Étienne Colaud

Étienne Colaud (also Étienne Collault) was a French illuminator and book dealer, active in Paris between 1512 and 1540. A number of surviving archives indicate that he was based on the Île de la Cité, close to the cathedral of Notre-Dame, and that other family members also worked in the book trade. His clientele came from leading families of the time, including great land owners, top prelates, and even the king himself. Using a Book of hours that carries his name, scholars have attributed approximately twenty manuscripts to him by analysing the techniques and style applied. There are also a number of religious books, translations into French from Latin or Italian, chivalric narratives and illuminated texts. Étienne Colaud's style is strongly influenced by his near contemporary, the Parisian illuminator Jean Pichore, but his work indicates that he was also networked with virtually every other Paris book-artist of the period.[1][2]

His parallel business as a book entrepreneur involved the various stages of book production from authorship and bookbinding to the issuing of commissions to copyists and decorators. He had a network of regular and occasional miniaturist artists who provided appropriate illustrations. Their names remain unknown, but they are identified through a series of standard soubriquets such as "exécutant principal des Statuts", "Maître d'Anne de Graville" or "Maître des Puys de Rouen".[1]

Historiography

[edit]The name of Étienne Colaud was first picked out in an archive document by Léon de Laborde in approximately 1850.[3] But it was not till 1889 that Paul Durrieu attributed a complete set of works to Colaud. The works in question were a set of statutes of the Order of Saint Michael, dating from the time of Francis I.[4] Durrieu continued with his studies, and identified more of Colaud's work in 1911.[5] But he also identified a great heterogeneity of styles, which caused him to think that Colaud must have been not merely an illustrator, but also a book seller, and that certain of the miniatures must have been outsourced. Jules Guiffrey completed and published a biographical sketch in 1915 after unearthing further documents in the archives.[6] For most of the rest of the twentieth century art historians paid no further attention to Étienne Colaud. Then in 1997 Myra Orth attributed another manuscript, the "Panégyrique de François Ier", to him. (The attribution to Colaud has subsequently been contested.) A piece of preliminary university-level research by Marie-Blanche Cousseau returned to the "Statutes of the Order of Saint Michael" concluded in 1999 that there had been a "Colaud Group" of illuminators producing the miniatures included in the manuscript.[7] During the first decade of the twenty-first century various further works were attributed to the "Colaud Group". Marie-Blanche Cousseau completed and defended her doctoral dissertation in 2009. In it she identified a significantly greater body of work attributable to the "Colaud Group" than had hitherto been possible. She also, for the first time, differentiated clearly the work of the master from that of his collaborators.[1]

Elements of a biography

[edit]Archival traces

[edit]Several documents, notably accounting records, in the archived include elements from which it is possible to trace or infer aspects of Colaud's life. The earliest surviving mention of him dates back to 1512, which is when his name first appears in a Book of hours. If he was already working as an illustrator if can be inferred that he was born during the final decade of the fifteenth century or earlier. The same Book of hours gives his address as the Rue de la Vieille-Draperie, which places him close to the main entrance of the Palais de la Cité, a former royal palace that had by this time been repurposed as the headquarters for the French Treasury and Justice Service, along with the Paris parlement. More biographical evidence comes from a receipt for payment dated 9 January 1523. This evidences a transaction whereby Colaud was paid 72 Tours pounds for producing six handwritten decorated books containing the chapters, statutes and ordinances of the Order of Saint Michael. A new set of written statutes was most probably required because of a group of knights having recently joined the order. Evidence survives of a further payment in 1528 in respect of a further six books. This time the information included indicates expressly that Colaud had looked after not merely the production and decoration of the books, but also had seen to having them bound and placed in their covers. The speed with which the contract had been fulfilled confirms inferences from other sources that Colaud was by this time also working as a book trade entrepreneur, able to sub-contract some of the work involved in the project. It is likely that he managed the entire process of production, copying, illumination, binding and covering, with each separate process undertaken by a different specialist craftsman. Nevertheless, he was evidently still working as an illuminator himself: on 23 December 1534 he was paid 36 sous by the cathedral chapter for having added gilded initials in four recently copied manuscripts. However, it seems likely that through the 1530s he was undertaking less hands-on illumination work and devoting more time to his entrepreneurial activities, which were very much more lucrative. In a contract of 1540, which he counter-signed simply as a witness, his occupation is given simply as "merchant".[1]

