Congregationalism in the United States

Congregationalism in the United States is a denominational family of Congregational churches distinguished by having a congregational form of church government and who trace their origins mainly to Puritan settlers of colonial New England. Congregational churches have had an important impact on the political, religious and cultural history of the United States. Their practices concerning church governance influenced the early development of democratic institutions in New England, and many of the nation's oldest educational institutions, such as Harvard and Yale University, were founded to train Congregational clergy. In the 21st century, the Congregational tradition is represented by the United Church of Christ, the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches, and the Conservative Congregational Christian Conference.

History

Early settlement of New England (1630–1640)

The Congregational tradition was brought to America in the 1630s by the Puritans—a Calvinistic group within the Church of England that desired to purify it of any remaining teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church.[1] As part of their reforms, Puritans desired to replace the Church of England's episcopal polity with another form of church government. Some English Puritans favored presbyterian polity (such as was utilized by the Church of Scotland), but those who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony organized their churches along congregational lines.[2]

Developing the New England Way

According to historian James F. Cooper, Jr., Congregationalism helped imbue the political culture of Massachusetts with several important concepts: "adherence to fundamental or 'higher' laws, strict limitations upon all human authority, free consent, local self-government, and, especially, extensive lay participation."[3] However, congregational polity also meant the absence of any centralized church authority. The result was that at times the first generation of Congregationalists struggled to agree on common beliefs and practices. For example, specific rules on church membership and baptism requirements were still being debated into the late 1630s.[3]

To help achieve unity, Puritan clergy would often meet in conferences to discuss issues arising within the churches and to offer advice. Congregationalists also looked to the ministers of the First Church in Boston to set examples for other churches to follow. One of the most prominent of these ministers was John Cotton, considered by historians to be the "father of New England Congregationalism", who through his preaching helped to standardize Congregational practices. Because of these efforts at promoting unity, standardization of practices related to baptism, church discipline, and election of church officers was largely achieved by 1635.[4]

Within the first decade, the colonists developed a system in which each community organized a gathered church of believers (i.e. only those who were thought to be among the elect and could give an account of a conversion experience were admitted as members).[5] Every congregation was founded upon a church covenant, a written agreement signed by all members in which they agreed to uphold congregational principles, to be guided by sola scriptura in their decision making, and to submit to church discipline. The right of each congregation to elect its own officers and manage its own affairs was upheld.[6][7]

For church offices, Congregationalists imitated the model developed in Calvinist Geneva. There were two major offices: elder (or presbyter) and deacon. There were two types of elders. Ministers, whose responsibilities included preaching and administering the sacraments, were referred to as teaching elders. Prominent laymen would be elected as ruling elders. Ruling elders governed the church alongside teaching elders, and, while they could not administer the sacraments, they could preach. Ruling elders were chosen for life. The duties of deacons largely revolved around financial matters. Other than elders and deacons, congregations also elected messengers to represent them in synods (church councils) for the purpose of offering non-binding advisory opinions.[8]

The Puritans had created a society in which Congregationalism was the state church, its ministers were supported by tax payers, and only full church members could vote in elections.[9] To ensure that the colony had a supply of educated ministers, Harvard University was founded in 1636.[10] By 1640, 18 churches had been gathered in Massachusetts.[11] In addition, Puritans established the Connecticut Colony in 1636 and New Haven Colony in 1637.[12] Altogether, there were 33 Congregational churches in New England.[13]

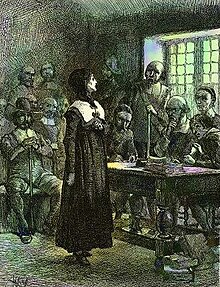

Antinomian Controversy

The major conflict during the settlement period was the Antinomian Controversy of 1636–1638. In 1635, Anne Hutchinson began holding meetings in her home to summarize the previous week's sermons for women who had been absent. Soon dozens of women and men were attending her meetings, including the colony's governor, Henry Vane. Such gatherings were not unusual. Hutchinson, however, became critical of ministers who taught the doctrine of "preparation", the idea that a person could prepare for salvation by attending church, reading the Bible, and living a moral life. Preparationist ministers did not teach that such actions merited salvation, only that they helped a sinner to prepare for receiving God's grace.[14] In contrast to the free grace theology of John Cotton, who she greatly admired, Hutchinson accused preparationist ministers of legalism and preaching a "covenant of works" rather than a "covenant of grace".[15]

