Oroonoko

Oroonoko is a short novel (or novella) by Aphra Behn (July 1640 – April 16, 1689), published in 1688, concerning the tragic love of its hero, an enslaved African in Suriname in the 1660s, and the author's own experiences with the new American colony. It is generally claimed (most famously by Virginia Woolf) that Aphra Behn was the first professional female author in English. While this is not entirely true, it is true that Behn was the first professional female dramatist and novelist, as well as one of the first English novelists. Although she had written at least one novel previously, Aphra Behn's Oroonoko is both one of the earliest English novels and one of the earliest by a woman.

Behn worked for Charles II as a spy during the outset of the Second Dutch War, working to solicit a double agent. However, Charles either failed to pay her for her services or failed to pay her all that he owed her, and Behn, upon returning to England needed money. She was widowed and destitute and even spent some time in debtor's prison before scoring a number of successes as an author. She wrote very fine poetry that sold well and was the basis of her fame for the following generation, and she had a number of highly successfully staged plays that established her fame in her own lifetime. In the 1670s, only John Dryden had plays staged more often than Behn. She turned her hand to long prose toward the end of her dramatic career, and Oroonoko was published in the same year as her death at the age of 48.

Plot

Oroonoko is a relatively short novel whose full title is Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave. The novel concerns Oroonoko, the grandson of an African king, who falls in love with Imoinda, the daughter of that king's top general. The king, too, falls in love with Imoinda. He commands that Imoinda become one of his wives (as Behn, like many of the time, combines Arabs and sub-Sahara Africans). After unwillingly spending time in the king's harem (the Otan), Imoinda and Oroonoko plan a tryst with the help of the sympathetic Onal and Aboan. However, they are discovered, and because of her choice, the king has Imoinda sold as a slave. Oroonoko is then tricked and captured by an evil English slaver captain. Both Imoinda and Oroonoko are carried to Surinam, at that time an English colony based on sugarcane plantations, in the West Indies. The two lovers are reunited there, under the new Christian names of Caesar and Clemene, even though Imoinda's beauty has attracted the unwanted desires of the English deputy-governor, Byam.

Oroonoko organizes a slave revolt. The slaves are hunted down by the military forces and compelled to surrender on Byam's promise of amnesty. However, when the slaves surrender, Oroonoko is whipped. To avenge his honor, and to express his natural worth, Oroonoko decides to kill Byam. But to protect Imoinda from violation and subjugation after his death, he decides to kill her. The two lovers discuss the plan, and Imoinda willingly agrees. Oroonoko's love forbids him from killing his dear one and compels him to protect her, but when he stabs her, she dies with a smile on her face. Oroonoko is found mourning by her body and is kept from killing himself, only to be publicly executed. During his death by dismemberment, Oroonoko calmly smokes a pipe and stoically withstands all the pain without crying out.

After the death of Oroonoko, the Dutch take over the colony and deal with the uprising by mercilessly slaughtering the slaves.

The novel is written in a mixture of first and third person, as the narrator relates actions in Africa and portrays herself as a witness of the actions that take place in Surinam. In the novel, the narrator presents herself as a lady who has come to Surinam with her unnamed father, a man scheduled to be the new deputy-governor of the colony. He, however, dies on the voyage from England. The narrator and her family are put up in the finest house in the settlement, in accord with their station, and the narrator's experiences of meeting the indigenous peoples and slaves are intermixed with the main plot of the love of Oroonoko and Imoinda. At the conclusion of the love story, the narrator leaves Surinam for London.

Structurally, there are three significant pieces to the narrative, which does not flow in a strictly biographical manner. The novel opens with a statement of veracity, where the author claims to be writing no fiction and no pedantic history. She claims to be an eyewitness and to be writing without any embellishment or theme, relying solely upon reality. What follows is a description of Surinam itself and the American Indians there. She regards the locals as simple and living in a golden age (the presence of gold in the land being indicative of the epoch of the people themselves). It is only after that that the narrator provides the history of Oroonoko himself and the intrigues of both his grandfather and the slave captain, the captivity of Imoinda, and his own betrayal. The next section is in the narrator's present; Oroonoko and Imoinda are reunited, and Oroonoko and Imoinda meet the narrator and Trefly. The third section contains Oroonoko's rebellion and its aftermath.

