Killing of Muhammad al-Durrah: Difference between revisions

replace hearsay with the pathologist. |

rv to SV - these changes are hopeless and riddled with POV-pushing |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

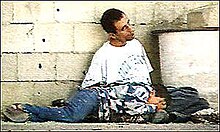

[[Image:AlDurrah1.jpg|thumb|230px|Muhammad al-Durrah and his father, Jamal, on September 30, 2000. The scene, now iconic, was recorded by Talal Abu Rahma for [[France 2]]. The boy was reported to have been killed, and his father injured.]] |

[[Image:AlDurrah1.jpg|thumb|230px|Muhammad al-Durrah and his father, Jamal, on September 30, 2000. The scene, now iconic, was recorded by Talal Abu Rahma for [[France 2]]. The boy was reported to have been killed, and his father injured.]] |

||

'''Muhammad Jamal al-Durrah''' (1988–September 30, 2000) {{lang-ar|محمد جمال الدرة}}) was a [[Palestinian people|Palestinian]] boy reported to have been killed by [[Israel Defense Forces]] (IDF) gunfire during a clash between the IDF and [[Palestinian Security Forces]] in the [[Gaza Strip]] on September 30, 2000, in the early days of the [[Second Intifada]].<ref name=Goldenberg>Goldenberg, Suzanne. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/israel/Story/0,2763,376639,00.html "Making of a martyr"], ''The Guardian'', October 3, 2000.</ref> The boy became a symbol of the |

'''Muhammad Jamal al-Durrah''' (1988–September 30, 2000) {{lang-ar|محمد جمال الدرة}}) was a [[Palestinian people|Palestinian]] boy reported to have been killed by [[Israel Defense Forces]] (IDF) gunfire during a clash between the IDF and [[Palestinian Security Forces]] in the [[Gaza Strip]] on September 30, 2000, in the early days of the [[Second Intifada]].<ref name=Goldenberg>Goldenberg, Suzanne. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/israel/Story/0,2763,376639,00.html "Making of a martyr"], ''The Guardian'', October 3, 2000.</ref> The boy became a symbol of the [[Israeli-Palestinian conflict]], and an icon and martyr throughout the Arab world.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/middle_east/952600.stm "Boy becomes Palestinian martyr"], BBC News, October 2, 2000; [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/975426.stm Children become symbol of struggle], BBC News, November 19, 2000.</ref> |

||

The [[Palestinian Authority]] had declared the day a general strike. Protesters had gathered to throw stones at an IDF outpost at the [[Netzarim junction]], and cameramen from several news agencies were filming them. Jamal al-Durrah and his son had arrived at the junction on their way back from a car auction and got caught up in the events.<ref name=Orme/> The violence escalated and shots were fired from the Israeli and Palestinian positions. Talal Abu Rahma, a freelance Palestinian cameraman working for France 2, was the only one to film the al-Durrahs.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/correspondent/1026340.stm "When Peace Died"], BBC News, November 17, 2000.</ref> His footage shows Muhammad and Jamal seeking cover behind a concrete cylinder—after a burst of gunfire, the boy slumps forward and his father appears injured.<ref>Schattner, Marius. "Pictures of death of Palestinian child plunge Israel into embarrassment," Agence France Presse, October 1, 2000; [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUhM2NZavcc 18 minutes of the |

The [[Palestinian Authority]] had declared the day a general strike. Protesters had gathered to throw stones at an IDF outpost at the [[Netzarim junction]], and cameramen from several news agencies were filming them. Jamal al-Durrah and his son had arrived at the junction on their way back from a car auction and got caught up in the events.<ref name=Orme/> The violence escalated and shots were fired from the Israeli and Palestinian positions. Talal Abu Rahma, a freelance Palestinian cameraman working for France 2, was the only one to film what happened to the al-Durrahs, though not who fired the shots.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/correspondent/1026340.stm "When Peace Died"], BBC News, November 17, 2000.</ref> His footage shows Muhammad and Jamal seeking cover behind a concrete cylinder—after a burst of gunfire, the boy slumps forward and his father appears injured.<ref>Schattner, Marius. "Pictures of death of Palestinian child plunge Israel into embarrassment," Agence France Presse, October 1, 2000; [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUhM2NZavcc 18 minutes of the France 2 raw footage]; the al-Durrah incident begins at 01:17:06:09, ''YouTube'', accessed September 18, 2009.</ref> A voice-over from [[Charles Enderlin]], the network's bureau chief in Israel, who was not present during the incident, said the boy and his father had been the "target of fire coming from the Israeli position."<ref name="Rosenthal">Rosenthal, John. [http://www.spme.net/cgi-bin/articles.cgi?ID=1358 France: The Al-Dura Defamation Case and the End of Free Speech], World Politics Watch, November 3, 2006.</ref> The boy's death was announced just after the shooting, and he was buried shortly thereafter.<ref>Jadallah, Ahmed. "Boy dies in father's arms in Gaza clashes," Reuters, September 30, 2000.</ref><ref name=Orme/> |

||

Israel accepted responsibility and apologized, but later investigations by the Israeli army and an independent French ballistics expert, and German television documentaries by [[Esther Shapira]], suggested either that the al-Durrahs |

Israel accepted responsibility and apologized, but later investigations by the Israeli army and an independent French ballistics expert, and two German television documentaries by [[Esther Shapira]], suggested either that the al-Durrahs may have been hit by Palestinian bullets, or that it remains unclear whether the boy died.<ref> |

||

*[http://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/28/world/28MIDE.html?ex=1212292800&en=8b0627a9965c4c3f&ei=5070 "Israeli Army Says Palestinians May Have Shot Gaza Boy"], ''The New York Times'', November 27, 2000. |

*[http://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/28/world/28MIDE.html?ex=1212292800&en=8b0627a9965c4c3f&ei=5070 "Israeli Army Says Palestinians May Have Shot Gaza Boy"], ''The New York Times'', November 27, 2000. |

||

*Patience, Martin. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7083129.stm Dispute rages over al-Durrah footage], BBC News, 8 November 2007. |

*Patience, Martin. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7083129.stm Dispute rages over al-Durrah footage], BBC News, 8 November 2007. |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

===Sharon's visit to Temple Mount=== |

===Sharon's visit to Temple Mount=== |

||

[[File:Ariel Sharon Headshot.jpg|left|thumb|130px|Rioting followed the visit of [[Ariel Sharon]], then opposition leader, to the [[Temple Mount]] in Jerusalem.]] |

[[File:Ariel Sharon Headshot.jpg|left|thumb|130px|Rioting followed the visit of [[Ariel Sharon]], then opposition leader, to the [[Temple Mount]] in Jerusalem.]] |

||

On September 28, 2000, two days prior to the incident, the Israeli opposition leader [[Ariel Sharon]] visited the [[Temple Mount]] in the [[Old City of Jerusalem]].<ref name="nytimes_outbreak">{{cite news|title= Palestinians And Israelis In a Clash At Holy Site|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9502E4DA1E3AF93BA1575AC0A9669C8B63|publisher=[[New York Times]]|date=[[September 28]], [[2000]]}}</ref> His [[Second Intifada#Sharon visits the Temple Mount|controversial visit]] was condemned by the Palestinians as a provocation and the following day, September 29, violence broke out in and around the Old City resulting in seven Palestinians being killed by Israeli security forces and 300 more being wounded.<ref>Menachem Klein,''The Jerusalem Problem: The Struggle for Permanent Status'', University Press of Florida, 2003 p.97</ref> On September 30, protests against the previous day's deaths escalated into widespread violence across the West Bank and Gaza Strip in which fifteen Palestinians were reported killed, five of them in the Gaza Strip. The clashes included a gun battle between Palestinian police and Israeli soldiers in the Gaza Strip.<ref name="bbc-violence-engulfs">"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/949760.stm Violence engulfs West Bank and Gaza]", BBC News, September 30, 2000.</ref> It was in the course of this battle, in which Palestinian security forces sided with rioting Palestinian civilians against Israeli soldiers, that al-Durrah and his father were filmed as they sought shelter from the hail of gunfire.<ref name="bbc-drowning">"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/950760.stm Mid-East peace 'drowning in blood']", BBC News, [[October 1]] [[2000]].</ref> Three Palestinians were reported killed by gunfire near the Israeli settlement of Netzarim on that day. The Israeli army and Palestinian security forces in the Gaza Strip agreed to a ceasefire in the aftermath of the violence.<ref name="bbc-clashes">"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/951046.stm Fierce clashes in Gaza and West Bank]", BBC News, October 2, 2000.</ref> |

