Marketing of electronic cigarettes

E-cigarette advertising is legal in some jurisdictions. A 2014 review said, "the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s."[3] In the US, six large e-cigarette businesses spent $59.3 million on promoting e-cigarettes in 2013.[4] The use of e-cigarettes has been increasing exponentially since 2004.[3][5]

E-cigarettes are marketed as a cheaper, more pleasant, and more convenient complement or alternative to smoking. E-cigarettes are also marketed to unwilling smokers as an alternative to quitting (see image).

Common, but problematic marketing claims are that

- e-cigarettes are harmless, or even beneficial, to the user[6]

- e-cigarettes are harmless to others breathing the same air[7]

- e-cigarettes help smokers quit (weak evidence)[8]

- e-cigarettes are only used by smokers

The evidence for these claims is weak to negative. Nonsmokers are more likely to start vaping if they think e-cigarettes are not very harmful or addictive; beliefs about harmfullness and addiction don't affect the probability that smokers will start vaping.[9]

As nicotine-containing products, e-cigarettes are highly addictive. Nicotine is addictive on a level comparable to heroin and cocaine.[10]

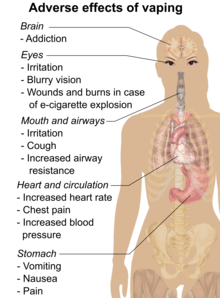

E-cigarettes and nicotine are regularly promoted as safe and beneficial in the media and on brand websites.[6] It is claimed, for instance, that e-cigarettes emit "only water vapor". E-cigarette vapor contains possibly harmful chemicals such as nicotine, carbonyls, heavy metals, and organic volatile compounds, in addition to particulates.[11] It is plausible that vapourizing cigarettes may be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes,[2] but there is evidence of short-term harm (see image) and no evidence on the long-term health effects, as e-cigarettes were introduced in 2004.

Branding is used to imply healthiness, with brands named "Safe-cigs", "Lung Buddy", "iBreathe", and "E-HealthCigs".[7]

E-cigarettes are falsely marketed as harmless to bystanders. Messages imply that users need no longer go outside to satisfy nicotine cravings.[12] Phrases such as "No second-hand smoke" and "No passive smoking" are also common.[7] Since the emissions of an e-cigarette are not classified by the marketer as smoke, but as vapour, this is technically true. However, the emissions are harmful to the health of people who are using or will use the same air. The World Health Organization's view regarding second hand aerosol (SHA) is "that while there are a limited number of studies in this area, it can be concluded that SHA is a new air contamination source for particulate matter, which includes fine and ultrafine particles, as well as 1,2-propanediol, some VOCs [volatile organic compounds], some heavy metals, and nicotine" and "[i]t is nevertheless reasonable to assume that the increased concentration of toxicants from SHA over background levels poses an increased risk for the health of all bystanders".[13] Public Health England has concluded that "international peer-reviewed evidence indicates that the risk to the health of bystanders from secondhand e-cigarette vapor is extremely low and insufficient to justify prohibiting e-cigarettes".[14] A systematic review concluded, "the absolute impact from passive exposure to EC [electronic cigarette] vapor has the potential to lead to adverse health effects. The risk from being passively exposed to EC vapor is likely to be less than the risk from passive exposure to conventional cigarette smoke."[15]

There is no evidence that the cigarette brands are selling e-cigarettes as part of a plan to phase out traditional cigarettes, despite some claiming to want to cooperate in "harm reduction".[3] There are concerns that e-cigarette use may delay and deter quitting, by giving users an excuse to keep using nicotine.[3][5] E-cigarettes have been marketed at a reason not to quit.[16] Only one study comparing e-cigarettes to standard quitting methods has been published.[8][5] Many jurisdictions have regulated e-cigarettes, but they have not won widespread medical approval as a smoking cessation aid, due to the lack of clinical evidence that they are effective.

There is evidence that people who have never smoked take up vaping.[17] Nonsmokers are more likely to start vaping if they think e-cigarettes are not very harmful or addictive; beliefs about harmfullness and addiction don't affect the probability that smokers will start vaping.[9] The World Health Organization is concerned about addiction of non-smokers.[2] Flavours, especially candy flavours, are thought to be used to appeal to minors, like earlier flavoured tobacco products (now commonly banned).[18][4]

E-cigarettes are aggressively promoted, mostly via the internet, as a healthy alternative to smoking in the US.[19] Easily circumvented age verification at company websites enables young people to access and be exposed to marketing for e-cigarettes.[20] E-cigarettes are marketed to young people[21] using cartoon characters and candy flavors,[22] in a re-use of older (now widely illegal) strategies used to promote chewing tobacco and cigarettes.[23] E-cigarettes are also widely marketed on social media, where age restrictions are often not implemented.[24][25][26]

