Cursive

Cursive (from Latin curro, currere, cucurri, cursum, to run, hasten[1]) is any style of handwriting that is designed for writing notes and letters quickly by hand. In the Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic writing systems, the letters in a word are connected, making a word one single complex stroke.

In the United States of America, the name "cursive" is most commonly used to describe this style of writing. In the United Kingdom and in Ireland, the phrase "joined-up writing", "real writing" or "joint writing" is far more commonly used, while the term "running writing" or just "cursive" is most commonly used in Australia. Cursive is also commonly known as simply "handwriting" in Canada, New Zealand, and the US. Cursive is considered distinct from the "printing" or "block letter" style of writing, in which the letters of a word are unconnected. A distinction is sometimes made between cursive hand(writing), such as the D'Nealian style, in which the risers of the letters are slanted loops, and letters such as f, r, s, z, D, F, G, L, Q are quite distinct in shape from their printed counterparts, and italic hand(writing), such as the Getty-Dubay style, also called print-writing, in which the risers are slanted straight lines and the letters are essentially printed letters joined together.

In Roman cursive, the letters are not connected. In the research domain of handwriting recognition, this writing style is called "connected italic", to indicate the difference between the phenomenon of italic script and sloppy appearance of individual letters ("cursive") and the phenomenon of connecting strokes between letters, i.e., a letter-to-letter transition without a pen lift ("connected cursive").

The origin of the cursive style is associated with practical advantages (writing speed, sparse pen lifting avoids ink smudges with the quill) and the individuality of the provenance of a document, as opposed to machine font.[2]

Cursive Greek

The Greek alphabet has had several cursive forms in the course of its development. In antiquity, a cursive form of handwriting was used in writing on papyrus. It employed slanted and partly connected letter forms as well as many ligatures. Some features of this handwriting were later adopted into Greek minuscule, the dominant form of handwriting in the medieval and early modern era. In the 19th and 20th centuries, an entirely new form of cursive Greek, more similar to contemporary Western European cursive scripts, was developed.

English Cursive

The English used joined-up writing before the Norman conquest. Anglo-Saxon Charters typically include a boundary clause written in Old English in a cursive script. A cursive handwriting style—secretary hand—was widely used for both personal correspondence and official documents in England from early in the 16th century.

Cursive handwriting developed into something approximating its current form from the 17th century, but its use was neither uniform, nor standardised either in England itself or elsewhere in the British Empire. In the English colonies of the early 17th century, most of the letters are clearly separated in the handwriting of William Bradford, though a few were joined as in a cursive hand. In England itself, Edward Crocker had begun to introduce a version of the French ronde style, which was then further developed and popularised throughout the British Empire in the 17th and 18th centuries as round hand by John Ayers and William Banson.[4]

Back in the American colonies, on the eve of their independance from the Kingdom of Great Britain, it is notable that Thomas Jefferson joined most, but not all of the letters when drafting the United States Declaration of Independence. However, a few days later, Timothy Matlack professionally re-wrote the presentation copy of the Declaration in a fully cursive hand. Eighty-seven years later, in the middle of the 19th century, Abraham Lincoln drafted the Gettysburg Address in a cursive hand that would not look out of place today.

In both the British Empire and the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, before the typewriter, professionals used cursive for their correspondence. This was called a "fair hand", meaning it looked good, and firms trained their clerks to write in exactly the same script.

In the mid-19th century, most children were taught cursive; in the United States, this usually occurred in second or third grade (around ages seven to nine). Few simplifications appeared as the middle of the 20th century approached.

After the 1960s, there lay an argument that cursive instruction was more difficult than it needed to be. There was the consideration that traditional cursive was unnecessary, and it was easier to write forms of simply slanted characters called italic. Because of this, a number of various new forms of cursive appeared in the late 20th century, including D'Nealian and Getty-Dubay; these models lacked the craftsmanship of earlier styles such as Spencerian Script, Zaner-Bloser, and the Palmer Method, but were less demanding. With the range of options available, handwriting became non-standardized across different school systems in different English-speaking countries.