On September 28, 2000, two days prior to the incident, the Israeli opposition leader [[Ariel Sharon]] visited the [[Temple Mount]] in the [[Old City of Jerusalem]].<ref name="nytimes_outbreak">{{cite news|title= Palestinians And Israelis In a Clash At Holy Site|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9502E4DA1E3AF93BA1575AC0A9669C8B63|publisher=[[New York Times]]|date=[[September 28]], [[2000]]}}</ref> His [[Second Intifada#Sharon visits the Temple Mount|controversial visit]] was condemned by the Palestinians as a provocation and the following day, September 29, violence broke out in and around the Old City resulting in seven Palestinians being killed by Israeli security forces and 300 more being wounded.<ref>Menachem Klein,''The Jerusalem Problem: The Struggle for Permanent Status'', University Press of Florida, 2003 p.97</ref> On September 30, protests against the previous day's deaths escalated into widespread violence across the West Bank and Gaza Strip in which fifteen Palestinians were reported killed, five of them in the Gaza Strip. The clashes included a gun battle between Palestinian police and Israeli soldiers in the Gaza Strip.<ref name="bbc-violence-engulfs">"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/949760.stm Violence engulfs West Bank and Gaza]", BBC News, September 30, 2000.</ref> It was in the course of this battle, in which Palestinian security forces sided with rioting Palestinian civilians against Israeli soldiers, that al-Durrah and his father were filmed as they sought shelter from the hail of gunfire.<ref name="bbc-drowning">"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/950760.stm Mid-East peace 'drowning in blood']", BBC News, [[October 1]] [[2000]].</ref> Three Palestinians were reported killed by gunfire near the Israeli settlement of Netzarim on that day. The Israeli army and Palestinian security forces in the Gaza Strip agreed to a ceasefire in the aftermath of the violence.<ref name="bbc-clashes">"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/951046.stm Fierce clashes in Gaza and West Bank]", BBC News, October 2, 2000.</ref> |

||

===Netzarim junction=== |

===Netzarim junction=== |

||

[[Image:Netzarim junction map.png|right|thumb|200px|Map of the Gaza Strip illustrating the locations of [[Bureij (camp)|Bureij]] refugee camp, the [[Netzarim]] settlement and the Netzarim Junction]] |

[[Image:Netzarim junction map.png|right|thumb|200px|Map of the Gaza Strip illustrating the locations of [[Bureij (camp)|Bureij]] refugee camp, the [[Netzarim]] settlement and the Netzarim Junction]] |

||

The incident occurred at the Netzarim junction, a crossroads which is situated a few kilometers south of [[Gaza City]] (at {{coord|31.465129|N|34.426689|E|type:landmark}}) on Saladin Road, the main route through the Gaza Strip. A short distance to the west lay the [[Israeli settlement]] of [[Netzarim]], which was |

The incident occurred at the Netzarim or al-Shohada junction, a crossroads which is situated a few kilometers south of [[Gaza City]] (at {{coord|31.465129|N|34.426689|E|type:landmark}}) on Saladin Road, the main route through the Gaza Strip. A short distance to the west lay the [[Israeli settlement]] of [[Netzarim]], which was dismantled in 2005 when Israel [[Israel's unilateral disengagement plan|withdrew from the Gaza Strip]]. The junction was the site of a "heavily fortified" Israeli military outpost codenamed Magen-3 which guarded the approach to the settlement.<ref name="osullivan">O'Sullivan, Arieh. "Southern Command decorates soldiers, units". ''Jerusalem Post'', [[June 6]] [[2001]]</ref><ref name="Philps">Philps, Alan. "[http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/palestinianauthority/1368574/Death-of-boy-caught-in-gun-battle-provokes-wave-of-revenge-attacks.html Death of boy caught in gun battle provokes wave of revenge attacks]". ''Daily Telegraph'', [[October 1]] [[2000]]</ref> On the day of the shooting itself, the outpost was manned by eighteen Israeli soldiers<ref name="gross">Gross, Netty C. "Split Screen". ''[[The Jerusalem Report]]'', [[April 21]] [[2003]].</ref> from the [[Givati Brigade]] Engineering Platoon and the [[Herev Battalion]].<ref name="osullivan" /> A small post manned by Palestinian policemen stood on the diagonally opposite side of the junction.<ref name=Goldenberg /> |

||

The presence of Israelis at Netzarim was vehemently opposed by local Palestinians, such that the inhabitants of the settlement were under strict orders to travel only with a military escort. It was the scene of "constant flashpoints with assailants attacking the [escort] vehicles with firebombs and rocks."<ref name="CNN-9-27-200">[http://archives.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/meast/09/27/israel.attack.ap/index.html CNN '' Israeli settler convoy bombed in Gaza, three injured'' September 27, 2000]</ref> Palestinian and Israeli security forces had previously mounted joint patrols in the area under [[Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip|interim peace arrangements]],<ref name=Goldenberg/> but in the days leading up to the shooting, there had been a series of violent incidents in the vicinity of Netzarim.<ref name="CNN-9-27-200" /> Israel's ambassador explained in a letter to the United Nations that, "The attacks began with the throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails in the vicinity of the Netzarim Junction on 13 September. This was followed by the killing of an Israeli soldier by a roadside bomb on 27 September, and the murder of an Israeli police officer by a Palestinian policeman in a joint patrol on 29 September."<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20010319023047/http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/f45643a78fcba719852560f6005987ad/f6b91be9ecd0b9be8525696f004c1330!OpenDocument Letter dated 2 October 2000 from the Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General], October 2, 2000, accessed October 13, 2009.</ref> |

The presence of Israelis at Netzarim was vehemently opposed by local Palestinians, such that the inhabitants of the settlement were under strict orders to travel only with a military escort. It was the scene of "constant flashpoints with assailants attacking the [escort] vehicles with firebombs and rocks."<ref name="CNN-9-27-200">[http://archives.cnn.com/2000/WORLD/meast/09/27/israel.attack.ap/index.html CNN '' Israeli settler convoy bombed in Gaza, three injured'' September 27, 2000]</ref> Palestinian and Israeli security forces had previously mounted joint patrols in the area under [[Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip|interim peace arrangements]],<ref name=Goldenberg/> but in the days leading up to the shooting, there had been a series of violent incidents in the vicinity of Netzarim.<ref name="CNN-9-27-200" /> Israel's ambassador explained in a letter to the United Nations that, "The attacks began with the throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails in the vicinity of the Netzarim Junction on 13 September. This was followed by the killing of an Israeli soldier by a roadside bomb on 27 September, and the murder of an Israeli police officer by a Palestinian policeman in a joint patrol on 29 September."<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20010319023047/http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/f45643a78fcba719852560f6005987ad/f6b91be9ecd0b9be8525696f004c1330!OpenDocument Letter dated 2 October 2000 from the Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General], October 2, 2000, accessed October 13, 2009.</ref> |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

According to Amal al-Durrah, the boy's mother, on the evening before the shooting Muhammad had been watching the violence in Jerusalem on television and asked "Can I go to join the protests in Netzarim [on Saturday]?" He had been known in the past to run off to the beach or to watch older boys throwing stones during protests. {{fact}} In an interview in the Shifa hospital the day after the shooting, Jamal told Talal Abu Rahma, the cameraman who filmed the shooting, that he and Muhammad had gone out looking at secondhand cars. Having failed to buy anything, they decided to take a cab home, which was two kilometers away.<ref name=AbuRahmaaffidavit2>Abu Rahma, Talal. [http://www.pchrgaza.ps/special/tv2.htm "Statement under oath by a photographer of France 2 Television"], Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, October 3, 2000. Abu Rahma said in an affidavit sworn in October 2000 that he was the first journalist to interview the father after the incident. The interview was taped and broadcast.</ref> |

According to Amal al-Durrah, the boy's mother, on the evening before the shooting Muhammad had been watching the violence in Jerusalem on television and asked "Can I go to join the protests in Netzarim [on Saturday]?" He had been known in the past to run off to the beach or to watch older boys throwing stones during protests. {{fact}} In an interview in the Shifa hospital the day after the shooting, Jamal told Talal Abu Rahma, the cameraman who filmed the shooting, that he and Muhammad had gone out looking at secondhand cars. Having failed to buy anything, they decided to take a cab home, which was two kilometers away.<ref name=AbuRahmaaffidavit2>Abu Rahma, Talal. [http://www.pchrgaza.ps/special/tv2.htm "Statement under oath by a photographer of France 2 Television"], Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, October 3, 2000. Abu Rahma said in an affidavit sworn in October 2000 that he was the first journalist to interview the father after the incident. The interview was taped and broadcast.</ref> |

||

At around lunchtime, they arrived near the Netzarim junction where Palestinians were throwing stones and [[Molotov cocktail]]s at Israeli soldiers protecting a nearby [[Israeli settlement]].<ref name=Rees>Rees, Matt. [http://www.time.com/time/pacific/magazine/20001225/poy_mohammed.html "Mohammed al-Dura"], ''Time'', [[December 25]] [[2000]].</ref> With the cab driver unwilling to go further because of the rioting,<ref name=Orme/> Jamal decided to cross the junction on foot to look for another cab. |