Many other aspect of e-cigarette ads are familiar; like ads from the 1800 and 1900s, they show unrepresentatively healthy, well-dressed, high-status people. They may portray users as more sociable (the ad illustrated here actually asserts that breaking a nicotine addiction will cause you to be disliked). They are likely to imply that users of their product are behaving in an adult manner, making free choices, rebelling against coercive authority, and expressing their individuality; they are unlikely to mention nicotine addiction or other negative health effects. They offer alternatives to quitting for "concerned smokers", and claim that these alternatives are intelligent.[27]

Claims of healthiness are also made indirectly; for instance, a woman exhales into a baby carriage in a 2013 e-cigarette ad (for Flavor Vapes, UTVG, Inc.) reminiscent of early-twentieth-century cigarette ads.[28]

E-cigarettes are advertised as good for stress reduction, mood, and insomnia.[29] It is certainly true that nicotine products temporarily relieve nicotine withdrawal symptoms. The American Psychologist stated "Smokers often report that cigarettes help relieve feelings of stress. However, the stress levels of adult smokers are slightly higher than those of nonsmokers, adolescent smokers report increasing levels of stress as they develop regular patterns of smoking, and smoking cessation leads to reduced stress. Far from acting as an aid for mood control, nicotine dependency seems to exacerbate stress. This is confirmed in the daily mood patterns described by smokers, with normal moods during smoking and worsening moods between cigarettes. Thus, the apparent relaxant effect of smoking only reflects the reversal of the tension and irritability that develop during nicotine depletion. Dependent smokers need nicotine to remain feeling normal."[30]

E-cigarettes are also advertised as dieting aids. Nicotine may in fact be an appetite suppressant; however, getting addicted to nicotine in order to lose weight is widely discouraged by public health professionals.[31] There is much controversy concerning whether smokers are actually thinner than nonsmokers.[31] Some studies have shown that smokers—including long term and current smokers—weigh less than nonsmokers, and gain less weight over time.[32] Conversely, certain longitudinal studies have not shown correlation between weight loss and smoking.[33]

Celebrity endorsements are also used to encourage e-cigarette use.[34] A national US television advertising campaign starred Steven Dorff exhaling a "thick flume" of what the ad describes as "vapor, not tobacco smoke", exhorting smokers with the message "We are all adults here, it's time to take our freedom back."[35] The ads, in a context of longstanding prohibition of tobacco advertising on TV, were criticized by organizations such as Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids as undermining anti-tobacco efforts.[35] Cynthia Hallett of Americans for Non-Smokers' Rights described the US advertising campaign as attempting to "re-establish a norm that smoking is okay, that smoking is glamorous and acceptable".[35] University of Pennsylvania communications professor Joseph Cappella stated that the setting of the ad near an ocean was meant to suggest an association of clean air with the nicotine product.[35]

In 2016, e-cigarette companies fought not to have the health and safety of their products evaluated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, arguing that all existing products should be grandfathered in.[36]

Bans

While advertising of tobacco products is banned in most countries, fewer ban nicotine marketing.

E-cigarettes have been listed as drug delivery devices in several countries because they contain nicotine, and their advertising has been restricted until safety and efficacy clinical trials are conclusive.[37] Since they do not contain tobacco, television advertising in the US is not restricted.[38] Some countries have regulated e-cigarettes as a medical product even though they have not approved them as a smoking cessation aid.[39]

Television and radio e-cigarette advertising in some countries may be indirectly encouraging traditional cigarette smoking.[3]

In some jurisdictions, it is legal to market (and sell) e-cigarettes to minors.[4]

See also

References

- ^ Detailed reference list is located on a separate image page.

- ^ a b c WHO. "Electronic nicotine delivery systems" (PDF). pp. 1–13. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- ^ a b c "E-Cigarette use among children and young people: the need for regulation". Expert Rev Respir Med. 9: 1–3. 2015. doi:10.1586/17476348.2015.1077120. PMID 26290119.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c Kalkhoran, Sara; Glantz, Stanton A (2016). "E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 4: 116–128. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00521-4. PMC 4752870. PMID 26776875.

- ^ a b England, Lucinda J.; Bunnell, Rebecca E.; Pechacek, Terry F.; Tong, Van T.; McAfee, Tim A. (2015). "Nicotine and the Developing Human". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 49 (2): 286–93. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. ISSN 0749-3797. PMC 4594223. PMID 25794473.

- ^ a b c http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st387.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img17157.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt036.php&theme_name=Healthier&subtheme_name=Second%20Hand

- ^ a b Hartman-Boyce, Jamie; McRobbie, Hayden; al, et (2016). "Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD010216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub3. PMID 27622384.

