Toda people

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

Toda woman, 1909 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,002 (2011 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Toda |

Toda people are a Dravidian ethnic group who live in the Nilgiri Mountains of Tamil Nadu. Before the 18th century and British colonisation, the Toda coexisted locally with other ethnic communities, including the Kota, Badaga and Kurumba, in a loose caste-like society, in which the Toda were the top ranking.[2] During the 20th century, the Toda population has hovered in the range 700 to 900.[2] Although an insignificant fraction of the large population of India, since the early 19th century the Toda have attracted "a most disproportionate amount of attention because of their ethnological aberrancy"[2] and "their unlikeness to their neighbours in appearance, manners, and customs."[2] The study of their culture by anthropologists and linguists proved significant in developing the fields of social anthropology and ethnomusicology.

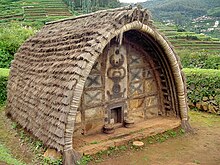

The Toda traditionally live in settlements called mund, consisting of three to seven small thatched houses, constructed in the shape of half-barrels and located across the slopes of the pasture, on which they keep domestic buffalo.[3] Their economy was pastoral, based on the buffalo, which dairy products they traded with neighbouring peoples of the Nilgiri Hills.[3] Toda religion features the sacred buffalo; consequently, rituals are performed for all dairy activities as well as for the ordination of dairymen-priests. The religious and funerary rites provide the social context in which complex poetic songs about the cult of the buffalo are composed and chanted.[3]

Fraternal polyandry in traditional Toda society was fairly common; however, this practice has now been totally abandoned, as has female infanticide. During the last quarter of the 20th century, some Toda pasture land was lost due to outsiders using it for agriculture[3] or afforestation by the State Government of Tamil Nadu. This has threatened to undermine Toda culture by greatly diminishing the buffalo herds. Since the early 21st century, Toda society and culture have been the focus of an international effort at culturally sensitive environmental restoration.[4] The Toda lands are now a part of The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO-designated International Biosphere Reserve; their territory is declared UNESCO World Heritage Site.[5]

Population

According to M. B. Emeneau in 1984, the successive decennial Census of India figures for the Toda are: 1871 (693), 1881 (675), 1891 (739), 1901 (807), 1911 (676) (corrected from 748), 1951 (879), 1961 (759), 1971 (812). In his judgment, these records

"justif[y] [sic] concluding that a figure between 700 and 800 is likely to be near the norm, and that variation in either direction is due on the one hand to epidemic disaster and slow recovery thereafter (1921 (640), 1931 (597), 1941 (630)) or on the other hand to an excess of double enumeration (suggested already by census officers for 1901 and 1911, and possibly for 1951). Another factor in the uncertainty in the figures is the declared or undeclared inclusion or exclusion of Christian Todas by the various enumerators ... Giving a figure between 700 and 800 is highly impressionistic, and may for the immediate present and future be pessimistic, since public health efforts applied to the community seem to be resulting in an increased birth rate and consequently, one would expect, in an increased population figure. However, earlier predictions that the community was declining were overly pessimistic and probably never well-founded."[2]

Physical anthropology

Physical anthropologist Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt firstly described the Todas as being South Indid, therefore connecting them to ancient Proto Dravidian population.[6] DNA studies in the early 21st century showed that the Toda and Kota share genes which distinguish them from the other Nilgiri Hill Tribes.[7]

Culture and society

The Toda are most closely related to the Kota both ethnically and linguistically.

Clothing

The Toda dress consists of a single piece of cloth, which is worn like shalya wrap over a dhoti for men and as a skirt for women along with shalya wrap.

Economy

Their sole occupation is cattle-herding and dairy-work. Holy dairies are built to store the buffalo milk.

Marriage

They once practised fraternal polyandry, a practice in which a woman marries all the brothers of a family, but no longer do so.[8][9] All the children of such marriages were deemed to descend from the eldest brother. The ratio of females to males is about three to five. The culture historically practised female infanticide. In the Toda tribe, families arrange contracted child marriage for couples.