At around lunchtime, they arrived near the Netzarim junction where Palestinians were throwing stones and [[Molotov cocktail]]s at Israeli soldiers protecting a nearby [[Israeli settlement]].<ref name=Rees>Rees, Matt. [http://www.time.com/time/pacific/magazine/20001225/poy_mohammed.html "Mohammed al-Dura"], ''Time'', [[December 25]] [[2000]].</ref> With the cab driver unwilling to go further because of the rioting,<ref name=Orme/> Jamal decided to cross the junction on foot to look for another cab.<ref name=AbuRahmaaffidavit>Abu Rahma, Talal. [http://www.pchrgaza.ps/special/tv2.htm "Statement under oath by a photographer of France 2 Television"], Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, October 3, 2000.</ref> |

||

According to Matt Rees of ''Time'', Palestinian gunmen started shooting at the Israeli soldiers from a nearby orange grove.<ref name=Rees/> Israeli troops returned fire with rubber-coated bullets and live rounds which the army said its soldiers fired in the direction of the nearby Palestinian police post.<ref>Laub, Karen. "Twelve killed in Israeli-Palestinian clashes; worst violence in four years." Associated Press, September 30, 2000.</ref> Muhammad and his father crouched behind a concrete drum situated diagonally opposite the Israeli outpost.<ref name=Rees/> |

According to Matt Rees of ''Time'', Palestinian gunmen started shooting at the Israeli soldiers from a nearby orange grove.<ref name=Rees/> Israeli troops returned fire with rubber-coated bullets and live rounds which the army said its soldiers fired in the direction of the nearby Palestinian police post.<ref>Laub, Karen. "Twelve killed in Israeli-Palestinian clashes; worst violence in four years." Associated Press, September 30, 2000.</ref> Muhammad and his father crouched behind a concrete drum situated diagonally opposite the Israeli outpost.<ref name=Rees/> |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

The tape was edited for broadcast by [[Charles Enderlin]], a French-Israeli journalist who was France 2's bureau chief in Israel at the time. The original tape was edited down to 59 seconds, with a voiceover provided by Enderlin. Enderlin was not present during the shooting itself. |

The tape was edited for broadcast by [[Charles Enderlin]], a French-Israeli journalist who was France 2's bureau chief in Israel at the time. The original tape was edited down to 59 seconds, with a voiceover provided by Enderlin. Enderlin was not present during the shooting itself. |

||

The tape as broadcast shows Muhammad and his father crouching behind the cylinder, situated between the Israeli and Palestinian positions, the child screaming and the father shielding him.<ref name=Rees/> The father is shown waving toward the Israeli position, shouting |

The tape as broadcast shows Muhammad and his father crouching behind the cylinder, situated between the Israeli and Palestinian positions, the child screaming and the father shielding him. Matt Rees writes that Muhammed told his father "Don't worry, Daddy, the ambulance will come and rescue us."<ref name=Rees/> The father is shown waving toward the Israeli position, shouting "Don't shoot!" The camera goes out of focus at the moment of the reported shooting. A final frame shows the father sitting upright, appearing to have been injured, and the boy lying over his legs.<ref name=France2minutes>These are the extra minutes according to Richard Landes on ''Seconddraft.org'', [http://www.seconddraft.org/new_aldurah/france2raw.wmv] (Windows Media Player) and the BBC [http://news.bbc.co.uk/olmedia/950000/video/_952600_shooting2_vi.ram] (Real Video format). Landes says France 2 gave these few minutes of footage to the other news media in the area and to the Israeli military.</ref> In his voiceover, Enderlin stated that the IDF had killed the boy.<ref name=EnderlinFigaro>Enderlin, Charles. [http://www.shalomarchav.be/imprimer.php3?id_article=978 "Non à la censure à la source"], ("No to censorship at the source") ''Le Figaro'', January 27, 2005.</ref> |

||

===Deaths reported=== |

===Deaths reported=== |

||

Reuters cameraman Ahmad Jadallah said that ambulances were called to the scene but were delayed by the intensity of the shooting, with the wounded and dying lying in the road for a long time.<ref name=Jadallah>Jadallah, Ahmed. "Boy dies in father's arms in Gaza clashes". Reuters, September 30 2000.</ref> According to Abu Rahma, "It took about 45 minutes for the ambulance to reach the two, because of the heavy Israeli firing on everyone who dared to reach the young boy and his father."<ref> "An image that will haunt the world". ''[[The Star (Amman newspaper)|The Star (Amman)]]'', October 5, 2000.</ref> |

Reuters cameraman Ahmad Jadallah<ref name="Dignity"> [http://www.humiliationstudies.org/news/archives/2005_10.html Human Dignity and Humiliation Studies] September, 2005 </ref> said that ambulances were called to the scene but were delayed by the intensity of the shooting, with the wounded and dying lying in the road for a long time.<ref name=Jadallah>Jadallah, Ahmed. "Boy dies in father's arms in Gaza clashes". Reuters, September 30 2000.</ref> According to Abu Rahma, "It took about 45 minutes for the ambulance to reach the two, because of the heavy Israeli firing on everyone who dared to reach the young boy and his father."<ref> "An image that will haunt the world". ''[[The Star (Amman newspaper)|The Star (Amman)]]'', October 5, 2000.</ref> Bassam al-Bilbeisi, the driver of the first ambulance, was shot dead as the fighting continued.<ref name=Orme/> |

||

An ambulance took the boy and his father to the nearby Shifa hospital in Gaza, where Muhammad was pronounced dead on arrival.<ref name="Leigh">Leigh, David. "Don't worry Dad: My boy's last words before he died in a hail of army bullets". ''Daily Mirror'', January 11, 2001.</ref> The deaths of al-Durrah, the ambulance driver, and a Palestinian policeman were confirmed a few hours later by the Shifa hospital.<ref>[http://www.commondreams.org/headlines/100200-01.htm "Muhammad al-Durrah: A Young Symbol of Mideast Violence"], ''The New York Times, October 2, 2000. Reprinted at CommonDreams.</ref> |

An ambulance took the boy and his father to the nearby Shifa hospital in Gaza, where Muhammad was pronounced dead on arrival.<ref name="Leigh">Leigh, David. "Don't worry Dad: My boy's last words before he died in a hail of army bullets". ''Daily Mirror'', January 11, 2001.</ref> His death was reported by an Associated Press correspondent, Karin Laub, at 12:35 pm local time.<ref>{{cite news|last=Laub|first=Karin|title=Twelve killed in Israeli-Palestinian clashes; worst violence in four years|agency=Associated Press}}</ref> The deaths of al-Durrah, the ambulance driver, and a Palestinian policeman were confirmed a few hours later by the Shifa hospital.<ref>[http://www.commondreams.org/headlines/100200-01.htm "Muhammad al-Durrah: A Young Symbol of Mideast Violence"], ''The New York Times, October 2, 2000. Reprinted at CommonDreams.</ref> A further thirty people, including six Palestinian policemen, were reported to have been injured in the gun battle.<ref>"Shootout between Israeli army, Palestinian police: witnesses". Agence France-Presse, September 30, 2000.</ref> |

||

===Injuries=== |

===Injuries=== |

||

Muhammad was reported by the BBC to have been shot four times. |

Muhammad was reported by the BBC to have been shot four times.Talal Abu Rahma referred in his affidavit to one shot to the boy's right leg, while ''TIME'' said he had received a fatal wound to the abdomen.<ref name=BBCOctober2>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/middle_east/952600.stm "Boy becomes Palestinian martyr"], BBC News, October 2, 2000.</ref><ref name=AbuRahmaaffidavit/><ref name=Rees/> No autopsy was performed.<ref name=Lappen>Lappen, Alyssa A. [http://www.frontpagemag.com/Articles/ReadArticle.asp?ID=16432 "The Israeli crime that wasn't"], ''FrontPage magazine'', December 28, 2004.</ref> He was buried before sundown, in accordance with Muslim tradition, in an emotional public funeral at the Bureij camp in which his body was displayed wrapped in a [[Palestinian flag]].<ref name="Philps" /><ref name=Orme/> |

||

His father was evacuated on October 2 by the [[Royal Jordanian Air Force]] and taken to the Hussein Medical Centre in [[Amman]], Jordan,<ref name="Leigh" /><ref>"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/953235.stm Mideast violence intensifies]", BBC News, October 2, 2000</ref> where he was treated for wounds to both legs, one arm, and his midsection.<ref name="Tierney">Tierney, Michael. ''Glasgow Herald'', [[August 23]] [[2003]]</ref> He underwent a number of operations and was visited by [[Abdullah II of Jordan|King Abdullah of Jordan]],<ref name="mekki">Mekki, Hassan. "Israelis admit troops killed 12-year-old boy: 'My son was terrified'". Agence France-Presse, October 4, 2000.</ref> and the Libyan President, [[Muammar al-Gaddafi]]. He underwent four months of treatment in the hospital before returning to Gaza. He was reported to have been struck by twelve bullets,<ref name="Tierney" /> some of which were removed from his arm and pelvis.<ref name=BBCOctober3>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/954703.stm "Israel 'sorry' for killing boy"], BBC News, October 3, 2000.</ref> Jordanian doctors said his right hand would be permanently paralyzed, and that he had been traumatized.<ref name="mekki" /> His injuries were later questioned by an Israeli doctor; see [[#Questions raised about father's injuries|below]]. |