By the fall of 1636, Hutchinson's support in Boston was growing. Eventually, she won over nearly the entire Boston congregation, which nearly censured its own pastor, John Wilson, for opposing the free grace position. Hutchinson also had the apparent support of Cotton and Boston's two ruling elders.[16] Outside of Boston, the elders of Massachusetts and the Connecticut and New Haven colonies unanimously rejected Hutchinson's teachings as Antinomianism. They finally prevailed upon Cotton to speak out against the errors of the Antinomians at a synod in September 1637. A civil trial was held in November in which Hutchinson was sentenced to banishment, and a church trial followed in March 1638 in which the Boston congregation switched sides and unanimously voted for Hutchinson's excommunication. This effectively ended the controversy.[17]

In the aftermath of the crisis, ministers realized the need for greater communication between churches and standardization of preaching. As a consequence, nonbinding ministerial conferences to discuss theological questions and address conflicts became more frequent in the following years.[18] A more substantial innovation was the implementation of the "third way of communion", a method of isolating a dissident or heretical church from neighboring churches. Members of an offending church would be unable to worship or receive the Lord's Supper in other churches.[19]

Defining Congregationalism (1640s)

In the 1640s, Congregationalists were under pressure to craft a formal statement of congregational church discipline. This was partly motivated by the need to reassure English Puritans about congregational government. It was feared that the English Parliament might intervene in New England's churches due to dissatisfaction with their admission policies.[20] It was also thought necessary to combat the threat of Presbyterianism at home. Conflict erupted in the churches at Newbury and Hingham when their pastors began introducing presbyterian governance.[21]

The Massachusetts General Court called for a synod to meet in Cambridge to craft such a statement. The Cambridge Platform was completed by the synod in 1648 and commended by the General Court as an accurate description of Congregational practice after the churches were given time to study the document, provide feedback, and finally ratify it. While the Platform was legally nonbinding and intended only to be descriptive, it soon became regarded by ministers and lay people alike as the religious constitution of Massachusetts, guaranteeing the rights of church officers and members.[22]

Missionary efforts among the Native Americans began in the 1640s. John Eliot began missionary work among the natives in 1646 and later published the Eliot Indian Bible, a Massachusett language translation. The Mayhew family began their work among the natives of Martha's Vineyard around the same time as Eliot. These missionary efforts suffered serious setbacks as a result of King Philip's War.[23]

Puritan declension (1650–1691)

In the years after the Antinomian Controversy, Congregationalists struggled with the problem of decreasing conversions among second-generation settlers. These unconverted adults had been baptized as infants and most of them studied the Bible, attended church and raised their children as Christians, but they were barred from receiving the Lord's Supper, voting or holding office, and from having their children (the grandchildren of full members) baptized. As the number of unconverted adults grew, church leaders began to think of alternative ways of tying people to the church without abandoning the idea that the church should be one of believers.[24]

As early as 1648, some ministers proposed what would later become known as the Half-Way Covenant. This would allow the grandchildren of full members to be baptized as long as their parents accepted their congregation's covenant and lived Christian lives. Richard Mather and Thomas Shepard were early supporters of the change. In 1657, a meeting of ministers at Boston formally endorsed the Half-Way Covenant. In 1662, a synod of lay and clerical representatives also endorsed the Half-Way Covenant.[25]

Nevertheless, the decision to accept or reject the Half-Way Covenant belonged to each congregation. Some churches maintained the original standard into the 1700s. Other churches went beyond the Half-Way Covenant, opening baptism to all infants whether or not their parents or grandparents had been baptized. Other churches, citing the belief that baptism and the Lord's Supper were "converting ordinances" capable of helping the unconverted achieve salvation, allowed the unconverted to receive the Lord's Supper as well.[26]