Biographical and historical background

Oroonoko is now the most studied of Aphra Behn's novels, but it was not immediately successful in her own lifetime. It sold well, but the adaptation for the stage by Thomas Southerne (see below) made the story as popular as it became. Soon after her death, the novel began to be read again, and from that time onward the factual claims made by the novel's narrator, and the factuality of the whole plot of the novel, have been accepted and questioned with greater and lesser credulity. Because Mrs. Behn was not available to correct or confirm any information, early biographers assumed the first person narrator was Aphra Behn speaking for herself and incorporated the novel's claims into their accounts of her life. It is important, however, to recognize that Oroonoko is a work of fiction and that its first person narrator -- the protagonist -- need be no more factual than Jonathan Swift's first person narrator, ostensibly Gulliver, in Gulliver's Travels, Daniel Defoe's shipwrecked narrator in Robinson Crusoe, or the first person narrator of A Tale of a Tub.

Fact and fiction in the narrator

Researchers today cannot say whether or not the narrator of Oroonoko represents Aphra Behn and, if so, tells the truth. Scholars have argued for over a century about whether or not Behn even visited Surinam and, if so, when. On the one hand, the narrator reports that she "saw" sheep in the colony, when the settlement had to import meat from Virginia, as sheep, in particular, could not survive there. Also, as Ernest Bernbaum, in "Mrs. Behn's 'Oroonoko'" argues, everything substantive in Oroonoko could have come from accounts by William Byam and George Warren that were circulating in London in the 1660s. However, as J.A. Ramsaran and Bernard Dhuiq catalog, Behn provides a great deal of precise local color and physical description of the colony. Topographical and cultural verisimilitude were not a criterion for readers of novels and plays in Behn's day any more than in Thomas Kyd's, and Behn generally did not bother with attempting to be accurate in her locations in other stories. Her plays have quite indistinct settings, and she rarely spends time with topographical description in her stories[1]. Secondly, all the Europeans mentioned in Oroonoko were really present in Surinam in the 1660s. It is interesting, if the entire account is fictional and based on reportage, that Behn takes no liberties of invention to create European settlers she might need. Finally, the characterization of the real life people in the novel does not follow Behn's own politics. Behn was a lifelong and militant royalist, and her fictions are quite consistent in portraying virtuous royalists and put-upon nobles who are opposed by petty and evil republicans/Parliamentarians. Had Behn not known the individuals she fictionalizes in Oroonoko, it is extremely unlikely that any of the real royalists would have become fictional villains or any of the real republicans fictional heroes, and yet Byam and James Bannister, both actual royalists in the Interregnum, are malicious, licentious, and sadistic, while George Marten, a Cromwellian republican, is reasonable, open-minded, and fair[2].

On balance, it appears that Behn truly did travel to Surinam. The fictional narrator, however, cannot be the real Aphra Behn. For one thing, the narrator says that her father was set to become the deputy governor of the colony and died at sea en route. This did not happen to Bartholomew Johnson (Behn's father), although he did die between 1660 and 1664[3]. There is no indication at all of anyone except William Byam being Deputy Governor of the settlement, and the only major figure to die en route at sea was Francis, Lord Willoughby, the colonial patent holder for Barbados and "Suriname." Further, the narrator's father's death explains her antipathy toward Byam, for he is her father's usurper as Deputy Governor of Surinam. This fictionalized father thereby gives the narrator a motive for her unflattering portrait of Byam, a motive that might cover for the real Aphra Behn's motive in going to Surinam and for the real Behn's antipathy toward the real Byam.