His father was evacuated on October 2 by the [[Royal Jordanian Air Force]] and taken to the Hussein Medical Centre in [[Amman]], Jordan,<ref name="Leigh" /><ref>"[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/953235.stm Mideast violence intensifies]", BBC News, October 2, 2000</ref> where he was treated for wounds to both legs, one arm, and his midsection.<ref name="Tierney">Tierney, Michael. ''Glasgow Herald'', [[August 23]] [[2003]]</ref> He underwent a number of operations and was visited by [[Abdullah II of Jordan|King Abdullah of Jordan]],<ref name="mekki">Mekki, Hassan. "Israelis admit troops killed 12-year-old boy: 'My son was terrified'". Agence France-Presse, October 4, 2000.</ref> and the Libyan President, [[Muammar al-Gaddafi]]. He underwent four months of treatment in the hospital before returning to Gaza. He was reported to have been struck by twelve bullets,<ref name="Tierney" /> some of which were removed from his arm and pelvis.<ref name=BBCOctober3>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/954703.stm "Israel 'sorry' for killing boy"], BBC News, October 3, 2000.</ref> Jordanian doctors said his right hand would be permanently paralyzed, and that he had been traumatized.<ref name="mekki" /> His injuries were later questioned by an Israeli doctor; see [[#Questions raised about father's injuries|below]]. |

||

Revision as of 11:33, 14 October 2009

Muhammad Jamal al-Durrah (1988–September 30, 2000) Arabic: محمد جمال الدرة) was a Palestinian boy reported to have been killed by Israel Defense Forces (IDF) gunfire during a clash between the IDF and Palestinian Security Forces in the Gaza Strip on September 30, 2000, in the early days of the Second Intifada.[1] The boy became a symbol of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and an icon and martyr throughout the Arab world.[2]

The Palestinian Authority had declared the day a general strike. Protesters had gathered to throw stones at an IDF outpost at the Netzarim junction, and cameramen from several news agencies were filming them. Jamal al-Durrah and his son had arrived at the junction on their way back from a car auction and got caught up in the events.[3] The violence escalated and shots were fired from the Israeli and Palestinian positions. Talal Abu Rahma, a freelance Palestinian cameraman working for France 2, was the only one to film what happened to the al-Durrahs, though not who fired the shots.[4] His footage shows Muhammad and Jamal seeking cover behind a concrete cylinder—after a burst of gunfire, the boy slumps forward and his father appears injured.[5] A voice-over from Charles Enderlin, the network's bureau chief in Israel, who was not present during the incident, said the boy and his father had been the "target of fire coming from the Israeli position."[6] The boy's death was announced just after the shooting, and he was buried shortly thereafter.[7][3]

Israel accepted responsibility and apologized, but later investigations by the Israeli army and an independent French ballistics expert, and two German television documentaries by Esther Shapira, suggested either that the al-Durrahs may have been hit by Palestinian bullets, or that it remains unclear whether the boy died.[8] France 2's news editor, Arlette Chabot, said in 2005 that no one could say for sure who fired the shots.[9] A French media commentator, Philippe Karsenty, was sued by France 2 for defamation, after he accused Enderlin of perpetrating a hoax; a verdict in 2006 in the network's favour was set aside by the Paris Court of Appeal in 2008.[10] France 2 has appealed to the Cour de cassation, France's highest court, a case that is ongoing.[11]

Background

Sharon's visit to Temple Mount

On September 28, 2000, two days prior to the incident, the Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon visited the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem.[12] His controversial visit was condemned by the Palestinians as a provocation and the following day, September 29, violence broke out in and around the Old City resulting in seven Palestinians being killed by Israeli security forces and 300 more being wounded.[13] On September 30, protests against the previous day's deaths escalated into widespread violence across the West Bank and Gaza Strip in which fifteen Palestinians were reported killed, five of them in the Gaza Strip. The clashes included a gun battle between Palestinian police and Israeli soldiers in the Gaza Strip.[14] It was in the course of this battle, in which Palestinian security forces sided with rioting Palestinian civilians against Israeli soldiers, that al-Durrah and his father were filmed as they sought shelter from the hail of gunfire.[15] Three Palestinians were reported killed by gunfire near the Israeli settlement of Netzarim on that day. The Israeli army and Palestinian security forces in the Gaza Strip agreed to a ceasefire in the aftermath of the violence.[16]

Netzarim junction

The incident occurred at the Netzarim or al-Shohada junction, a crossroads which is situated a few kilometers south of Gaza City (at 31°27′54″N 34°25′36″E / 31.465129°N 34.426689°E) on Saladin Road, the main route through the Gaza Strip. A short distance to the west lay the Israeli settlement of Netzarim, which was dismantled in 2005 when Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip. The junction was the site of a "heavily fortified" Israeli military outpost codenamed Magen-3 which guarded the approach to the settlement.[17][18] On the day of the shooting itself, the outpost was manned by eighteen Israeli soldiers[19] from the Givati Brigade Engineering Platoon and the Herev Battalion.[17] A small post manned by Palestinian policemen stood on the diagonally opposite side of the junction.[1]

The presence of Israelis at Netzarim was vehemently opposed by local Palestinians, such that the inhabitants of the settlement were under strict orders to travel only with a military escort. It was the scene of "constant flashpoints with assailants attacking the [escort] vehicles with firebombs and rocks."[20] Palestinian and Israeli security forces had previously mounted joint patrols in the area under interim peace arrangements,[1] but in the days leading up to the shooting, there had been a series of violent incidents in the vicinity of Netzarim.[20] Israel's ambassador explained in a letter to the United Nations that, "The attacks began with the throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails in the vicinity of the Netzarim Junction on 13 September. This was followed by the killing of an Israeli soldier by a roadside bomb on 27 September, and the murder of an Israeli police officer by a Palestinian policeman in a joint patrol on 29 September."[21]

Al-Durrah biographical details

Muhammad al-Durrah was in fifth grade in September 2000. He lived with his mother, Amal, his father, Jamal, and his four brothers and two sisters in the United Nations-run Bureij refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, several kilometers south of the Netzarim junction. His father was a carpenter and house painter who had worked for Israelis in north Tel Aviv for twenty years.[3][22] On the day of the incident, Muhammad's school was closed because of a Palestinian general strike, and his father was unable to go to work because Israel had closed its border with Gaza after the rioting in Jerusalem the previous day.[23]

The incident as initially reported

Arrival at Netzarim junction

|

|

|

According to Amal al-Durrah, the boy's mother, on the evening before the shooting Muhammad had been watching the violence in Jerusalem on television and asked "Can I go to join the protests in Netzarim [on Saturday]?" He had been known in the past to run off to the beach or to watch older boys throwing stones during protests. [citation needed] In an interview in the Shifa hospital the day after the shooting, Jamal told Talal Abu Rahma, the cameraman who filmed the shooting, that he and Muhammad had gone out looking at secondhand cars. Having failed to buy anything, they decided to take a cab home, which was two kilometers away.[29]

At around lunchtime, they arrived near the Netzarim junction where Palestinians were throwing stones and Molotov cocktails at Israeli soldiers protecting a nearby Israeli settlement.[30] With the cab driver unwilling to go further because of the rioting,[3] Jamal decided to cross the junction on foot to look for another cab.[31]

According to Matt Rees of Time, Palestinian gunmen started shooting at the Israeli soldiers from a nearby orange grove.[30] Israeli troops returned fire with rubber-coated bullets and live rounds which the army said its soldiers fired in the direction of the nearby Palestinian police post.[32] Muhammad and his father crouched behind a concrete drum situated diagonally opposite the Israeli outpost.[30]

The shooting

The violence at the junction was recorded by cameramen working for several news agencies.[33] The only cameraman to record the al-Durrah shooting was Talal Abu Rahma, a freelance Palestinian cameraman who lives in the Gaza Strip, and who was working alone in the area for France 2. Abu Rahma captured on tape 27 minutes of the reported 45-minute exchange of fire.[31]

The tape was edited for broadcast by Charles Enderlin, a French-Israeli journalist who was France 2's bureau chief in Israel at the time. The original tape was edited down to 59 seconds, with a voiceover provided by Enderlin. Enderlin was not present during the shooting itself.