The decline of conversions and the division over the Half-Way Covenant were part of a larger loss of confidence experienced by Puritans in the latter half of the 17th century. In the 1660s and 1670s, Puritans began noting signs of moral decline in New England, and ministers began preaching jeremiads calling people to account for their sins. The most popular jeremiad, Michael Wigglesworth's "The Day of Doom", became the first best seller in America.[27]

In 1684, Massachusetts' colonial charter was revoked. It was merged with the other Bible Commonwealths along with New York and New Jersey into the Dominion of New England. Edmund Andros, an Anglican, was appointed royal governor and demanded that Anglicans be allowed to worship freely in Boston. The Dominion collapsed after the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89, and a new charter was granted in 1691. However, the power of the Congregational churches remained diminished. The governor continued to be appointed by the crown, and voting rights were now based on wealth rather than church membership.[28]

Development of consociationalism (1690–1708)

In the 18th century, Congregational ministers began forming clerical associations for fellowship and consultation.[29] The first association was the Cambridge Association formed in 1690 for ministers in and around Boston. It met in Cambridge on the grounds of Harvard. Its purpose was to "debate any matter referring to ourselves" and "to hear and consider any cases that shall be proposed unto us, from churches or private persons". By 1692, two other associations had been formed, and the number had increased to five by 1705.[30]

In the 1690s, John Leverett the Younger, William Brattle (pastor of First Parish in Cambridge), Thomas Brattle, and Ebenezer Pemberton (pastor of Old South Church) proposed a number of changes in Congregational practice. These changes included abandoning the consideration of conversion narratives in granting church membership and allowing all baptized members of a community (whether full members or not) to vote in elections for ministers. They also supported the baptism of all children presented by any Christian sponsor and the liturgical use of the Lord's Prayer.[31]

These changes were strongly opposed by Increase Mather, president of Harvard. The result was that Thomas Brattle and his associates built a new church in Boston in 1698. They invited Benjamin Colman, then in England, to become the pastor. Coleman was ordained by Presbyterians in England before leaving for America because it was assumed that the conservative churches of Boston would have opposed his ordination in New England. After arriving in November 1699, his manner of ordination was controversial given that it had not been done by the congregation he was to serve, as was Congregational practice. Brattle Street Church was organized on December 12, 1699, but without the support of the other churches in the colony. Despite the opposition of Mather and other conservatives, however, the church gained recognition and in time it became indistinguishable from other Congregational churches.[32]

Ultimately, the formation of Brattle Street Church spurred Congregationalists to modify their polity and strengthen the role of associations in order to promote greater uniformity. Representatives from the Massachusetts ministerial associations met in Boston in September 1705. They proposed a plan with two major features. The first was that associations examine and license ministerial candidates, investigate charges of ministerial misconduct, and annually elect delegates to a colony-wide general association. The second feature was the creation of "standing councils" of ministers and lay representatives to supervise the churches within a geographical area and to act as counterparts to the ministerial associations. The decisions of these councils were to be "final and decisive" but could be referred to a neighboring standing council for further review. If a church refused to adhere to a council's ruling, the neighboring churches would withdraw communion from the offending church. In Massachusetts, the proposals encountered much opposition as they were viewed as being inconsistent with congregational polity. The creation of standing councils was never acted on, but Massachusetts associations did adopt a system of ministerial licensure.[33]

While largely rejected in Massachusetts, the proposals of 1705 received a more favorable reception in Connecticut. In September 1708, a synod met at the request of the Connecticut General Assembly to write a new platform of church government. The Saybrook Platform called for the creation of standing councils called consociations in every county and tasked associations with providing ministerial consultation and licensure. The platform was approved by the General Assembly and associations and consociations were formed in every county. The General Association of Connecticut was formed and met for the first time in May 1709. The Saybrook Platform was legally recognized until 1784 and continued to govern the majority of Connecticut churches until the middle of the 19th century.[34]