With the advent of typewriters and computers, cursive as a way of formalizing correspondence has fallen out of favor. Most tasks which would have once required a "fair hand" are now done using word processing and a printer. However, some western etiquette advocates the use of longhand in personal notes (e.g., thank-you notes) to provide a sense that a real person is involved in the correspondence.

English cursive in education

In one academic study, first graders who could write only 10 to 12 letters per minute were given 45 minutes of handwriting instruction for nine weeks; their writing speed doubled, their expressed thoughts became more complex, and their sentence construction skills increased.[5]

On the 2006 SAT, a United States college entrance exam, only 15 percent of the students wrote their essay answers in cursive.[5]

In a 2007 survey of 200 teachers of first through third grades in all 50 American states, ninety percent of respondents said their schools required the teaching of cursive.[6]

In 2011, the American state of Indiana announced that its schools will no longer be required to teach cursive, and instead will teach "keyboard proficiency".[7]

Cursive Russian

The Russian cursive Cyrillic alphabet is used (instead of the block letters) when handwriting the modern Russian Language. Whilst some letters resemble their Latin counterparts, not all of them represent the same sound. Most handwritten Russian, especially personal letters and schoolwork, uses the cursive Russian (Cyrillic) alphabet. Most children in Russian schools are taught by 1st grade how to write using this Cyrillic script.

Cursive Chinese

Cursive forms of Chinese characters are used in calligraphy; "running script" is the semi-cursive form and "grass script" is the cursive. The running aspect of this script has more to do with the formation and connectedness of strokes within an individual character than with connections between characters as in Western connected cursive. The latter are rare in Hanzi and the derived Japanese Kanji characters which are usually well separated by the writer.

-

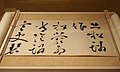

Semi-cursive style Calligraphy of Chinese poem by Mo Ruzheng

-

classical poem in cursive script at Treasures of Ancient China exhibit

-

8 cursive characters for dragon

-

Calligraphy of both cursive and semi-cursive by Dong Qichang

-

Four columns in cursive script quatrain poem, Quatrain on Heavenly Mountain. Attributed to Emperor Gaozong of Song, the tenth Chinese Emperor of the Song Dynasty

-

Chinese poem in cursive

-

One page of the album "Thousand Character classic in formal and Cursive script" attributed to Zhi Yong

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Cassell's Latin Dictionary, revised by Marchant & Charles, 260th Thousand

- ^ Georges Jean (1997). Writing: The story of alphabets and scripts, London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. [New Horizons]

- ^ Cardenio, Or, the Second Maiden's Tragedy, pp. 131-3: By William Shakespeare, Charles Hamilton, John Fletcher (Glenbridge Publishing Ltd., 1994) ISBN 0944435246

- ^ Whalley, Joyce Irene (1980). The Art of Calligraphy, Western Europe & America. London: Bloomsbury. p. 400. ISBN 0906223644.

- ^ a b "The Handwriting Is on the Wall", Washington Post, 11 October 2006. [1]

- ^ "Schools debate: Is cursive writing worth teaching?", USA Today, 23 January 2009. [2]

- ^ "Typing Beats Scribbling: Indiana Schools Can Stop Teaching Cursive", Time, 6 July 2011 [3]

External links

- Lessons in Calligraphy and Penmanship, including scans of classic nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century manuals and examples

- The Golden Age of American Penmanship, including scans of the January 1932 issue of Austin Norman Palmer's American Penman

- Normal and Bold Victorian Modern Cursive electronic fonts for downloading

- Mourning the Death of Handwriting, a TIME Magazine article on the demise of cursive handwriting

- Op-Art: The Write Stuff, a New York Times article on the advantages of Italic hand over both full cursive and block printing

- The Society for Italic Handwriting, supporters of teaching a simplified semi-cursive hand