The tape as broadcast shows Muhammad and his father crouching behind the cylinder, situated between the Israeli and Palestinian positions, the child screaming and the father shielding him. Matt Rees writes that Muhammed told his father "Don't worry, Daddy, the ambulance will come and rescue us."[30] The father is shown waving toward the Israeli position, shouting "Don't shoot!" The camera goes out of focus at the moment of the reported shooting. A final frame shows the father sitting upright, appearing to have been injured, and the boy lying over his legs.[28] In his voiceover, Enderlin stated that the IDF had killed the boy.[34]

Deaths reported

Reuters cameraman Ahmad Jadallah[35] said that ambulances were called to the scene but were delayed by the intensity of the shooting, with the wounded and dying lying in the road for a long time.[36] According to Abu Rahma, "It took about 45 minutes for the ambulance to reach the two, because of the heavy Israeli firing on everyone who dared to reach the young boy and his father."[37] Bassam al-Bilbeisi, the driver of the first ambulance, was shot dead as the fighting continued.[3]

An ambulance took the boy and his father to the nearby Shifa hospital in Gaza, where Muhammad was pronounced dead on arrival.[38] His death was reported by an Associated Press correspondent, Karin Laub, at 12:35 pm local time.[39] The deaths of al-Durrah, the ambulance driver, and a Palestinian policeman were confirmed a few hours later by the Shifa hospital.[40] A further thirty people, including six Palestinian policemen, were reported to have been injured in the gun battle.[41]

Injuries

Muhammad was reported by the BBC to have been shot four times.Talal Abu Rahma referred in his affidavit to one shot to the boy's right leg, while TIME said he had received a fatal wound to the abdomen.[42][31][30] No autopsy was performed.[43] He was buried before sundown, in accordance with Muslim tradition, in an emotional public funeral at the Bureij camp in which his body was displayed wrapped in a Palestinian flag.[18][3]

His father was evacuated on October 2 by the Royal Jordanian Air Force and taken to the Hussein Medical Centre in Amman, Jordan,[38][44] where he was treated for wounds to both legs, one arm, and his midsection.[45] He underwent a number of operations and was visited by King Abdullah of Jordan,[46] and the Libyan President, Muammar al-Gaddafi. He underwent four months of treatment in the hospital before returning to Gaza. He was reported to have been struck by twelve bullets,[45] some of which were removed from his arm and pelvis.[47] Jordanian doctors said his right hand would be permanently paralyzed, and that he had been traumatized.[46] His injuries were later questioned by an Israeli doctor; see below.

Cameraman's story

Charles Enderlin, the France 2 correspondent, later wrote in Le Figaro that he had based his initial allegation that the IDF had shot al-Durrah on the claim of the cameraman, Talal Abu Rahma.[34]

According to the Palestine Centre for Human Rights, Abu Rahma said in a sworn affidavit that he believed the IDF had shot the boy, and had done so intentionally.[31] France 2's communications director later said that Abu Rahma denied making this statement.[49] Suzanne Goldenberg, writing in The Guardian, also quoted Abu Rahma as saying of the IDF: "They were cleaning the area. Of course they saw the father, They were aiming at the boy, and that is what surprised me, yes, because they were shooting at him, not only one time, but many times".[1] In his affidavit, the cameraman said he had been alerted to the incident while at the northern part of the road leading to the Nezarim junction, also called the Al-Shohada’ junction. He said he could see an Israeli military outpost at the northwest of the junction, and just beind it, two Palestinian apartment blocks, nicknamed "the twins." He said he could also see a Palestinian National Security Forces outpost (police station), located south of the junction, just behind the spot where the father and boy were crouching. He said that shooting was coming from there too, but not, he said, during the time the boy was reportedly shot. The Israeli fire was being directed at this Palestinian outpost, he said. There was another Palestinian outpost 30 meters away.[31]

Abu Rahma said his attention was drawn to the child by Shams Oudeh, a Reuters photographer who was sitting beside Muhammad al-Durrah and his father. The three of them were sheltering behind a concrete block.[31] Regarding the shooting, Abu Rahma's affidavit said:

Shooting started first from different sources, Israeli and Palestinian. It lasted for not more than 5 minutes. Then, it was quite clear for me that shooting was towards the child Mohammed and his father from the opposite direction to them. Intensive and intermittent shooting was directed at the two and the two outposts of the Palestinian National Security Forces. The Palestinian outposts were not a source of shooting, as shooting from inside these outposts had stopped after the first five minutes, and the child and his father were not injured then. Injuring and killing took place during the following 45 minutes.

I can assert that shooting at the child Mohammed and his father Jamal came from the above-mentioned Israeli military outpost, as it was the only place from which shooting at the child and his father was possible. So, by logic and nature, my long experience in covering hot incidents and violent clashes, and my ability to distinguish sounds of shooting, I can confirm that the child was intentionally and in cold blood shot dead and his father injured by the Israeli army.[31]

The authenticity of this affidavit is unclear. It was apparently given to the Palestine Centre for Human Rights in Gaza on October 3, 2000, and signed by the cameraman in front of a lawyer, Raji Sourani. France 2's communications director, Christine Delavennat, later said that Abu Rahma "denied making a statement—falsely attributed to him by a human rights group [the Palestine Centre for Human Rights]—to the effect that the Israeli army fired at the boy in cold blood."[49]

There is a cut in Abu Rahma's footage of the father and son under attack which France 2 later attributed to efforts to preserve a low battery.[26] Abu Rahma also spoke of his fear for his own life and the possibility that he might be seen as a threat: "I was sitting on my knees and hiding my head, carrying my camera, and I was afraid from the Israelis to see this camera, maybe they will think this is a weapon, you know, or I am trying to shoot on them."[50] After about an hour, he said, during which time the al-Durrahs were evacuated by ambulance, Abu Rahma and the others with him managed to escape from the scene. The footage was sent to France 2's Jerusalem office where Charles Enderlin compiled his report and transmitted it by satellite to Paris.[51]

Abu Rahma has expressed his anger at being accused of using the incident to further the Palestinian cause. He told On the Media: "I think these people, they don't need me to defend them, you know. I'm professional journalist. I will never do it. I will never use journalism for anything ... because journalism is my religion. Journalism—it's my nationality. Even journalism is my language!"[52]

Israeli soldiers' story

The Israeli soldiers stationed at the Netzarim junction outpost were later interviewed by Israel Radio. Second Lieutenant Idan Quris, who was in command of an engineering platoon at the outpost, said: "We didn't know about the death of the kid for three days. Believe me, all of our efforts were aimed at armed Palestinians. We don't know how he was killed." The acting commander of the Netzarim position, Lieutenant-Colonel Nizar Fares, said: "The amount of fire that was directed at the position surprised even us. ... When the kid was killed, no one saw him from the position. It is difficult to command this kind of position which is under massive gunfire for such a long period of time and in the end succeed in the mission, return everyone safely and maintain the position."[17]

Reaction

Family

Muhammad's mother, Amal, watched the incident on television and worried that her husband and son had not returned home, but did not initially recognize the two figures she saw sheltering from the gunfire. It was only when she watched the scene in a later broadcast that she realized who it was. Her children said she screamed at the sight, then fainted.[3] She told reporters, "My son didn't die in vain. This was his sacrifice for our homeland, for Palestine."[42] Speaking from hospital, Muhammad's father Jamal said: "I appeal to the entire world, to all those who have seen this crime to act and help me avenge my son's death and to put on trial Israel ..."[47] In another interview, he said his son had died for "the sake of Al-Aqsa Mosque".[42]

The shooting was reported to have had a profound effect on the family. According to Muhammad Mukhamier, a clinical psychologist who was involved in counseling Muhammad's brothers and sisters, the family was severely traumatized by the shooting, and by the intense media attention and the repeated replays of the incident on Palestinian television. The children were described as suffering from the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder—bedwetting, suffering from recurring nightmares, denying that Muhammad had been killed, and becoming more isolated and withdrawn. Many other Palestinian children who had seen the footage on television were reported to be suffering from similar post-traumatic stress, acting out the shooting in their playgrounds or expressing a fear of being killed in the same way.[53]