Yale University was established by the Congregational clergy of Connecticut in 1701.[35]

Great Awakening (1735–1744)

By the beginning of the 18th century, many believed that New England had become a morally degenerate society more focused on worldly gain than on religious piety. Church historian Williston Walker described New England piety of the time as "low and unemotional."[37] To spiritually awaken their congregations and rescue the original Puritan mission of creating a godly society, Congregational ministers promoted revivalism, the attempt to bring spiritual renewal to an entire community.[29] The first two decades of the 18th century saw local revivals occur that resulted in large numbers of converts. These revivals sometimes resulted from natural disasters that were interpreted as divine judgment.[38] For example, revival followed after the earthquake of October 29, 1727.[39]

In 1735, Jonathan Edwards led his First Church congregation of Northampton, Massachusetts, through a religious revival. His Narrative of Surprising Conversions, describing the conversion experiences that occurred in the revival, was widely read throughout New England and raised hopes among Congregationalists of a general revival of religion.[38]

These hopes were seemingly fulfilled with the start of the Great Awakening, which was initiated by the preaching of George Whitefield, an Anglican priest who had preached revivalistic sermons to large audiences in England. He arrived at Boston in September 1740, preaching first at Brattle Street Church, and then visited other parts of New England. Though only in New England for a few weeks, the the revival spread to every part of the region in the two years following his brief tour. Whitefield was followed by itinerant preacher and Presbyterian minister Gilbert Tennent and dozens of other itinerants.[40]

Initially, the Awakening's strongest supporters came from Congregational ministers, who had already been working to foster revivals in their parishes. Itinerants and local pastors worked together to produce and nourish revivals, and often local pastors would cooperate together to lead revivals in neighboring parishes. The most famous sermon preached during the Great Awakening, for example, was "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" delivered by Edwards at Enfield, Connecticut, in July 1741. Many in the congregation were affected by Edwards' sermon with minister Stephen Williams reporting "amazing shrieks and cries" caused by the heightened religious excitement.[41]

By 1742, the revival had entered a more radical and disruptive phase. Lay people became more active participants in the services by crying out, exhorting, or having visions. Uneducated men and women began to preach without formal training, and some itinerant preachers were active in parishes without the approval of the local pastor. Enthusiasts even claimed that many of the clergy were unconverted themselves and thus unqualified to be ministers.[42] Congregationalists split into Old Lights and New Lights over the Awakening, with Old Lights opposing it and New Lights supporting it.[43]

A notable example of revival radicalism was James Davenport, a Congregational minister who preached to large crowds throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut. Davenport denounced ministers who opposed him as being "unconverted" and "leading their people blindfold to hell." In March 1743, he held a book burning of the works of Increase Mather, William Beveridge, John Flavel and others.[44]

Concerns over the revival led the Connecticut General Assembly to call a synod in 1741, which was the last Congregational synod convened under state authority. This "General Consociation" consisted of both lay and clerical representatives from all of the consociations in the colony. It ruled that itinerant ministers should preach in no parish except with the permission of the local pastor. In May 1742, the General Assembly passed legislation requiring ministers to receive permission to preach from the local pastor; violation of the law would result in loss of his state-provided salary.[45] In 1743, the annual Massachusetts Ministerial Convention condemned "the disorderly tumults and indecent behaviors" that occurred in many revival meetings. Charles Chauncy of Boston's First Church became the leader of the revival's opponents with the publication of his Seasonable Thoughts on the State of Religion in New England, which attacked the enthusiasm and extravagant behaviors of revival meetings.[36]

Other Congregationalists met at Boston in 1743 under the leadership of Benjamin Colman of Brattle Street Church and Thomas Prince of Old South Church. They issued a resolution supporting the revival as the work of God and downplaying the impact of "irregularities" that had occurred.[36] Nevertheless, the atmosphere toward revival had changed by 1744 when Whitefield returned to New England. The faculties of Harvard and Yale issued statements critical of his methods, and ministerial associations throughout the region spoke against allowing him to preach in their churches.[46]

