Untermensch

Untermensch (German pronunciation: [ˈʔʊntɐˌmɛnʃ], underman, sub-man, subhuman; plural: Untermenschen) is a term that became infamous when the Nazis used it to describe "inferior people" often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs – mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians.[1][2][3] The term was also applied to blacks and persons of color.[4] Jewish people were to be exterminated in the Holocaust,[5] along with Romani people, and the physically and mentally disabled.[6][7] According to the Generalplan Ost, the Slavic population of East-Central Europe was to be reduced in part through mass murder in the Holocaust, with a majority expelled to Asia and used as slave labor in the Reich. These concepts were an important part of the Nazi racial policy.[8]

Etymology

Although usually incorrectly considered to have been coined by the Nazis, the term "under man" was first used by American author and Klansman Lothrop Stoddard in the title of his 1922 book The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-man.[9] It was later adopted by the Nazis from that book's German version Der Kulturumsturz: Die Drohung des Untermenschen (1925).[10] The German word Untermensch had been used earlier, but not in a racial sense, for example in the 1899 novel Der Stechlin by Theodor Fontane. Since most writers who employed the term did not address the question of when and how the word entered the German language, Untermensch is usually translated into English as "sub-human." The leading Nazi attributing the concept of the East-European "under man" to Stoddard is Alfred Rosenberg who, referring to Russian communists, wrote in his Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts (1930) that "this is the kind of human being that Lothrop Stoddard has called the 'under man.'" ["...den Lothrop Stoddard als 'Untermenschen' bezeichnete."][11] Quoting Stoddard: "The Under-Man – the man who measures under the standards of capacity and adaptability imposed by the social order in which he lives".

It is possible that Stoddard constructed his "under man" as an opposite to Friedrich Nietzsche's Übermensch (superman) concept. Stoddard does not say so explicitly, but he refers critically to the "superman" idea at the end of his book (p. 262).[9] Wordplays with Nietzsche's term seem to have been used repeatedly as early as the 19th century and, due to the German linguistic trait of being able to combine prefixes and roots almost at will in order to create new words, this development can be considered logical. For instance, German author Theodor Fontane contrasts the Übermensch/Untermensch word pair in chapter 33 of his novel Der Stechlin.[12] Nietzsche used Untermensch at least once in contrast to Übermensch in Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (1882); however, he did so in reference to semi-human creatures in mythology, naming them alongside dwarfs, fairies, centaurs and so on.[13] Earlier examples of Untermensch include Romanticist Jean Paul using the term in his novel Hesperus (1795) in reference to an Orangutan (Chapter "8. Hundposttag").[14]

Nazi propaganda and policy

In a speech in 1927 to the Bavarian regional parliament, the Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, publisher of Der Stürmer, used the term Untermensch referring to the communists of the German Bavarian Soviet Republic:

- It happened at the time of the [Bavarian] Soviet Republic: When the unleashed subhumans rambled murdering through the streets, the deputies hid behind a chimney in the Bavarian parliament.[15]

Nazis repeatedly used the term Untermensch in writings and speeches directed against the Jews, the most notorious example being a 1935 SS publication with the title Der Untermensch, which contains an antisemitic tirade sometimes considered to be an extract from a speech by Heinrich Himmler. In the pamphlet "The SS as an Anti-Bolshevist Fighting Organization", published in 1936, Himmler wrote:

We shall take care that never again in Germany, the heart of Europe, will the Jewish-Bolshevistic revolution of subhumans be able to be kindled either from within or through emissaries from without.[16][17][18]

In his speech "Weltgefahr des Bolschewismus" ("World danger of Bolshevism") in 1936, Joseph Goebbels said that "subhumans exist in every people as a leavening agent".[19] At the 1935 Nazi party congress rally at Nuremberg, Goebbels also declared that "Bolshevism is the declaration of war by Jewish-led international subhumans against culture itself."[20]

Another example of the use of the term Untermensch, this time in connection with anti-Soviet propaganda, is a brochure entitled "Der Untermensch", edited by Himmler and distributed by the Race and Settlement Head Office. SS-Obersturmführer Ludwig Pröscholdt, Jupp Daehler and SS-Hauptamt-Schulungsamt Koenig are associated with its production.[4] Published in 1942 after the start of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, it is around 50 pages long and consists for the most part of photos portraying the enemy in an extremely negative way (see link below for the title page). 3,860,995 copies were printed in the German language. It was translated into Greek, French, Dutch, Danish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Czech and seven other languages. The pamphlet says the following:

Just as the night rises against the day, the light and dark are in eternal conflict. So too, is the subhuman the greatest enemy of the dominant species on earth, mankind. The subhuman is a biological creature, crafted by nature, which has hands, legs, eyes and mouth, even the semblance of a brain. Nevertheless, this terrible creature is only a partial human being.