Muslim world

The Al-Durrah incident had an immediate impact in the Islamic world, galvanizing popular support for the Palestinian uprising.[54] Media outlets said that Israeli forces had murdered al-Durrah and portrayed the incident as archetypal of Israeli brutality; the Palestinian commentator Khalid Amayreh wrote: "The haunting specter of the murder, which, more or less, epitomizes Israel's long standing treatment of the Palestinians, Lebanese and other Arabs ... testifies to the brutal ugliness of the Zionist mentality and its callous disregard for the sanctity of human life".[55] In the days following the shooting, the footage was repeatedly broadcast on Palestinian television along with patriotic songs and calls to arms against the Israeli aggressor.[56] Several cities throughout the Arab world named streets after the boy, including the street in Cairo on which the Israeli embassy is located.[26][57]

Osama bin Laden invoked the al-Durrah affair several times. On October 7, 2001, he warned President George W. Bush that he "must not forget the image of Muhammad al-Durrah and his fellow Muslims in Palestine and Iraq."[58] Two months later, he said that "Slaying children is infamous for being the height of injustice, disbelief and Pharaonic aggression, but the Children of Israel have used the same style against our sons in Palestine. The whole world looked on and witnessed the Israeli soldiers as they killed Muhammad al-Durrah and many like him."[59]

Israel

Ariel Sharon told CBS News that the footage of the shooting was "very hard to see" and "a real tragedy," at the same time noting, "the one that should be blamed is the only one ... that really instigated all those activities, and that is Yasser Arafat."[60]

Three days after the shooting, the Israeli army's chief of operations, Major-General Giora Eiland, said: "This was a grave incident, an event we are all sorry about. We conducted an investigation, and as far as we understand, the shots were apparently fired by Israeli soldiers from the outpost at Netzarim." Eiland noted that the soldiers at the outpost had been shooting from small slits in the wall and did not have a clear field of vision.[61] The Deputy Defense Minister, Ephraim Sneh, told reporters that "it was a mistake which was not caused by intention" to kill and that he lamented the loss of "an innocent life".[62]

The army's deputy chief of staff, Major-General Moshe Yaalon, called the boy's death "heartrending", but also accused the Palestinians of making "cynical use" of children in clashes with Israeli troops.[61] He told France 2 that "The child and his father were between our position and the place from which we were shot at. It is not impossible - this is a supposition, I don't know - that a soldier, due to his angle of vision, and because one was shooting in his direction, had seen someone hidden in this line of fire and may have fired in the same direction."[63]

Major-General Yom Tov Samia, the chief of the army's southern command, told Israel Radio: "I am very, very sorry from deep in my heart about this kid" but added, "we are sure they were not there by accident. They were throwing stones and Molotov cocktails." He said that his troops had fired live ammunition only because they had been attacked "from four or five directions".[64] In an interview with Israeli television, Samia said he believed that the al-Durrahs had not been shot by the Israeli side in the first place: "I have no doubt that the gunfire, as it appears in the television close-up, was not from Israeli soldiers."[1]

Human rights groups

Several international human rights groups criticized Israel in the wake of the al-Durrah shooting. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International issued a joint statement on October 4 2000 expressing grave concern at the high casualty toll and the killing of children and medics.[65] Citing the cameraman's statement that the IDF had killed the boy deliberately, a November 2001 Amnesty International report entitled "Broken Lives — A Year of Intifada" said that photographs taken by journalists showed a pattern of bullet holes indicating that the father and son were targeted by the Israeli post opposite them. AI also stated that, on October 11, 2001, the IDF spokesperson in Jerusalem had shown AI delegates maps to support their case that the al-Durrahs had been hit by Palestinian gunfire.[48] The International Committee of the Red Cross issued a rare protest at the killing of the ambulance driver who was shot dead while trying to rescue the al-Durrahs.[65]

Controversy

The controversy over al-Durrah's death centers on two main areas. There is first of all criticism of the way France 2 shot, edited, broadcast, and described the material. Independently of that, questions have also arisen because neither Palestinian nor Israeli officials conducted a full investigation. No bullets were formally recovered, there was no autopsy, no ballistics tests were conducted at the scene to determine the angle of the shots, and the Israeli army demolished the wall the al-Durrahs were leaning against, thereby destroying forensic evidence.

Footage

What the raw footage showed

The France 2 footage became controversial because Enderlin's report showed only 59 seconds of 27 minutes of raw footage, and did not include the scene of the boy's death. Just over three minutes of footage was provided to other news organizations and to the Israeli army. France 2 provided the footage free of charge to the world's media, saying it did not want to profit from the incident.[26] None of the distributed footage showed the boy being killed.

Charles Enderlin said that he had cut the death scene from his original report, and from the footage supplied to other media, because it showed the boy in his death throes ("agonie"), which he said in an interview with Télérama in October 2000 was "unbearable."[24] In October 2004, in response to criticism that the footage may have been edited inappropriately, executives at France 2 allowed three senior French journalists—Daniel Leconte, a former France 2 correspondent; Dennis Jeambar, the editor-in-chief of L'Express; and Luc Rosenzweig, a former editor-in-chief of Le Monde, and a Metula News Agency (Mena) contributor—to view all 27 minutes of the raw footage.

Shortly after the viewing, Mena's editor-in-chief Stéphane Juffa reported that the footage did not show the boy's death.[27] Leconte and Jeambar wrote about the footage in an article co-authored a few weeks after viewing it, although it was first published five months later on January 25, 2005 by Le Figaro, allegedly only after it had been offered to, and rejected by, Le Monde.[26] In their article, Leconte and Jeambar write that there is no scene in the France 2 footage that shows the child died. They wrote that they did not believe the scene had been staged, but that "this famous 'agony' that Enderlin insisted was cut from the montage does not exist."[26]

They also wrote that the first 20 minutes or so of the film showed young Palestinians "playing at war" for the cameras, falling down as if wounded, then getting up and walking away. They told a radio interviewer that a France 2 official had said "You know it's always like that."[49] In an interview with Cybercast News Service, Leconte said he found France 2's statement disturbing. "I think that if there is a part of this event that was staged, they have to say it, that there was a part that was staged, that it can happen often in that region for a thousand reasons," he said.[26] Leconte did not conclude that the shooting of the boy and his father was faked. He said, "At the moment of the shooting, it's no longer acting, there's really shooting, there's no doubt about that."[49]

In February 2005, France 2 showed the raw footage to New York Times reporter Doreen Carvajal. She writes that the footage of the father and son lasts several minutes, but does not clearly show the child's death. She also writes there is a cut in the scene that France 2 executives say was caused by the cameraman's efforts to preserve a low battery.[26]

On February 15, 2005, Daniel Leconte said that al-Durrah had been shot from the Palestinian position. He said: "The only ones who could hit the child were the Palestinians from their position. If they had been Israeli bullets, they would be very strange bullets because they would have needed to go around the corner."[49] Leconte said that because the pictures had had "devastating" consequences, which included the public lynching of two Israeli soldiers and a rise in antisemitism among French Muslims, France 2 or Enderlin should admit that their report may have been misleading. "Who will say it, I don't know, but it is important that Enderlin or France 2 should say, that on these pictures, they were wrong—they said things that were not reality," he said.[49]

Enderlin's response to criticism

Enderlin responded to Jeambar and Leconte's charges in a January 27, 2005 article in Le Figaro. He wrote that he had said the bullets were fired by the Israelis for a number of reasons: first, he trusted the cameraman who, he said, had worked for France 2 for 17 years. It was the cameraman who made the initial claim during the broadcast, he said, and later had it confirmed by other journalists and sources. The initial Israeli statements also played a role.[34]

Enderlin said "the image corresponded to the reality of the situation, not only in Gaza but also in the West Bank," where, he wrote, in the first month of the Intifada, the IDF had already shot around one million bullets, and killed 118 Palestinians, included 33 children, compared to the 11 Israelis killed. Enderlin attributed these figures to Ben Kaspit of Maariv.[34]

Other footage shot at Netzarim junction

Footage shot by a Reuters cameraman further away from the scene shows the gun battle from a different angle.[66] According to Nidra Poller, writing in Commentary, the Reuters footage shows a jeep driving partway up the road, in sight and within range of the Israeli position, stopping near the barrel and helping to evacuate a man wounded in the right leg, which is also seen in the France 2 footage. Two ambulances are also shown standing within 15 feet of the al-Durrahs, and men run down the road, passing in front of the al-Durrahs. There is no sound of gunfire nor any other evidence of combat activity near the al-Durrahs.[67] According to Ed O'Loughlin of The Age, another video, consisting of "spliced-up" footage shot by France 2 and other unnamed Western agencies, shows Abu Rahma and the al-Durrahs in long shot. Two figures dressed like the al-Durrahs can be seen from several angles, sheltering behind an obstruction, and Abu Rahma is visible taking cover behind a white van parked on the opposite side of the road. An ambulance driver and a Palestinian policeman are shown being killed as they attempt to reach the al-Durrahs. Soldiers in the Israeli army base and Palestinian gunmen are seen exchanging bursts of automatic gunfire from opposite ends of the wall against which the al-Durrahs are sheltering.[33]