It is also unlikely that Behn went to Surinam with her husband, although she may have met and married in Surinam or on the journey back to England. A single woman would not have gone to Surinam, if she was in good standing and socially creditable. Therefore, it is most likely that Behn and her family went to the colony in the company of a lady. As for her purpose in going, Janet Todd presents a strong case for its being spying. At the time of the events of the novel, the deputy governor Byam had taken absolute control over the settlement and was being opposed not only by the formerly republican Colonel George Marten, but also by royalists within the settlement. Byam's abilities were suspect, and it is possible that either Lord Willoughby or Charles II would be interested in an investigation of the administration there.

Beyond these facts, there is little known. The earliest biographers of Aphra Behn not only accepted the novel's narrator's claims as true, but Charles Gildon even invented a romantic liaison between the author and the title character, while the anonymous Memoirs of Aphra Behn, Written by One of the Fair Sex (both 1698) insisted that the author was too young to be romantically available at the time of the novel's events. Later biographers have contended with these claims, either to prove or deny them. However, it is profitable to look at the novel's events as part of the observations of an investigator, as illustrations of government, rather than autobiography.

Models for Oroonoko

As with other elements of the narrator's account, the idea that there was an historical figure named Oroonoko or that there was even a black African slave who led a revolt in English Surinam whom Aphra Behn might have met has been taken seriously by readers, and even scholars, for centuries, and yet the truth of the matter is impossible to ascertain. It has been taken on faith that the real Behn met a real enslaved African prince, but there is no reason for this generosity. In three centuries, no researchers have been able to produce an actual figure who matches Behn's description. Therefore, it is likely that the hero of the novel is a fiction inspired by reality.

One figure who matches aspects of Oroonoko is the white Thomas Allin, a settler in Surinam. Allin was disillusioned and miserable in Surinam, and he was taken to alcoholism and wild, lavish blasphemies so shocking that Governor Byam believed that the repetition of them at Allin's trial cracked the foundation of the courthouse[4]. In the novel, Oroonoko plans to kill Byam and then himself, and this matches a plot Allin had to kill Lord Willoughby and then commit suicide, for, he said, it was impossible to "possess my own life, when I cannot enjoy it with freedom and honour" [5]. He wounded Willoughby and was taken to prison, where he killed himself with an overdose. His body was taken to a pillory,

- "where a Barbicue was erected; his Members cut off, and flung in his face, they had his Bowels burnt under the Barbicue . . . his Head to be cut off, and his Body to be quartered, and when dry-barbicued or dry roasted . . . his Head to be stuck on a pole at Parham (Willoughby's residence in Surinam), and his Quarters to be put up at the most eminent places of the Colony."[6]

Allin, it must be stressed, was a planter, and neither an indentured nor enslaved worker, and the "freedom and honour" he sought was independence rather than manumission. Neither was Allin of noble blood, nor was his cause against Willoughby based on love. Therefore, the extent to which he provides a model for Oroonoko is limited more to his crime and punishment than to his plight. However, if Behn left Surinam in 1663, then she could have kept up with matters in the colony by reading the Exact Relation that Willoughby had printed in London in 1666 and seen in the extraordinary execution a barbarity to graft onto her villain, Byam, from the man who might have been her real employer, Willoughby.

While Behn was in Surinam (1663), she would have seen a slave ship arrive with 130 "freight," 54 having been "lost" in transit. Although the African slaves were not treated differently from the indentured servants coming from England (and were, in fact, more highly valued), their cases were hopeless, and both slaves, indentured servants, and local inhabitants attacked the settlement. There was no single rebellion, however, that matched what is related in Oroonoko. Further, the character of Oroonoko is physically different from the other slaves by being blacker skinned, having a Roman nose, and having straight hair. The lack of historical record of a mass rebellion, the unlikeliness of the physical description of the character (when Europeans at the time had no clear idea of race or an inheritable set of "racial" characteristics), and the European courtliness the character possesses suggests that he is most likely invented wholesale. Additionally, the character's name is artificial. There are names in Yoruba that are similar, but the African slaves of Surinam were from Ghana. Instead of from life, the character seems to come from literature, for his name is reminiscent of Oroondates, a character in La Calprenéde's Cassandra, which Behn had read[7]. Oroondates is a prince of Scythia whose desired bride is snatched away by an elder king. Alternatively, "Oroonoko" is an obvious homophone for the Orinoco River, along which the English settled, and it is possible to see in the character as an allegorical figure for the mismanaged territory itself.