Although it has features similar to a human, the subhuman is lower on the spiritual and psychological scale than any animal. Inside of this creature lies wild and unrestrained passions: an incessant need to destroy, filled with the most primitive desires, chaos and coldhearted villainy.

A subhuman and nothing more!

Not all of those who appear human are in fact so. Woe to him who forgets it!

Mulattoes and Finn-Asian barbarians, Gipsies and black skin savages all make up this modern underworld of subhumans that is always headed by the appearance of the eternal Jew.[4]

Nazis classified those they called the sub-humans into different types; they placed priority on extermination of the Jews, and exploitation of others as slaves.[21]

Historian Robert Jan van Pelt writes that for the Nazis, "it was only a small step to a rhetoric pitting the European Mensch against the Soviet Untermensch, which had come to mean a Russian in the clutches of Judeo-Bolshevism."[22]

The Untermensch concept included Jews, Roma and Sinti (Gypsies), and Slavic peoples such as Poles, Serbs and Russians.[8] The Slavs were regarded as Untermenschen, barely fit for exploitation as slaves.[23][24] Hitler and Goebbels compared them to the "rabbit family" or to "stolid animals" that were "idle" and "disorganized" and spread like a "wave of filth".[25]

While the Nazis were inconsistent in the implementation of their policy (mostly implementing the Final Solution while implementing Generalplan Ost), the democidal death toll was in tens of millions of victims.[26][27] It is related to the concept of "life unworthy of life", a more specific term which originally referred to the severely disabled who were involuntarily euthanised in Action T4, and was eventually applied to the extermination of the Jews.

In the directive No. 1306 by Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda from October 24th 1939, the term "Untermensch" is used in reference to Polish ethnicity and culture, as follows:

It must become clear to everybody in Germany, even to the last milkmaid, that Polishness is equal to subhumanity. Poles, Jews and Gypsies are on the same inferior level. This must be clearly outlined [...] until every citizen of Germany has it encoded in his subconsciousness that every Pole, whether a worker or intellectual, should be treated like vermin".[28][29]

Biology classes in Nazi Germany schools taught about differences between the race of Nordic German "Übermenschen" and "ignoble" Jewish and Slavic "subhumans".[30] The view that Slavs were subhuman was widespread among the German masses, and chiefly applied to the Poles. It continued to find support after the war.[31]

During the war, Nazi propaganda instructed Wehrmacht officers told their soldiers to target people described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans" and that the war in the Soviet Union was between the Germans and the Jewish, Gypsies and Slavic Untermenschen.[32][33]

During the Warsaw Uprising, Himmler ordered the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto because according to him it allowed the "living space" of 500,000 subhumans.[34][35]

As a pragmatic way to solve military manpower shortages, the Nazis used soldiers from some Slavic countries, firstly from the Reich's allies Croatia and Bulgaria[36] and also within occupied territories.[37] The concept of the Slavs in particular being Untermenschen served the Nazis' political goals; it was used to justify their expansionist policy and especially their aggression against Poland and the Soviet Union in order to achieve Lebensraum, particularly in Ukraine. Early plans of the German Reich (summarized as Generalplan Ost) envisioned the displacement, enslavement, and elimination of no fewer than 50 million people, who were not considered fit for Germanization, from territories it wanted to conquer in Europe; Ukraine's chernozem ("black earth") soil was considered a particularly desirable zone for colonization by the Herrenvolk ("master race").[8]

See also

- Eugenics

- Genocides in Nazi Germany and occupied Europe

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Mischling

- Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles

- Nuremberg Laws

- Rassenschande

- Racial hygiene

- Übermensch

- World War II persecution of Serbs

References

- ^ Revisiting the National Socialist Legacy: Coming to Terms With Forced Labor, Expropriation, Compensation, and Restitution page 84 Oliver Rathkolb

- ^ Gumkowski, Janusz; Leszczynski, Kazimierz; Robert, Edward (translator) (1961). Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe (First ed.). Polonia Pub. House. p. 219. ASIN B0006BXJZ6. Archived from the original (Paperback) on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

{{cite book}}:|first3=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) at Wayback machine. - ^ Shirer, William L. (1960) The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp.937, 939. Quotes: "The Jews and the Slavic people were the Untermenschen – subhumans." (937); "[The] obsession of the Germans with the idea that they were the master race and that Slavic people must be their slaves was especially virulent in regard to Russia. Erich Koch, the roughneck Reich Commissar for the Ukraine, expressed it in a speech at Kiev on March 5, 1945.