Family

[edit]The last surviving document indicating that Étienne Colaud was still actively engaged in business dates from December 1941. The date of the inventory of his possessions following his death is date June 1542. It is extremely unusual for a notarised inventory of assets at death to be produced for a mere illuminator, and the document carries the information that by the time of his death Colaud had become wealthy, in possession of land in the Paris region, most significantly at Sceaux, outside the city walls to the south. He was also well networked with other significant figures in the book trade, not leastly through his own family connections. His wife, Jeanne Patroullard, who was probably his second wife, died in 1545 and also left a will that has survived. Jeanne Patroullard's own executor was the city book dealer Galliot du Pré. Testamentary records indicate that Étienne Colaud had at least four daughters. The oldest of these, named Claude, married a parchment maker whose premises were in the Rue Saint-Jacques. The fourth daughter, Marie, married the illuminator Martial Vaillant whose business was in the Rue Neuve-Notre-Dame.[8] A certain amount is known about Martial Vaillant: in 1523 he assumed the position of governor with the Fraternity of St. John the Evangelist which was a business association for members of the books trade. At least one Book of hours in the collection of King Francis I is attributed to Vaillant.[1][8]

Customers

[edit]Using both the archive records and the attributions to him found in surviving collections it becomes possible to identify many if Colaud's principal customers, and to gain a sense of the success of his business. The most socially important of his customers was King Francis I who, in addition to the "Statutes of the Order of Saint Michael, probably also commissioned from him an Evangeliary or Gospel Book and a treatise on "The Sufferings of Italy". A member of the king's entourage - possibly his bookish sister Marguerite - ordered a chivalric tale. Others of his aristocratic clientele included William of Montmorency (or his son), Marie d'Albret, Countess of Nevers and Rethel, Anne de Polignac (the wife of Charles de Bueil) and possibly Anne de Graville. Leading churchmen among his customers included Bishops Philippe de Lévis and François de Dinteville. With new technologies appearing, Colaud also worked for printers, decorating prestigious printed works destined for the good and great. An example was Jodocus Badius who entrusted him with the decoration of a printed book produced for Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.[1]

Style of painting

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]The style used in Étienne Colaud's miniatures is defined, in the first instance, according to the only compilation of his work that actually carries his own signature. That is the Book of hours of 1512. Even here, however, it becomes necessary to distinguish between the handiwork of two artists. Four prominent and relatively large miniatures in the book are believed to be the work of an unnamed member of the workshop-studios of Jean Pichore. All the other illustrations, of which there are approximately fifteen, are indeed believed to have been produced by the "Master craftsman" responsible for the creation of the book, clearly identified as Étienne Colaud.[1]

Colaud's art features a clear and distinctive approach to depicting people. Faces are shown with clearly delineated cheek-bones and the frequent re-use of the same compositions and poses. Cheeks are picked out with a pink wash off-setting otherwise pallid grey facial tones. Eye-lids are well-defined. Eyebrows and mouths are finely drawn. Hair is often accented with gold or yellow, highlighting the curls and volume. The artist's eye for detail is also evident in the way he draws his characters' clothes, highlighting the textures and folds in the material. Except in the case of grisaille miniatures, Colaud uses the same relatively restricted range of strong colours, including gold, azure-blue, strong green (vert franc), red, mauve and, more rarely, vibrant orange.[1] Colaud selected from a small range of decorative and quasi-architectural motifs which reappear in a number of his works. One example is the flowers decorating the side-panels of pulpits and thrones, depicting bulging columns imitating marble or acanthus leaves and sometimes, between each, a face.[1]

Colaud's illustrative miniatures are in addition characterised by frequent re-use of the same compositions and poses adopted for the people included in the. As an example, the arrangements of the interiors and the disposition of the kneeling figures in a miniature showing Palamon and Arcite at the feet of Theseus re-appear in a number of his paintings. His version of the Adoration of the Magi also turns up in various works.[1]