There were still those in New England who embraced the radical wing of the Awakening–with its trances, visions, and shouting. When radical revivalists could not control their local churches, they separated from the state churches and formed new congregations. These Separate or Strict Congregationalists were often poor. They rejected the necessity of an educated ministry, ministerial associations (which had tried to control the revival), and the Half-Way Covenant. Prone to schisms and forced to pay taxes for the state churches, Separate Congregatonalists did not survive long.[46] The more traditional ones returned to the established Congregational churches, while the most radical embraced adult baptism and became Baptists. Shubal Stearns, a Separate Congregationalist missionary to the South, became the founding father of the Separate Baptists.[47]

Beliefs

17th century

In the 17th century, Congregationalists were Puritans who still identified themselves as members of the Church of England.[6] As Calvinistic Protestants, Congregational churches shared common beliefs with other Reformed churches, such as sola scriptura,[48] unconditional election,[49] covenant theology,[50] Reformed worship, Reformed baptismal theology, and Reformed views on the Lord's Supper.[need citation] The Savoy Declaration, a modification of the Westminster Confession of Faith, was adopted as a Congregationalist confessional statement in Massachusetts in 1680 and in Connecticut in 1708.[51]

Congregational churches differed from Reformed churches in Europe by their belief that churches should be comprised of "visible saints", the elect. To ensure that only regenerated persons were admitted as full members, Congregational churches required prospective members to provide a conversion narrative describing their personal conversion experience.[52]

The process of conversion was described in different ways, but most ministers agreed that there were 3 essential stages. The first stage was humiliation or sorrow for having sinned against God. The second stage was justification or adoption characterized by a sense of having been forgiven and accepted by God through Christ's mercy. The third stage was sanctification, the ability to live a holy life out of gladness toward God.[53]

All settlers, whether full members or not, were required to attend church services and were subject to church discipline.[54] The Lord's Supper, however, was reserved to full members only.[52] While Congregational churches practiced infant baptism, only full members could present their children for baptism. It was believed that the children of church members already shared in their parent's covenant relationship with the church, and they therefore had a right to baptism by virtue of being born into a Christian household.[55]

References

Citations

- ^ Bremer 2009, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Bremer 2009, pp. 9, 20.

- ^ a b Cooper 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 17,19: "Likewise, though it had been practiced in New England for several years, they reaffirmed from First Corinthians that 'churches should be churches of saints' and must therefore require of members a test of grace, or conversion."

- ^ a b Bremer 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 24, 26.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 114, 221.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 31.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 14, 33.

- ^ Bremer 2009, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 116.

- ^ Youngs 1998, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 57.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 79–84.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 165–168.

- ^ Youngs 1998, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 60.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 62.

- ^ Youngs 1998, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 67.

- ^ a b Youngs 1998, p. 72.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 199.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 200.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 202–204.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Youngs 1998, p. 83.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 251.

- ^ a b Youngs 1998, p. 73.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 252.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Youngs 1998, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 259.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b Youngs 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Taves 1999, p. 71.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 215.

- ^ Campbell 2013.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 52.

- ^ a b Youngs 1998, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 50.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 170.

Bibliography

- Bremer, Francis J. (2009). Puritanism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199740871.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Donna M. (2013). "Puritanism in New England". wsu.edu. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, James F., Jr. (1999). Tenacious of Their Liberties: The Congregationalists in Colonial Massachusetts. Religion in America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195152875.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jefferson, Charles Edward (1910). Congregationalism. Boston: The Pilgrim Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taves, Ann (1999). Fits, Trances, and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from Wesley to James. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691010243.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walker, Williston (1894). A History of the Congregational Churches in the United States. American Church History. Vol. 3. New York: The Christian Literature Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Youngs, J. William T. (1998). The Congregationalists. Denominations in America. Vol. 4 (Student ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 9780275964412.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Church-Government and Church-Covenant Discussed by Richard Mather.

- A Survey of the Summe of Church-Discipline by Thomas Hooker.

- Walker, Williston (1893). The Creeds and Platforms of Congregationalism. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)