Houses

The Todas live in small hamlets called munds. The Toda huts, called dogles, are of an oval, pent-shaped construction. They are usually 10 feet (3 m) high, 18 feet (5.5 m) long and 9 feet (2.7 m) wide. They are built of bamboo fastened with rattan and are thatched. Thicker bamboo canes are arched to give the hut its basic bent shape. Thinner bamboo canes (rattan) are tied close and parallel to each other over this frame. Dried grass is stacked over this as thatch. Each hut is enclosed within a wall of loose stones.

The front and back of the hut are usually made of dressed stones (mostly granite). The hut has a tiny entrance at the front – about 3 feet (90 cm) wide, 3 feet (90 cm) tall, through which people must crawl to enter the interior. This unusually small entrance is a means of protection from wild animals. The front portion of the hut is decorated with the Toda art forms, a kind of rock mural painting.

Food

The Todas are vegetarians and do not eat meat, eggs that can hatch, or fish (although some villagers do eat fish). The buffalo were milked in a holy dairy, where the priest/milkman also processed their gifts. Buffalo milk is used in a variety of forms: butter, butter milk, yogurt, cheese and drunk plain. Rice is a staple, eaten with dairy products and curries.

Religion

According to the Todas, the goddess Teikirshy and her brother first created the sacred buffalo and then the first Toda man. The first Toda woman was created from the right rib of the first Toda man. Many rites feature the buffalo,its milk and other products form the basis of their diet.

The Toda religion exalted high-class men as holy milkmen, giving them sacred status as priests of the holy dairy. According to Sir James Frazer in 1922 (see quote below from Golden Bough), the holy milkman was prohibited from walking across bridges while in office. He had to ford rivers by foot, or by swimming. The people are prohibited from wearing shoes or any type of foot covering.

Toda temples are constructed in a circular pit lined with stones. They are similar in appearance and construction to Toda huts. Women are not allowed to enter or go close to these huts that are designated as temples.

From Frazer's Golden Bough, 1922:

"Among the Todas of Southern India the holy milkman, who acts as priest of the sacred dairy, is subject to a variety of irksome and burdensome restrictions during the whole time of his incumbency, which may last many years. Thus he must live at the sacred dairy and may never visit his home or any ordinary village. He must be celibate; if he is married he must leave his wife. On no account may any ordinary person touch the holy milkman or the holy dairy; such a touch would so defile his holiness that he would forfeit his office. It is only on two days a week, namely Mondays and Thursdays, that a mere layman may even approach the milkman; on other days if he has any business with him, he must stand at a distance (some say a quarter of a mile) and shout his message across the intervening space. Further, the holy milkman never cuts his hair or pares his nails so long as he holds office; he never crosses a river by a bridge, but wades through a ford and only certain fords; if a death occurs in his clan, he may not attend any of the funeral ceremonies, unless he first resigns his office and descends from the exalted rank of milkman to that of a mere common mortal. Indeed it appears that in old days he had to resign the seals, or rather the pails, of office whenever any member of his clan departed this life. However, these heavy restraints are laid in their entirety only on milkmen of the very highest class".

Language

The Toda language is a member of the Dravidian family. The language is typologically aberrant and phonologically difficult. Linguists have classified Toda (along with its neighbour Kota) as a member of the southern subgroup of the historical family proto-South-Dravidian. It split off from South Dravidian, after Kannada and Telugu, but before Malayalam. In modern linguistic terms, the aberration of Toda results from a disproportionately high number of syntactic and morphological rules, of both early and recent derivation, which are not found in the other South Dravidian languages (save Kota, to a small extent.)[2]

Culture

The forced interaction with other peoples with technology has caused a lot of changes in the lifestyle of the Toda. They used to be primarily a pastoral people but now, they are increasingly venturing into agriculture and other occupations. They used to be strict vegetarians but now, some people eat meat.