Slavery and Behn's attitudes

The colony of Surinam began importing slaves in the 1650s, since there were not enough indentured servants coming from England for the labor-intensive sugar cane production. In 1662, the Duke of York got a commission to supply 3,000 slaves to the Caribbean, and Lord Willoughby was also a slave trader. For the most part, English slavers dealt with slave-takers in Africa and rarely captured slaves themselves. The story of Oroonoko's abduction is plausible, for such raids did take place, but English slave traders avoided them where possible for fear of accidentally capturing a person who would anger the friendly groups on the coast. Most of the slaves came from the Gold Coast, and in particular from modern-day Ghana.

According to biographer Janet Todd, Behn did not oppose slavery per se. She accepted the idea that powerful groups would enslave the powerless, and she would have grown up with Oriental tales of "The Turk" taking European slaves[8]. The most likely candidate for Aphra Behn's husband is Johan Behn, who sailed on The King David from the German imperial free city of Hamburg[9]. This Johan Behn was a slaver whose residence in London later was probably a result of acting as a mercantile cover for Dutch trade with the English colonies under a false flag. Had Aphra Behn been opposed to slavery as an institution, it is not very likely that she would have married a slave trader. At the same time, it is fairly clear that she was not happy in marriage, and Oroonoko, written twenty years after the death of her husband, has, among its cast of characters, no one more evil than the slave ship captain who tricks and captures Oroonoko.

Todd is probably correct in saying that Aphra Behn did not set out to protest slavery, but however tepid her feelings about slavery, there is no doubt about her feelings on the subject of natural kingship. The final words of the novel are a slight expiation of the narrator's guilt, but it is for the individual man she mourns and for the individual that she writes a tribute, and she lodges no protest over slavery itself. A natural king could not be enslaved, and, as in the play Behn wrote while in Surinam, The Young King, no land could prosper without a king. Her fictional Surinam is a headless body. Without a true and natural leader, a king, the feeble and corrupt men of position abuse their power. What was missing was Lord Willoughby, or the narrator's father: a true lord. In the absence of such leadership, a true king, Oroonoko, is misjudged, mistreated, and killed.

One potential motive for the novel, or at least one political inspiration, was Behn's view that Surinam was a fruitful and potentially wealthy settlement that needed only a true noble to lead it. Like others sent to investigate the colony, she felt that Charles was not properly informed of the place's potential. When Charles gave up Surinam in 1667 with the Treaty of Breda, Behn was dismayed. This dismay is enacted in the novel in a graphic fashion: if the English, with their aristocracy, mismanaged the colony and the slaves by having an insufficiently noble ruler there, then the democratic and mercantile Dutch would be far worse. Accordingly, the passionate misrule of Byam is replaced by the efficient and immoral management of the Dutch. Charles had a strategy for a united North American presence, however, and his gaining of New Amsterdam for Surinam was part of that larger vision. Neither Charles II nor Aphra Behn could have known how correct Charles's bargain was, but Oroonoko can be seen as a royalist's demurral.