Autopsy, bullets, ballistics, injuries

Bullets, bullet holes

No autopsy was performed,[43] and no bullets appear to have been recovered, either at the hospital or at the scene. In an interview with Esther Schapira for Three Bullets and a Child, a 2002 documentary for Germany's ARD channel, Talal Abu Rahma, the cameraman, said that bullets had, in fact, been recovered. He said that Schapira should ask a named Palestinian general about them. The general told Schapira that he had no bullets, and that there had been no Palestinian investigation into the shooting because there was no doubt as to who had shot the boy. "It was the Israeli side who committed this murder," he said.[68] When told the general had no bullets, Abu Rahma said instead that France 2 had collected the bullets at the scene. When questioned about this by Schapira, he replied: "We have some secrets for ourselves ... We cannot give anything ... everything."[68]

Schapira also reported that the wall the al-Durrahs sheltered behind, in which bullet holes are visible in the footage, had been destroyed by the IDF before a ballistics examination could be conducted. [68][69]

Shahaf/Duriel investigation

Nahum Shahaf, a physicist, and Yosef Duriel, an engineer, were informally commissioned by IDF Southern Commander Major General Yom Tov Samia to begin a second investigation of the case. Shortly after the shooting, the IDF acknowledged there was "a high probability" that IDF gunfire had killed al-Durrah. Deputy Chief of Staff Moshe Ya'alon expressed his sorrow over the tragedy, assuming that "the damage to Israel's reputation was irreversible, and knowing it faced the realities of more children dying ..."[70] Senior officers in the Southern Command were allegedly bitter about what they saw as this hasty capitulation, which is why Shahaf and Duriel's offer to help investigate was accepted. The two were already familiar with one another after being involved in attempts to develop alternative theories about the assassination of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995.[70]

The work of the investigators was hampered by Samia's decision to destroy the structures around the junction a week after the shooting to remove any hiding places for snipers. The investigators instead carried out engineering and ballistic tests to try to replicate the circumstances of the shooting, building a replica of the wall and cylinder at a site in the Negev Desert.[71][19] On October 23, 2000, Shahaf and Duriel arranged a re-enactment of the shooting on an IDF shooting range, in front of a CBS 60 Minutes camera crew. Duriel told 60 Minutes that he believed al-Durrah was killed by Palestinian gunmen collaborating with the France 2 camera crew and the boy's father, with the intent of fabricating an anti-Israel propaganda symbol.[70] Samia immediately removed Duriel from the investigation, but Duriel continued to insist that his version was accurate and that the IDF were refusing to publicize it because the results were "explosive".[70]

The results of the investigation were released on November 27, 2000. Samia stated: "A comprehensive investigation conducted in the last weeks casts serious doubt that the boy was hit by Israeli fire. It is quite plausible that the boy was hit by Palestinian bullets in the course of the exchange of fire that took place in the area." IDF Chief of Staff Shaul Mofaz later insisted that this investigation was a private enterprise of Samia's.[72]

The investigation provoked immediate criticism. Some in the media questioned the roles of Shahaf and Duriel, who held no official military or police positions at the time.[9] According to one reporter, neither had forensic or ballistic qualifications or experience,[33] while other reporters dismissed them as conspiracy theorists.[70] A Haaretz editorial said, "it is hard to describe in mild terms the stupidity of this bizarre investigation," concluding that it was so shaky that the Israeli public would never accept its findings. "The fact that an organized body like the IDF, with its vast resources, undertook such an amateurish investigation—almost a pirate endeavor—on such a sensitive issue, is shocking and worrying," Ha'aretz said.[58] Duriel filed a libel suit against Haaretz reader Aharon Hauptman, who in a letter to the editor criticized the investigation based on the newspaper's report. Duriel lost the suit, the court ruling in 2006 that his investigation had been "amateurish, not meticulous, not objective and unprofessional" and had failed to employ scientific methods.[73] Israel Army's chief of staff Shaul Mofaz distanced himself from the investigation, saying it was a private enterprise of Samia's.[74][75][76]

Shahaf presentation

In February 2005, Nahum Shahaf presented a summary of his views in a presentation to the American Academy of Forensic Sciences in New Orleans, making nine key assertions: that ballistic evidence indicated that al-Durrah had not been in the line of fire of the Israeli outpost; that the spread of stone particles caused by the impact of bullets on the wall behind al-Durrah indicated a less oblique angle of fire, consistent with Palestinian positions; that the shooting might have been a deliberate act by the Palestinians; that some of the bullet holes were made artificially after the shooting; that al-Durrah's injuries were more consistent with a knife than a bullet; that the evidence of the doctors was not consistent with photographs of al-Durrah's body, suggesting that the dead boy in the photographs was not al-Durrah; that the body had reached the hospital before the incident was reported to have started; that blood was not visible on the boy's body at Netzarim junction; and that "manufactured incidents" were shown in the television footage.[77]

Questions raised about father's injuries

Questions were raised regarding Jamal al-Durrah's injuries. On December 13, 2007, Israel’s Channel 10 aired an interview with Yehuda David, a doctor at Tel Hashomer hospital, who had treated al-Durah for knife and axe wounds to his arms and legs sustained during a 1994 Palestinian gang attack. David said the scars that were presented as evidence of bullet wounds during the 2000 shooting are, in fact, scars from a tendon repair operation that David carried out in 1994, as they are neat, long and slender.[78][79]

German television investigation

In 2002, the German broadcaster ARD broadcast "Three bullets and a dead child," a film by German journalist Esther Schapira. Schapira said she went into the project believing that the Israelis shot al-Durrah but became otherwise convinced.[19] Her film did not unequivocally conclude that al-Durrah had been killed by Palestinian fire, but it cast significant doubt on the original reports that he was shot by the Israelis.[80][81] In a second film in 2009, Das Kind, der Tod und die Wahrheit ("The Child, the Death, and the Truth"), Schapira suggests two Palestinian boys may have been injured that day, and that the boy who died and was buried may not have been al-Durrah.[82]

"Minimalist" and "maximalist" narratives

Two narratives have emerged, the so-called "minimalist" and "maximalist" narratives. The "minimalist" narrative is that Palestinian gunfire caused al-Durrah's death. The "maximalist" narrative is that the entire incident was a hoax staged for propaganda purposes [83] by the cameraman, the al-Durrahs and other parties.[9] American journalist James Fallows wrote in 2003:

The reasons to doubt that the al-Duras, the cameramen, and hundreds of onlookers were part of a coordinated fraud are obvious. Shahaf's evidence for this conclusion, based on his videos, is essentially an accumulation of oddities and unanswered questions about the chaotic events of the day. Why is there no footage of the boy after he was shot? Why does he appear to move in his father's lap, and to clasp a hand over his eyes after he is supposedly dead? Why is one Palestinian policeman wearing a Secret Service-style earpiece in one ear? Why is another Palestinian man shown waving his arms and yelling at others, as if 'directing' a dramatic scene? Why does the funeral appear — based on the length of shadows — to have occurred before the apparent time of the shooting? Why is there no blood on the father's shirt just after they are shot? Why did a voice that seems to be that of the France 2 cameraman yell, in Arabic, 'The boy is dead' before he had been hit? Why do ambulances appear instantly for seemingly everyone else and not for al-Dura?"[58]

Several groups and individuals in France have kept the issue alive. In Israel, Pierre Lurçat, the president of an association called Liberty, Democracy and Judaism, published statements on the French Jewish Defense League website urging readers to "Come demonstrate against the lies of France 2" and promoting the "Goebbels award" which the JDL was to "award" Charles Enderlin.[84] A protest was held outside the offices of France 2, Enderlin received death threats, and his home had to be guarded by police. He was eventually forced to move.[85]

Philippe Karsenty, a financial consultant, promoted similar claims on his "Media Ratings" website, a media watchdog group. He became so convinced that the original report was faked that he offered €10,000 "to a charity chosen by France 2 if the chain can demonstrate to us and a panel of independent experts, that the 30 September 2000 report shows the death of the Palestinian child." He was later to demand the resignations of Enderlin and France 2's deputy director general, Arlette Chabot,[26] which was to lead to a France 2 lawsuit for defamation.