We are the Master Race and must govern hard but just ... I will draw the very last out of this country. I did not come to spread bliss ... The population must work, work, and work again [...] We are a master race, which must remember that the lowliest German worker is racially and biologically a thousand times more valuable than the population [of the Ukraine]. (emphasis added)

- ^ a b c Reichsführer-SS (1942). Der Untermensch "The subhuman". Berlin: SS Office. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ Snyder, T. (2011). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Vintage. pp. 144–5, 188. ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- ^ Mineau, André (2004). Operation Barbarossa: Ideology and Ethics Against Human Dignity. Amsterdam; New York: Rodopi. p. 180. ISBN 90-420-1633-7

- ^ <Simone Gigliotti, Berel Lang. The Holocaust: A Reader. Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Carlton, Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. p. 14

- ^ a b c

"Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe". Northeastern University. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Stoddard, Lothrop (1922). The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under Man. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Losurdo, Domenico (2004). "Toward a Critique of the Category of Totalitarianism" (PDF, 0.2 MB). Historical Materialism. 12 (2). Translated by Marella & Jon Morris. Brill: 25–55, here p. 50. doi:10.1163/1569206041551663. ISSN 1465-4466.

- ^ Rosenberg, Alfred (1930). Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts: Eine Wertung der seelischgeistigen Gestaltungskämpfe unserer Zeit [The Myth of the Twentieth Century] (in German). Munich: Hoheneichen-Verlag. p. 214.

- ^

Fontane, Theodor (1898). "Der Stechlin: 33. Kapitel". Der Stechlin [The Stechlin] (in German). ISBN 978-3-86640-258-4.

Jetzt hat man statt des wirklichen Menschen den sogenannten Übermenschen etabliert; eigentlich gibt es aber bloß noch Untermenschen, und mitunter sind es gerade die, die man durchaus zu einem ›Über‹ machen will. (Now one has established instead of the real human the so-called superhuman; but actually only subhumans are left, and sometimes they are the very ones that are tried to be declared as 'super'.)

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1882). "Kapitel 143: Größter Nutzen des Polytheismus". Die fröhliche Wissenschaft [The Gay Science] (in German). Vol. 3rd book. Chemnitz: Ernst Schmeitzner.

Die Erfindung von Göttern, Heroen und Übermenschen aller Art, sowie von Neben- und Untermenschen, von Zwergen, Feen, Zentauren, Satyrn, Dämonen und Teufeln war die unschätzbare Vorübung zur Rechtfertigung der Selbstsucht und Selbstherrlichkeit des einzelnen [...]. (The invention of gods, heroes, and overmen of all kinds, as well as near-men and undermen, of dwarfs, fairies, centaurs, satyrs, demons and devils was the inestimable preliminary exercise for the justification of the egoism and sovereignty of the individual [...]) [From the translation by Walter Kaufmann]

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^

Jean Paul (1795). "8. Hundposttag". Hesperus oder 45 Hundposttage (in German).

Obgleich Leute aus der großen und größten Welt, wie der Unter-Mensch, der Urangutang, im 25sten Jahre ausgelebt und ausgestorben haben – vielleicht sind deswegen die Könige in manchen Ländern schon im 14ten Jahre mündig –, so hatte doch Jenner sein Leben nicht so weit zurückdatiert und war wirklich älter als mancher Jüngling. (Although people from the great world and the greatest have, like the sub-man, the orang-outang, lived out and died out in their twenty-fifth year, — for which reason, perhaps, in many countries kings are placed under guardianship as early as their fourteenth, — nevertheless January had not ante-dated his life so far, and was really older than many a youth.) [From the translation by Charles T. Brooks]

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kampf dem Weltfeind", Stürmer publishing house, Nuremberg, 1938, 05/25/1927, speech in the Bavarian regional parliament, German: "Es war zur Zeit der Räteherrschaft. Als das losgelassene Untermenschentum mordend durch die Straßen zog, da versteckten sich Abgeordnete hinter einem Kamin im bayerischen Landtag."