Historical significance

Behn was a political writer on the stage and in fiction, and most of her works have distinct, if not didactic, political purposes behind them. The publication of Oroonoko must be seen in its own historical context as well as in the larger literary tradition (see below). According to Charles Gildon, Aphra Behn wrote Oroonoko even with company present, and Behn's own account suggests that she wrote the novel in a single sitting, with her pen scarcely rising from the paper. If Behn travelled to Surinam in 1663-4, she felt no need for twenty-four years to write her "American story" and then felt a sudden and acute passion for telling it in 1688. It is therefore wise to consider what changes were in the air in that year that could account for the novel.

1688 was a time of massive anxiety in English politics. Charles II died, and James II came to the throne. James's purported Roman Catholicism and his marriage to an avowedly Roman Catholic bride roused the old Parliamentarian forces to speak of rebellion again. This is the atmosphere for the writing of Oroonoko. One of the most notable features of the novel is that Oroonoko insists, over and over again, that a king's word is sacred, that a king must never betray his oaths, and that a measure of a person's worth is the keeping of vows. Given that men who had sworn fealty to James were now casting about for a way of getting a new king, this insistence on fidelity must have struck a chord. Additionally, the novel is fanatically anti-Dutch and anti-democratic, even if it does, as noted above, praise faithful former republicans like Trefly over faithless former royalists like Byam. Inasmuch as the candidate preferred by the Whig Party for the throne was William of Orange, the novel's stern reminders of Dutch atrocities in Surinam and powerful insistence on the divine and emanate nature of royalty were likely designed to awaken Tory objections.

Behn's side would lose the contest, and the Glorious Revolution would end with the Act of Settlement 1701, whereby Protestantism would take precedence over sanguinity in the choice of British monarch ever after. Indeed, so thoroughly did the Stuart cause fail that readers of Oroonoko may miss the topicality of the novel.

Literary significance

Claims for Oroonoko's being the "first English novel" are difficult to sustain. In addition to the usual problems of defining the novel in such a way that all examples fit and no non-novels do, Aphra Behn had written at least one novel prior to Oroonoko. The epistolary novel Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and his Sister predates Oroonoko by more than five years. However, Oroonoko is one of the very early novels in English of a particular sort. It possesses a linear plot and follows a biographical model. It is a mixture of theatrical drama, reportage, and biography that is easy to recognize as a novel.

Oroonoko is the first English novel to show Black Africans in a sympathetic manner. At the same time, this novel, even more than William Shakespeare's Othello, is as much about the nature of kingship as it is about the nature of race. Oroonoko is a king, and he is a king whether African or European, and the novel's regicide is devastating to the colony. The plot of the novel is very theatrical, which follows from Behn's previous experience as a dramatist. The language she uses in Oroonoko is far more straightforward than in her other novels, and she dispenses with a great deal of the emotional content of her earlier works. Further, the novel is unusual in Behn's fictions by having a very clear love story without complications of gender roles.

Critical response to the novel has been colored by the struggle over the enslavement of black Africans and the struggle for women's equality. In the 18th century, audiences for Southerne's theatrical adaptation and readers of the novel responded to the love triangle in the plot. Oroonoko on the stage was regarded as a great tragedy and a highly romantic and moving story, and on the page as well the tragic love between Oroonoko and Imoinda, and the menace of Byam, captivated audiences. As the British and American disquiet with slavery grew, Oroonoko was increasingly seen as protest to slavery. Wilbur L. Cross wrote, in 1899, that "Oroonoko is the first humanitarian novel in English." He credits Aphra Behn with having opposed slavery and mourns the fact that her novel was written too early to succeed in what he sees as its purpose (Moulton 408). Indeed, Behn was regarded explicitly as a precursor of Harriet Beecher Stowe. In the 20th century, Oroonoko has been viewed as an important marker in the development of the "noble savage" theme, a precursor of Rousseau and a furtherance of Montaigne, as well as a proto-feminist work[10]. Most recently, Oroonoko has been examined in terms of colonialism and experiences of the alien and exotic (see, for example, the online course on Oroonoko from the University of California Santa Barbara, below).