An Israel-based news website, the Metula News Agency (MENA), also accused France 2 of broadcasting a hoax.[86] MENA's head Stéphane Juffa wrote an article for the Wall Street Journal in 2004 that argued that the al-Durrah shooting was "nothing but a hoax."[87] In 2007, Daniel Seaman, director of the Israeli government press office, said he accepted the "staged theory."[88]

In the U.S., the hoax hypothesis was supported by Richard Landes,[89] a Boston University professor specializing in medieval cultures, and founder and director of the Center for Millennial Studies,[90] studied full footage from other Western news outlets from the day of the shooting, including the pictures of the boy, and concluded that the shooting had probably been faked.[91] He called the footage an example of "Pallywood" cinema, writing: "I came to the realization that Palestinian cameramen, especially when there are no Westerners around, engage in the systematic staging of action scenes."[26] Landes went on to found the website Second Draft, dedicated to gathering evidence on the al-Durrah case and other controversies in journalism.[92]

Legal action

France 2 filed a series of defamation suits against some of its critics in October 2004, to defend itself against the charges that its reporting of the incident had not been accurate. It sought symbolic damages of €1 from each of the defendants, suing them for a "press offence" under the Press Law of 1881.[84] The law obliges the court to determine whether an accusation is defamatory, whether it is being made in good faith and whether a defendant has undertaken at least a basic verification of the source(s) for the accusation. Truth is not an absolute defence and the law forbids the court from investigating the truth of an accusation.[93][94]

Defamation case against Philippe Karsenty

The first of the France 2 lawsuits was against Philippe Karsenty, who was charged with defaming Charles Enderlin's and France 2's honor and reputation on his website, Media-Ratings. Based on reporting by the Israeli Metula News Agency (MENA), Karsenty claimed that Enderlin's original broadcast was fraudulent and called for the dismissal of Chabot and Enderlin. He claimed that the events filmed by the France 2 cameraman had been faked, that al-Dura had not been killed in front of the camera, and that the boy was in fact still alive.

Explaining this suit to the Jerusalem Post, Enderlin said, "I don't mind people elaborating any conspiracy theory about me and France 2 and writing about it. Another French guy even made a fortune by writing a book about 9/11 saying that it was a missile that hit the Pentagon. I can accept any polemic; what is unacceptable is to be publicly insulted and be called a liar. This is why we sued Karsenty, not for his eccentric theories." [63]

Karsenty called four witnesses in his defense, including Professor Richard Landes. The defense was bolstered by support from Sandrine Alimi-Uzan, the procureur de la République (a lawyer appointed by the court to represent the interests of the state), who argued that although Karsenty had defamed Enderlin, it would be in the public interest for him to be exonerated.[84] In fact, because the procureur had argued for an acquittal, it had been widely expected that the verdict would favor Karsenty.

The case was heard before the 17th Chamber of the Correctional Court of Paris on September 7, 2006. In a judgment released on October 19, the court in fact convicted Karsenty of libel, ordering him to pay €1,000 in costs and €1 in damages to the plaintiffs. The presiding judge, Joel Boyer, strongly criticized Karsenty's argument. Claiming that Karsenty had relied on a single source, the judge stated that Karsenty's argument was "primarily based on extrapolations and amalgams, depend[ed] on peremptory assertions of authority which no Israeli official - nor the army, however concerned in the highest degree, nor justice - has granted the least credit." Judge Boyer commented that "the accused, [by] showing in his account, without distance or critical analysis of his own sources, the idea that scenes have been staged for the ends of propaganda has seriously failed to meet the requirements expected of an information professional."[95][96]

Karsenty appeal

Following an appeal by Karsenty, the case was transferred to the 17th Chamber of the Court of Appeal of Paris in November 2007 and a further hearing was held in February 2008. For the first time, the court asked[97] to see the full set of images of the clashes at Netzarim, which according to the cameraman,[31] had totaled 27 minutes. France 2 presented the court with just 18 minutes of footage, stating that the rest had been destroyed because it did not concern this incident.[98] France 2 was represented by the public prosecutor, Antoine Bartoli, who argued that Karsenty had not conducted a "serious investigation" and that his claims were "undoubtedly defamatory".[99][100]

The 18 minutes of footage was shown to a packed courtroom with Enderlin explaining each segment of the footage. According to the Ha'aretz news service, the footage showed "street battles with dozens of people throwing stones and Molotov cocktails at an IDF outpost, an interview with a Fatah official, and the incident involving Mohammed al-Dura and his father in the last minute of the video." The total video of the al-Durrah incident was seen to comprise about one minute of the 18 minute film. It was noted that the boy moved after the cameraman had said he was dead, and that there was no blood on the boy's shirt.[101]

Also for the first time, the court also appointed an independent ballistics expert, Jean-Claude Schlinger, an advisor on ballistic and forensic evidence for the French courts for 20 years.[97] He reviewed the ballistics evidence, including Karsenty's 90-page ballistics report,[102] which concluded that the bullets "could not have come from the Israeli position, from a technical point of view, but only from the direction of the Palestinian position." He also reported "...there is no objective evidence that the child was killed and his father injured. It is very possible, therefore, that it is a case [in which the incident was] staged."[97] In fact, according to his report, there is no evidence that the boy was wounded in his right leg or in his abdomen, as originally reported.

On May 21, 2008, the court overturned Karsenty's earlier libel conviction. It found that while his claims were "undoubtedly damaging [to] the honor and reputation of information professionals", they were nonetheless within the boundaries of permissible expression in the context of media criticism. The judge commented, "it is legitimate for a monitoring agency to investigate the media, because of the impact of the images which were reviewed across the world, [and] on the conditions in which the report was filmed and broadcast." The court ruled that the evidence presented by Karsenty "did not allow it to rule out the opinion of [France 2] professionals", but rejected Bartoli's assertion that Karsenty's evidence was "neither complete nor serious". Although the court did not endorse Karsenty's views, it stated that "the examination of [the] rushes [makes it] no longer possible to dismiss the views of professionals heard during the case" and had put in doubt the authenticity of the original reporting.[11][103]

Karsenty told the press shortly after the verdict was issued: "The verdict means we have the right to say France 2 broadcast a fake news report, that al-Dura's shooting was a staged hoax and that they duped everybody - without being sued".[104][105] In response, France 2 appealed the case to the Cour de cassation, France's highest court.[11]

Aftermath of the legal proceedings

A petition in support of France 2 has been signed by 80 senior French writers and journalists.[106] Elie Barnavi, historian and former Israeli ambassador in France, has criticized the petition and called for an independent inquiry.[107]

Richard Prasquier, President of the Representative Council of Jewish Organisations in France (CRIF) has written to President Nicolas Sarkozy asking for an independent enquiry commission in an attempt to find out the full truth. This commission should include "experts in ballistics, forensic medicine, traumatology and television images,...as well as representatives from France 2."[108]

Karsenty, has launched a libel suit against Canal+, a pay TV company owned by Vivendi SA, claiming the network aired a documentary “depicting me as a manipulative liar. They said I was the same as those who say 9/11 was an inside job.” The second libel suit charges the weekly magazine L’Express with libel for describing him as an ”obsessive nut case and manipulative.”[109]

Other libel cases

The other two lawsuits were brought by France 2 against Pierre Lurçat of the Jewish Defense League and Dr. Charles Gouz, whose blog republished an article by Stéphane Juffa in which Enderlin and France 2 were criticized and accused of disseminating misinformation. Lurçat's case was dismissed on a technicality and Dr. Gouz received a "mitigated judgement" for allowing the word "misinformation" to be used on his blog with respect to France 2 and its staff.[110]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Goldenberg, Suzanne. "Making of a martyr", The Guardian, October 3, 2000.

- ^ "Boy becomes Palestinian martyr", BBC News, October 2, 2000; Children become symbol of struggle, BBC News, November 19, 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f g Orme, William A. (2000). "Muhammad al-Durrah: A Young Symbol of Mideast Violence", The New York Times, October 2 2000.

- ^ "When Peace Died", BBC News, November 17, 2000.

- ^ Schattner, Marius. "Pictures of death of Palestinian child plunge Israel into embarrassment," Agence France Presse, October 1, 2000; 18 minutes of the France 2 raw footage; the al-Durrah incident begins at 01:17:06:09, YouTube, accessed September 18, 2009.

- ^ Rosenthal, John. France: The Al-Dura Defamation Case and the End of Free Speech, World Politics Watch, November 3, 2006.

- ^ Jadallah, Ahmed. "Boy dies in father's arms in Gaza clashes," Reuters, September 30, 2000.

- ^

- "Israeli Army Says Palestinians May Have Shot Gaza Boy", The New York Times, November 27, 2000.

- Patience, Martin. Dispute rages over al-Durrah footage, BBC News, 8 November 2007.

- Hazan, Helen. "Mohammed a-Dura did not die from Israeli gunfire". Yediot Aharonot, March 19, 2002.

- Carvajal, Doreen. "The mysteries and passions of an iconic video frame", The New York Times, February 7, 2005.