Although many Toda abandoned their traditional distinctive huts for houses made of concrete,[8] in the early 21st century, a movement developed to build the traditional barrel-vaulted huts. From 1995 to 2005, forty new huts were built in this style, and many Toda sacred dairies were renovated. Each has a narrow stone pit around it and the tiny door is held shut with a heavy stone. Only the priest may enter it. It is used for storage of sacred buffalo milk.[10]

Embroidery

Registrar of Geographical Indication gave GI status for this unique embroidery, a practice which has been passed on to generations. The status ensures uniform pricing for Toda embroidery products and provides protection against low-quality duplication of the art.[11]

Notes

- ^ "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f (Emeneau 1984, pp. 1–2)

- ^ a b c d "Toda", Encyclopædia Britannica. (2007

- ^ Chhabra 2006

- ^ World Heritage sites, Tentative lists, April 2007. Whc.unesco.org (27 June 2013) in 2012.

- ^ Eickstedt, E. "Anthropologische Forschungen in Südindien". Anthropologischer Anzeiger (6): 64–85.

- ^ Vishwanathan, H.; et al. (December 2003). "Insertions/Deletions Polymorphism in Tribal Populations of Southern India and their possible Evolutionary Implications". Human Biology. 75 (6).

- ^ a b (Walker 2004)

- ^ (Walker 1998)

- ^ (Chhabra 2005) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChhabra2005 (help) Quote: "... over the past ten years, we have approached government and private agencies for sponsoring traditional houses. Today, we have been able to assist in funding over forty barrel-vaulted houses. Added to these are the scores of existing temples – two are conical and the rest barrel-vaulted."

- ^ "GI certificate for Toda embroidery formally handed over to tribals", The Hindu (15 June 2013).

References

- Classic Ethnographies

- Marshall, William E. (1873), Travels amongst the Toda, or the study of a primitive tribe in South India, London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Pp. xx, 269.

- Rivers, W. H. R. (1906), The Todas, London: Mcmillan and Company. Pp. xviii, 755.

- Thurston, Edgar; K. Rangachari (1909). Castes and Tribes of Southern India, Volume 7. Madras: Government Press.

- Walker, Anthony R. (1986). The Toda of South India: A New Look. Delhi: Hindustan Publishing Corp.

- Toda Music, Linguistics, Ethnomusicology

- Emeneau, M. B. (1958), "Oral Poets of South India: Todas", Journal of American Folklore, 71 (281): 312–324, doi:10.2307/538564, JSTOR 538564

- Emeneau, M. B. (1971), Toda Songs, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pp. xvii, 1003.

- Hockings, Paul, "Reviewed Work(s): Toda Songs, by M. B. Emeneau", The Journal of Asian Studies, 31 (2): 446, doi:10.2307/2052652, JSTOR 2052652

- Emeneau, Murray B. (1974), Ritual Structure and Language Structure of the Todas, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, Pp. 103, ISBN 0-87169-646-0.

- Tyler, Stephen A. (1975), "Reviewed Work(s): Ritual Structure and Language Structure of the Todas by M. B. Emeneau", American Anthropologist, 77 (4): 758–759, doi:10.1525/aa.1975.77.4.02a00930, JSTOR 674878.

- Emeneau, Murray B. (1984), Toda Grammar and Texts, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, Pp. xiii, 410, index (16), ISBN 0-87169-155-8.

- Nara, Tsuyoshi and Bhaskararao, Peri. 2003. Songs of the Toda. Osaka : ELPR Series A3-011.91pp [+3CDs with sound files of the songs].

- Nettl, Bruno; Bohlman, Phillip Vilas (1991), Comparative Musicology and Anthropology of Music: Essays on the History of Ethnomusicology, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, Pp. 396, pp. 438–449, ISBN 0-226-57409-1.

- Shalev, M. Ladefoged, P. and Bhaskararao, P. 1994. "Phonetics of Toda." PILC Journal of Dravidic Studies, 4:1. 19-56pp. (Earlier version in: University of California Working Papers in Phonetics. 84. 89-126 pp.). 1993.

- Spajic', S. Ladefoged, P. and Bhaskararao, P. 1996. "The Trills of Toda." Journal of International Phonetic Association, 26:1. 1-22pp.

