tyrannic kings. As the merciful David defeats the unjust Saul and is rewarded by God with the kingdom of Israel, so too, with the help of God, will William be rewarded a kingdom; being either or both the Netherlands, and the kingdom of God.[9]

See also

- Arch form

- Antanaclasis

- Antimetabole

- Chiastic structure

- Figure of speech

- Golden line (a Latin poetic line based on an abAB structure)

- Rhetoric

- Russian reversal

- Silver line (a Latin poetic line based on an abBA structure)

- Spoonerism

- Synchysis (the reverse of the chiasmus)

- Transpositional pun

- The Throne Verse

- Contrapposto

Further reading

- Lund, Nils Wilhelm (1942). Chiasmus in the New Testament, a study in formgeschichte. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. OCLC 2516087.

- McCoy, Brad (Fall 2003). "Chiasmus: An Important Structural Device Commonly Found in Biblical Literature" (PDF). CTS Journal. 9 (2). Albuquerque, New Mexico: Chafer Theological Seminary: 18–34.

- Parry, Donald W. (2007). Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon (PDF). Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship. ISBN 978-0-934893-36-7.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). A Greek Grammar for Colleges. New York: American Book Company. p. 677. OCLC 402001.

- Welch, John W. (1995). "Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus". Journal of Book of Mormon Studies. 4 (2). Brigham Young University.

- Welch, John W. (1999) [1981]. Chiasmus in antiquity: structures, analyses, exegesis. Provo, Utah: Research Press. ISBN 0934893330. OCLC 40126818.

External links

- Chiasmus, Rhetorical Figures, by Gideon O. Burton (Professor of Rhetoric and Composition, BYU), at humanities.byu.edu/rhetoric

- Chiasmus Explained at LiteraryDevices

Notes

- ^ Ramirez, Matthew Eric (January 2011). "Descanting on Deformity: The Irregularities in Shakespeare's Large Chiasms". Text and Performance Quarterly. 31 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1080/10462937.2010.526240.

- ^ Breck, John (1994). The Shape of Biblical Language: Chiasmus in the Scriptures and Beyond. Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-8814-1139-3. OCLC 30893460.

- ^ "Alma 36: 3-27". Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Ahmadi, Mohamadnabi. "Semantic and Rhetorical Aspects of Chiasmus in the Holy Quran". Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Ceccarelli, Leah (2001). Shaping Science with Rhetoric: The Cases of Dobzhansky, Schrödinger, and Wilson. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 5. ISBN 0226099067. OCLC 45276826.

- ^ Lissner, Patricia (2007). Chi-thinking: Chiasmus and Cognition (PDF). University of Maryland. p. 217. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Kennedy, John. "Inaugural Address". American Rhetoric. American Rhetoric. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ CF.hum.uva.nl

- ^ DeLapp, Nevada Levi (August 28, 2014). The Reformed David(s) and the Question of Resistance to Tyranny: Reading the Bible in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 87–89. ISBN 9780567655493.