User:Littlesheep123/sandbox

Irish Folklore

Irish folklore. The lead section (first paragraph) will be your introduction.

What other sections do you plan to have in your article? (Susan)

Folklore Cite error: The opening <ref> tag is malformed or has a bad name (see the help page). "is the traditional art, literature, knowledge, and practice that is disseminated largely through oral communication and behavioural example"[1]. Folklore is a part of a groups identity, their traditions, beliefs, worldviews, knowledge (how to build a house, how to treat an illness), skills (art) and talents ( story-telling, songs, plays). Folklore is a big part of a groups', countries' culture. Due to its complexity folklore has no one definition[2].

Irish Folklore when mentioned to many people conjures up images of banshees, fairy stories and leprechauns and people gathered around sharing stories of a man as strong a 300 men put together. This is all well and good but there is an academic value to folklore as it gives an insight into people's daily life, their hopes and fears. When studied an understanding of how we live and why we do the things we do is involved. There are central significant characteristics in the Irish folklore tradition;the Irish language, our literary and linguistic inheritance and religion, both pre-christian and christian[3].

Folklore is about people. Just as many tales and legends were passed from generation to generations so are how we celebrate important moment such as marriages, deaths, birthday and holidays ( Christmas, Halloween( Oíche Shamhna), St. Patrick's Day) and also how we hand down skills such as making weaved baskets, St. Bridget's crosses. This is all Folklore as it is the study and appreciation of how people lived.[3]

Classic Irish folklore

Irish folklore consists of many classics that are repeated to this day. Folktales which are popular in Ireland consist of the Otherworld ( An Saol Eile ), which revolves around the idea of supernatural manifestations and beings. [4]These beings are shown in many of the folkloristic genres such as ballads, popular song, legends, memorates, belief statements and folkloric material.[4] Some famous examples from this include the Irish fairylore and restless souls and spirits around Halloween , for example the Banshee.[4]

The Banshee is one of the most popular classics to this day ,known by many different names for example Badh commonly used in the south of Ireland.[5] The Banshee is also rumoured to have a connection with certain families is said to follow the prominent male members of the family.[5] Popular opinion is also that she is seen as the ancestress of Irish families and is deeply concerned with the families fortunes. [5]It is uncertain whether the Banshee is evil or good.

Other classics include , leprechauns , fairies, rainbows , Cu Chluain , Children of Lir , Dullahan (headless horsemen), Pookas , Changelings .

Traditions in Irish Folklore

The word folklore in French means “picturesque but without importance or without deep significance”.[6] In Ireland the word Folk Lore has deep meaning to it's people and brings societies together, it is a word that has ideological significance in this country. In Ireland folklore can be associated with the countryside , specifically the Irish speaking West, Aran Islands , oral stories , the fiddle , intimate settings. Folklore is also massively tied with traditional Irish music and dance for example the river dance can be tied to folklore in ways. [6]

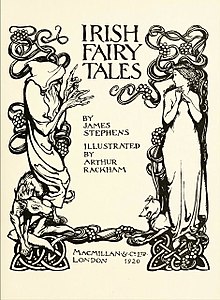

FairyLore

Seán Ó Súilleabháin (1903-1996) and the Irish Folklore Commission

Ó Súilleabháin was part of the Irish Folklore Commision , Béaloideas. Not long after the foundation of the commission he created two books for the collectors. The first, in 1937, a shorter volume in the Irish Language, Láimh-Leabhar Béaloideasa, mainly used by collectors in the Irish speaking areas. In 1942 he wrote his more well-known volume A Handbook of Irish Folklore (published 1947). To this day his work serves as a great resource to collectors of Irish folklore and provides a wide outline of the traditions of Irish Folklore.[7]

He also wrote a booklet of topics, in both Irish and English, in 1937 to be used by teachers and school children in primary schools in the South of Ireland as part of the Schools' Scheme for the collection of folklore (1937-1938).[7]

He focused on the native Gaelic tradition and the tradition of story-tellying. he played particular attention to the stories of Fionn Mac Cumhail and the Fianna.he also looked into how stories were told in Irish and in other languages across Europe. His work has and still is very important in the study of Irish Folklore for the masses.[7]

The evolution of Irish Folklore

Folklore is a part of national identity, and is evolving through time. During the 17th century, the English conquest as overthrown the traditional political and religious autonomy of the country. The Great famine of 1840’s, and the deaths and emigration it has brought, weakened a still powerful Gaelic culture, especially within the rural proletariat, which was at the time the most traditional social grouping. At the time, intellectuals such as Sir William Wilde were expressing concerns on the decay of traditional beliefs:

“In the state of things, with depopulation the most terrific which any country ever experienced, on the one hand, and the spread of education, and the introduction of railroads, colleges, industrial and other educational schools, on the other – together with the rapid decay of our Irish bardic annals, the vestige of Pagan rites, and the relics of fairy charms were preserved, - can superstition, or if superstitious belief, can superstitious practices continue to exist? “[6]

Moreover, in the last decades, capitalism has helped overcoming special spatial barriers[8] making it easier for cultures to merge into one another (such as the amalgam between Samhain and Halloween).

All those events have led to a massive decline of native learned Gaelic traditions and Irish language, and with Irish tradition being mainly an oral tradition[9], this has lead to a loss of identity and historical continuity, in a similar nature to Durkheim’s anomie.[10]

Honko (1991) describes the current state of the Irish folklore as its “second life”. Even though there is still a natural existence of folklore within its natural community, folklore material is now being used in other environments, such as marketing (with strategies suggesting tradition and authenticity for goods), movies and TV-shows (The Secret of Kells, mention of the Bashee are found in in tv-shows such as Supernatural or Teen Wolf), books (the book series The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel), contributing to the creation of a new body of Irish folklore.

See Also

Irish mythology in popular culture

Hebridean mythology and folklore

- ^ "What Is Folklore? - American Folklore Society". afsnet.site-ym.com. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ "What is Folklore? – Social Sciences, Health, and Education Library (SSHEL) – U of I Library". www.library.illinois.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ a b "Irish Folklore: Myth and Reality". dominican-college.com. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ a b c 1958-, O'Connor, Anne, (2005). The blessed and the damned : sinful women and unbaptised children in Irish folklore. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 3039105418. OCLC 62533994.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c The concept of the goddess. Billington, Sandra., Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. (Miranda Jane). London: Routledge. 1996. ISBN 0415197899. OCLC 51912602.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c 1955-, Ó Giolláin, Diarmuid, (2000). Locating Irish folklore : tradition, modernity, identity. Sterling, VA: Cork University Press. ISBN 1859181694. OCLC 43615310.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lysaght, Patricia (1998). "Seán Ó Súilleabháin (1903-1996) and the Irish Folklore Commission". Western Folklore. 57 (2/3): 137–151. doi:10.2307/1500217.

- ^ 1935-, Harvey, David, (1990). The condition of postmodernity : an enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Oxford [England]: Blackwell. ISBN 0631162941. OCLC 18747380.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "A Guide to Irish Folk Tales". Owlcation. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ^ 1955-, Ó Giolláin, Diarmuid, (2000). Locating Irish folklore : tradition, modernity, identity. Sterling, VA: Cork University Press. ISBN 1859181694. OCLC 43615310.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)