Recently (and sporadically in the 20th century) the novel has been seen in the context of 17th century politics and 16th century literature. Janet Todd argues that Behn deeply admired Othello, and elements of Othello can be seen in the novel. In Behn's longer career, her works center on questions of kingship quite frequently, and Behn herself took a radical philosophical position. Her works question the virtues of noble blood as they assert, repeatedly, the mystical strength of kingship and of great leaders. The character of Oronooko solves Behn's questions by being a natural king and a natural leader, a man who is anointed and personally strong, and he is poised against nobles who have birth but no actual strength.

Adaptation

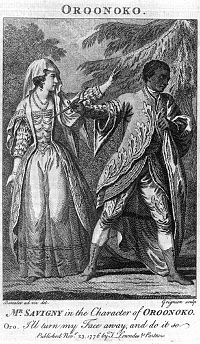

Oroonoko was not a very substantial success at first. The stand-alone edition, according to the English Short Title Catalog online, was not followed by a new edition until 1696. Behn, who had hoped to recoup a significant amount of money from the book, was disappointed. Sales picked up in the second year after her death, and the novel then went through three printings. The story was used by Thomas Southerne for a tragedy entitled Oroonoko: A Tragedy. Southerne's play was staged in 1695 and published in 1696, with a foreword in which Southerne expresses his gratitude to Behn and praises her work. The play was a great success. After the play was staged, a new edition of the novel appeared, and it was never out of print in the eighteenth century afterward. The adaptation is generally faithful to the novel, with one significant exception: it makes Imoinda white instead of black (see Macdonald). As the taste of the 1690s demanded, Southerne emphasizes scenes of pathos, especially those involving the tragic heroine, such as the scene where Oronooko kills Imoinda. At the same time, in standard Restoration theater rollercoaster manner, the play intersperses these scenes with a comic and sexually explicit subplot. The subplot was soon cut from stage representations with the changing taste of the 18th century, but the tragic tale of Oroonoko and Imoinda remained popular on the stage.

Through the eighteenth century, Southerne's version of the story was more popular than Behn's, and in the nineteenth century, when Behn was considered too indecent to be read, the story of Oroonoko continued in the highly pathetic and touching Southerne adaptation. The killing of Imoinda, in particular, was a popular scene. It is the play's emphasis on, and adaptation to, tragedy that is partly responsible for the shift in interpretation of the novel from Tory political writing to prescient "novel of compassion." When Roy Porter writes of Oroonoko, "the question became pressing: what should be done with noble savages? Since they shared a universal human nature, was not civilization their entitlement," he is speaking of the way that the novel was cited by anti-slavery forces in the 1760s, not the 1690s, and Southerne's dramatic adaptation is significantly responsible for this change of focus.[11]

References

- An Exact Relation of The Most Execrable Attempts of John Allin, Committed on the Person of His Excellency Francis Lord Willoughby of Parham. . . . 1665, quoted in Todd.

- Bernbaum, Ernest: Mrs. Behn's 'Oroonoko' in: George Lyman Kittredge Papers. Boston: 1913, pp. 419-433.

- Dhuiq, Bernard: Additional Notes on 'Oroonoko', Notes & Queries 1979, pp. 524-526.

- Macdonald, Joyce Green: Race, Women, and the Sentimental in Thomas Southerne's Oroonoko", Criticism, 40 (1998).

- Moulton, Charles Wells, ed.: The Library of Literary Criticism. vol. II 1639-1729. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1959.

- Porter, Roy: The Creation of the Modern World. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000. ISBN 0-393-32268-8

- Ramsaran, J.A.: "Notes on Oroonoko" Notes & Queries 1960, p. 144.

- Stassaert, Lucienne: De lichtvoetige Amazone. Het geheime leven van Aphra Behn. Leuven: Davidsfonds/Literair, 2000. ISBN 90-6306-418-7

- Todd, Janet: The Secret Life of Aphra Behn. London: Pandora Press, 2000.

- Behn, Aphra. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 19, 2005