- ^ a b https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29626778

- ^ "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Tobacco Control Program. California Department of Public Health. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fernández, Esteve; Ballbè, Montse; Sureda, Xisca; Fu, Marcela; Saltó, Esteve; Martínez-Sánchez, Jose M. (2015). "Particulate Matter from Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Cigarettes: a Systematic Review and Observational Study". Current Environmental Health Reports. 2: 423–9. doi:10.1007/s40572-015-0072-x. ISSN 2196-5412. PMID 26452675.

- ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st367.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img16976.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt039.php&theme_name=Social%20Appeal&subtheme_name=Socializing

- ^ WHO (August 2016). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Electronic Non-Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS/ENNDS)" (PDF). pp. 1–11.

- ^ Public Health England. "E-cigarettes in public places and workplaces: a 5-point guide to policy making". uk.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Hess, IM; Lachireddy, K; Capon, A (15 April 2016). "A systematic review of the health risks from passive exposure to electronic cigarette vapour". Public health research & practice. 26 (2). doi:10.17061/phrp2621617. PMID 27734060.

- ^ see image in article, File:No-one_likes_a_quitter,_e-cigarette_ad.jpg

- ^ https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm499234.htm

- ^ Laura Bach, "FLAVORED TOBACCO PRODUCTS ATTRACT KIDS", Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, (April. 2017)

- ^ Rom, Oren; Pecorelli, Alessandra; Valacchi, Giuseppe; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2014). "Are E-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1340 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 25557889.

- ^ ""Smoking revolution": a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites". Am J Prev Med. 46 (4): 395–403. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. PMC 3989286. PMID 24650842.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "E-cigarettes and Lung Health". American Lung Association. 2015.

- ^ "Myths and Facts About E-cigarettes". American Lung Association. 2015.

- ^ http://adage.com/article/media/big-tobacco-spending-ads-e-cigarettes/241993/

- ^ April 5, Ashley Welch CBS News; 2018; Pm, 5:02. "Facebook is used to promote tobacco, despite policies against it, study finds". Retrieved 2018-05-18.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Affairs, By Amy Jeter Hansen Amy Jeter Hansen is a digital media specialist for the medical school's Office of Communication & Public. "Tobacco products promoted on Facebook despite policies". News Center. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ Hansen, Author Amy Jeter (2018-04-05). "Despite policies, tobacco products marketed on Facebook, Stanford researchers find". Scope. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st437.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img21854.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt053.php&theme_name=Smart,%20Pure%20&%20Fresh&subtheme_name=Smarter

- ^ A woman exhales from an e-cigarette into a baby carriage in this 2013 e-cigarette ad for Flavor Vapes (UTVG, Inc.)

- ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st508.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img21920.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt065.php&theme_name=Health%20Giving&subtheme_name=Calming

- ^ Parrott AC (Oct 1999). "Does cigarette smoking cause stress?". The American Psychologist. 54 (10): 817–820. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.817. PMID 10540594.

- ^ a b Chiolero, A; Faeh, D; Paccaud, F; Cornuz, J (Apr 2008). "Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (4): 801–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. PMID 18400700.

- ^ Albanes, Demetrius, D. Yvonne Jones, Marc Micozzi, and Margaret E. Mattson, “Associations between Smoking and Body Weight in the US Population: Analysis of NHANES II,” American Journal of Public Health 77.4 (1987)

- ^ Nichter, Mimi, Mark Nichter, Nancy Vuckovic, laura Tesler, Shelly Adrian, and Cheryl Ritenbaugh, “Smoking as a Weight-Control Strategy among Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Reconsideration,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 18.3 (2004): 307

- ^ Linda Bauld; Kathryn Angus; Marisa de Andrade (May 2014). "E-cigarette uptake and marketing" (PDF). Public Health England. pp. 1–19.

- ^ a b c d Daniel Nasaw (5 December 2012). "Electronic cigarettes challenge anti-smoking efforts". BBC News.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/03/us/politics/e-cigarettes-vaping-cigars-fda-altria.html

- ^ Cervellin, Gianfranco; Borghi, Loris; Mattiuzzi, Camilla; Meschi, Tiziana; Favaloro, Emmanuel; Lippi, Giuseppe (2013). "E-Cigarettes and Cardiovascular Risk: Beyond Science and Mysticism". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 40 (01): 060–065. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1363468. ISSN 0094-6176. PMID 24343348.

- ^ Maloney, Erin K.; Cappella, Joseph N. (2015). "Does Vaping in E-Cigarette Advertisements Affect Tobacco Smoking Urge, Intentions, and Perceptions in Daily, Intermittent, and Former Smokers?". Health Communication. 31: 1–10. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.993496. ISSN 1041-0236. PMID 25758192.

- ^ Bekki, Kanae; Uchiyama, Shigehisa; Ohta, Kazushi; Inaba, Yohei; Nakagome, Hideki; Kunugita, Naoki (2014). "Carbonyl Compounds Generated from Electronic Cigarettes". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (11): 11192–11200. doi:10.3390/ijerph111111192. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4245608. PMID 25353061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)