Toutatis

Toutatis or Teutates is a Celtic god[1][2][3] who was worshipped in ancient Gaul and Britain. His name means "god of the tribe",[3] and he has been widely interpreted as a tribal protector.[1][4]

Name and nature

Toutatis (pronounced Template:IPA-cel in Gaulish)[5] and its variants Toutatus,[2] Teutates, Tūtatus and Toutorīx,[1] comes from the Gaulish Celtic root toutā, meaning 'tribe' or 'people' (compare Old Irish tuath and the Welsh tud).[1] Thus it means "god of the tribe".[3] Irish mythology mentions the oath formula tongu do dia tongas mo thuath, roughly "I swear by the god by whom my tribe swears".[1]

It is believed Toutatis was an epithet for the tutelary gods of various tribes.[1] Paul-Marie Duval suggests that each tribe had its own Toutatis; he further considers the Gaulish Mars the product of syncretism with the Celtic Toutatis, noting the great number of indigenous epithets under which Mars was worshipped.[4]

Evidence

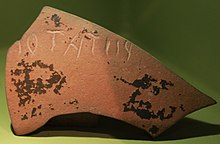

Inscriptions

Inscriptions dedicated to him have been found in Gaul (e.g. at Nîmes and Vaison-la-Romaine in France, and Mainz in Germany),[1] in Britannia (e.g. at York, Old Carlisle, Castor and Hertfordshire),[1][6] in Noricum, and in Rome,[1] among other places.[7] Some of these inscriptions combine his name with other gods such as Mars, Cocidius, Apollo, and Mercurius.[1]

Written evidence

Toutatis is mentioned by the Roman writer Lucan in his epic poem De Bello Civili or Pharsalia. Written in the first century AD, it names Toutatis, Taranis and Esus as three gods to whom the Gauls offered human sacrifices.[1][2][3] In the 4th century commentary on Lucan, Commenta Bernensia, an author added that sacrifices to Toutatis were killed by drowning, and likened Toutatis to Mars or Mercury.[2]

Those who keep watch beside the western shore, have moved their standards home;

The happy Gaul rejoices in their absence; [...]

Now rest the Belgians, and the Arvernian race [...]

Thou, too, oh Treves,

rejoicest that the war has left thy bounds.

Ligurian tribes, now shorn, in ancient days

first of the long-haired nations, on whose necks

once flowed the auburn locks in pride supreme;

And those who pacify with blood accursed,

savage Teutates, Hesus' horrid shrines,

and Taranis' altars, cruel as were those

loved by Diana, goddess of the north.

In his third-century work Divinae Institutiones, Roman writer Lactantius also names Toutatis as a Gaulish god to whom sacrifices were offered.[2]

TOT finger rings

A large number of Romano-British finger rings inscribed with the name "TOT", thought to refer to Toutatis, have been found in eastern Britain, the vast majority in Lincolnshire, but some in Bedfordshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire. The distribution of these rings closely matches the territory of the Corieltauvi tribe.[9] In 2005 a silver ring inscribed DEO TOTA ("to the god Toutatis") and [VTERE] FELIX ([use this ring] happily") was discovered at Hockliffe, Bedfordshire. This inscription confirms that the TOT inscription does indeed refer to the god Toutatis.[10]

In 2012 a silver ring inscribed "TOT" was found in the area where the Hallaton Treasure had been discovered twelve years earlier. Adam Daubney, an expert on this type of ring, suggests that Hallaton may have been a site of worship of the god Toutatis.[11]

Popular culture

- Toutatis is often sworn, 'By Toutatis', by the Gauls in the Asterix franchise.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Koch, John (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1665.

- ^ a b c d e Maier, Bernhard (1997). Dictionary of Celtic Religion and Culture. Boydell & Brewer. p. 36, 263-264.

- ^ a b c d Cunliffe, Barry (2018) [1997]. "Chapter 11: Religious systems". The Ancient Celts (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 275.

- ^ a b Paul-Marie Duval. 1993. Les dieux de la Gaule. Éditions Payot, Paris. ISBN 2-228-88621-1

- ^ Pierre-Yves Lambert (2003). La langue gauloise. Éditions Errance, Paris.

- ^ Collingwood, R.Gh. and Wright, R.P. (1965) The Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB) Vol.I Inscriptions on Stone. Oxford. RIB 1017, online at romaninscriptionsofbritain.org

- ^ Listing for Toutatis from www.arbre-celtique.com.

- ^ "M. Annaeus Lucanus, Pharsalia, book 1, line 396".

- ^ Spicer, Graham (16 July 2007). "Missing Link To Bloodthirsty Ancient Celtic Warrior God Uncovered". Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- ^ "Record ID: BH-C3A8E7 - Roman finger ring". Portable Antiquities Scheme. 3 November 2007. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- ^ "Rare silver ring unearthed near site of Hallaton hoard". 7 August 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

Sources

- British Museum, London, England.

- Lancaster museum, Lancaster, England.

- Newcastle Museum of Antiquities, Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

- Penrith Museum, Penrith, England.

- Vercovicium Roman Museum, Housesteads Fort, Northumberland, England.

- York Castle Museum, York, England.

- M. Almagro‐Gorbea, A. J. Lorrio Alvarado, Teutates: el héroe fundador, Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia, 2011

Further reading

- Clémençon, Bernard; Ganne, Pierre M. "Toutatis chez les Arvernes: les graffiti à Totates du bourg routier antique de Beauclair (communes de Giat et de Voingt, Puy-de-Dôme)". In: Gallia, tome 66, fascicule 2, 2009. Archéologie de la France antique. pp. 153–169. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/galia.2009.3369] ; www.persee.fr/doc/galia_0016-4119_2009_num_66_2_3369

- Lajoye, Patrice; Lemaître, Claude. "Une inscription votive à Toutatis découverte à Jort (Calvados, France)". In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 40, 2014. pp. 21–28. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.2014.2423] ; www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_2014_num_40_1_2423