- Modern Anthropology, Sociology, History

- Walker, Anthony (1998), Between Tradition and Modernity, and Other Essays on the Toda of South India, Delhi: B. R. Publishing Corporation.

- Emeneau, M. B. (1988), "A Century of Toda Studies: Review of 'The Toda of South India: A New Look' by Anthony R. Walker; M. N. Srinivas", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 108 (4): 605–609, doi:10.2307/603148, JSTOR 603148.

- Sutton, Deborah (2003), "'In this the land of the Todas': Imaginary Landscapes and Colonial Policy in Nineteenth-Century Southern India", in Dorrian, M.; Rose, G. (eds.), Deterritorialisations, Revisioning Landscape and Politics, London: Black Dog Press.

- Sutton, Deborah (2002), "'Horrid Sights and Customary Rights': The Toda Funeral on the Colonial Nilgiris", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 39 (1): 45–70, doi:10.1177/001946460203900102.

- Walker, Anthony R. (2004), "The Truth About The Toda", Frontline, The Hindu, archived from the original on 13 October 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help).

- Toda Traditional Knowledge, Environment, and Modern Science

- From: Chhabra, Tarun. 15 August 2002. "Toda's Traditions In Peril", Down to Earth. Quote:

Toda’s quaint barrel vaulted houses, which symbolise the Nilgiris, are today hard to spot. These images have been dry transferred on T-shirts and other products as logos. Seven years ago, there were just a couple of traditional houses remaining in the permanent hamlets. One day, a Toda wanted to build a traditional house for his ailing father. The administration agreed to provide the funds. Quite soon, it was ready and one Sunday morning, the Collector, additional Collector and the Superintendent of police inaugurated the house. The construction was so impressive that advances were paid on the spot for two more houses. Nine houses came up that year. Today, over 35 traditional houses have been constructed.

- Chhabra, Tarun (2005), "How Traditional Ecological Knowledge addresses Global Climate change: the perspective of the Todas - the indigenous people of the Nilgiri hills of South India" (PDF), Proceedings of the Earth in Transition: First World Conference, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2012

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - The Society for Ecological Restoration and Indigenous Peoples' Restoration Network. EIT PROJECT SHOWCASE: The Edhkwehlynawd Botanical Refuge (EBR)

- Chhabra, Tarun (2005), "How Traditional Ecological Knowledge addresses Global Climate change: the perspective of the Todas - the indigenous people of the Nilgiri hills of South India" (PDF), Proceedings of the Earth in Transition: First World Conference (ppt), archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help).(Pictures of a new house being built on pages 57–60, and new house, with decorative art, being blessed on page 70) - Chhabra, Tarun (2006), "Restoring the Toda Landscapes of the Nilgiri Hills in South India", Plant Talk, 44, archived from the original on 10 October 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - India Environmental Trust. 2005. Supported Projects: Edhkwehlynawd Botanical Refuge (EBR) - Reforestation in a Tribal Area

- National Committee for the Netherlands for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN-NL). 2006. Funded Projects:, India: Nilgiri Hills, NGO (EBR), 8 Hectares.

- Rajan, S.; Sethuraman, M.; Mukherjii, Pulok K. (2002), "Ethnobiology of the Nilgiri Hills, India", Phytotherapy Research, 16 (2): 98–116, doi:10.1002/ptr.1098.

External links

- The Society for Ecological Restoration and Indigenous Peoples' Restoration Network. EIT PROJECT SHOWCASE: The Edhkwehlynawd Botanical Refuge (EBR)

- India Environmental Trust. 2005. Supported Projects: Edhkwehlynawd Botanical Refuge (EBR) - Reforestation in a Tribal Area

- National Committee for the Netherlands for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN-NL). 2006. Funded Projects:, India: Nilgiri Hills, NGO (EBR), 8 Hectares.

- Toasting the Todas — 2008. Travelogue with pictures of ceremonies.

- Ethnologue: Toda, A language of India

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Todas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1044.