- ^

Himmler, Heinrich (1936). Die Schutzstaffel als antibolschewistische Kampforganisation [The SS as an Anti-bolshevist Fighting Organization] (in German). Munich: Franz Eher Nachfolger.

Wir werden dafür sorgen, daß niemals mehr in Deutschland, dem Herzen Europas, von innen oder durch Emissäre von außen her die jüdisch-bolschewistische Revolution des Untermenschen entfacht werden kann.

- ^

Office of United States Chief of Counsel For Prosecution of Axis Criminality (1946). "Chapter XV: Criminality of Groups and Organizations – 5. Die Schutzstaffeln". Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression (PDF, 46.2 MB). Vol. Volume II. Washington, D.C.: USGPO. p. 220. OCLC 315871222.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^

Stein, Stuart D (8 January 1999). "The Schutzstaffeln (SS) – The Nuremberg Charges, Part I". Web Genocide Documentation Centre. University of the West of England. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Paul Meier-Benneckenstein, Deutsche Hochschule für Politik Titel: Dokumente der Deutschen Politik, Volume 4, Junker und Dünnhaupt Verlag, Berlin, 2. ed., 1937; speech held on 10 September 1936; In German: "... das Untermenschentum, das in jedem Volke als Hefe vorhanden ist ...".

- ^ Goebbels speech at the 1935 Nuremberg Rally

- ^ Quality of Life: The New Medical Dilemma, edited by James J. Walter, Thomas Anthony Shannon, page 63

- ^ Pelt, Robert-Jan van (January 1994). "Auschwitz: From Architect's Promise to Inmate's Perdition". Modernism/Modernity. 1 (1): 80–120, here p. 97. doi:10.1353/mod.1994.0013. ISSN 1071-6068.

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ Huer, Jon (2012). Call from the Cave: Our Cruel Nature and Quest for Power. Lanham, Maryland: Hamilton Books. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-7618-6015-0.

The Nazis considered any human being in the "east", usually the Slavs, as "sub-human", only fit for slavery to the Germans.

- ^ Sealing Their Fate (Large Print 16pt) by David Downing, page 49

- ^ Rees, L (1997) "The Nazis, a warning from history," BBC Books, P126

- ^ Mazower, M (2008) Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe, Penguin Press P197

- ^ Wegner, Bernt (1997) [1991]. From Peace to War: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the World, 1939-1941. Berghahn Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-57181-882-9.

- ^ Ceran, Tomasz (2015). The History of a Forgotten German Camp: Nazi Ideology and Genocide at Szmalcówka. I.B.Tauris. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-85773-553-9.

- ^ Hitler Youth, 1922–1945: An Illustrated History by Jean-Denis Lepage, page 91

- ^ Native Realm: A Search for Self Definition by Czeslaw Milosz, page 132

- ^ Richard J. Evans, In Hitler's Shadow (1999), pp. 59-60

- ^ Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History (2000), p. 512

- ^ "The Warsaw Ghetto: Himmler Orders the Destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto".

- ^ Yits?a? Arad; Yisrael Gutman; Abraham Margaliot (1999). Documents on the Holocaust: Selected Sources on the Destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland, and the Soviet Union. U of Nebraska Press. p. 292. ISBN 0-8032-1050-7.

- ^ According to Nazi policy the Croats were classified as more "Germanic than Slavic"; this was supported by Croatia's fascist dictator Ante Pavelić, who maintained that the Croatians were descendants of the ancient Goths and "had the Pan-Slav idea forced upon them as something artificial".

Rich, Norman (1974). Hitler's War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order, p. 276-7. W. W. Norton & Company Inc., New York. - ^ Norman Davies. Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Pp. 167, 209.

Further reading

- Lukas, Dr. Richard (1986). The Forgotten Holocaust: Poles Under Nazi Occupation 1939-1944. New York: University of Kentucky Press/Hippocrene Books,. ISBN 0-7818-0901-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

External links

- Der Untermensch propaganda poster published by the SS.

- Hitler's plans for Eastern Europe at archive.today (archived 2012-05-27)

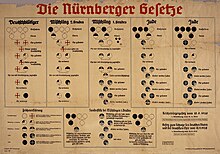

- "Die Drohung des Untermenschen" This is an example of the term "Untermensch" being used in the context of the Nazi eugenics programme. The table suggests that "inferior" people (unmarried and married criminals, parents whose children have learning disabilities) have more children than "superior" people (ordinary Germans, academics). Note that the heading is the subtitle of the German version of Lothrop Stoddard's book.

- Der Untermensch: the Nazi pamphlet