Influences

[edit]The style and composition of Colaud's illuminated images was clearly influenced by several of his contemporaries and near contemporaries. Of these, he is closest in approach to the Paris illuminator Jean Pichore. He worked with several members of Pichore's workshop and also reprised some of Pichore's earlier works, leading scholars to speculate that Pichore probably lent him some of his manuscript dossiers in order that Colaud might make copies from the illustrations they contained. For instance, Colaud re-used an image of the "Crowding of the Blessed Virgin Mary" that had made its first (known) appearance in a Book of Hours illustrated by Pichore. Colaud was also influenced - if less directly - by the work produced in Tours by the illuminator Jean Poyer, notably by some of the illustrations appearing in the Book of Hours of Guillaume Briçonnet, which he had most likely encountered only through a copy of it in Pichore's possession. The New York scholar Myra Orth was so struck by the extent to which Colaud's work is influenced by that of Jean Pichore that she suggested that the younger man must have undertaken an apprenticeship or other form of training in the workshop-studios of Pichore. In particular, Orth highlights the way in which the faces of the women incorporated into Colaud's illustrations seem to recall the faces appearing in Pichore's own works.[1][9][10]

He also bases some of his illustrations on miniatures by the Flemish artist Noël Bellemare, with whom, he collaborated on the "Roman de Lérian et Lauréolle".[1] These influences demonstrate that, when it came to artistic style, Colaud continued to nurture close links with the leading Paris-based illuminators of the time. Alone among these, only the anonymous "Maître de François de Rohan" seems not to have enjoyed a relationship of "mutual influence" with Colaud, even though he is believed to have completed (at least) one manuscript that Colaud had started. As for the workshop-studios of the "Maître des Entrées parisiennes", another well-regarded illuminator whose actual name remains unknown, the influence was in the other direction. Scholars adduce a number of instances where work produced by the "Maître des Entrées parisiennes" or his assistants was clearly influenced by the work of Étienne Colaud.[1][6]

The other important influence on Colaud's artistic style comes not from his fellow illuminators but from woodcut engravings of the time. The printed images presented in the books produced by Antoine Vérard reappear in several Colaud illustrations. For instance, the depiction of the Battle of Fornovo included in an edition of "La Mer des histoires", printed by Vérard at Lyon in around 1506, turns up in an illustration of the same title in Colaud's copy of "Mémoires" by the writer-diplomat Philippe de Commines. The frontispiece of "La Victoire du roy contre les Véniciens" printed by Vérard in around 1510, is partially reproduced in Colaud's illustration of the "Vie de saint Jérôme". Colaud also picked up on the 1507 trademark woodcut presentation showing Josse Bade's printing shop "at work", which he included as a miniature in a printed Book of hours. Colaud also found inspiration from beyond the Paris basin, notably from the engravings of Albrecht Dürer whose work, partly due to the technological advances of the time, was already much celebrated across much of Europe, and on both sides of the Rhine. Colaud clearly drew on Dürer's "Birth of the Virgin" from his 1511 "Life of the Virgin" series for his own miniature depicting the birth and baptism of St. Jerome. He also reproduces characters from Dürer's portrayal of "Christ Arrested" in the "Small Passion" in his own depiction of Christ's arrest in the Book of Hours he created for François de Dinteville.[1]

Works attributed

[edit]

Manuscript illuminations in Colaud's hand

[edit]Based on the list created in 2011 by Marie-Blanche Cousseau, there are approximately twenty books in which the illustrations can be attributed to Colaud. The list is remarkably diverse, including not just Books of hours (still a mainstream element in the portfolios of manuscript illuminators in mainland western and central Europe during this period), but also books of liturgy and other religious books, and indeed some secular works. In addition to working with traditional manuscript publications, he contributed illuminated illustrations in high-end prestigious printed books produced for those highest echelons of society, bishops and secular lords alike.[1]

Very often Étienne Colaud collaborated with other illuminators, to such an extent that for a long time it was considered impossible to differentiate between his own hand and the hands of other artists who might have worked with him on the same manuscript volume. There are a number of works which for a long time were believed to be the work of Colaud which, following the painstaking research of Marie-Blanche Cousseau, are now attributed to fellow contributors whose style is close to that of the master. That is the reason why art historians often prefer to talk in terms of the "Colaud group", when not engaging in the question of whether an individual work was produced by Étienne Colaud in person. The works for which Colaud is solely responsible from start to finish are relatively rare.[1] The situation also changed through the period during which he was active. Until the end of the 1520s he was more frequently engaged as a hands-on manuscript illuminator. After that he picked up his quills and pens infrequently, concentrating instead on his work as a book seller and agent allocating manuscripts requiring illumination-illustrations to others.[1]

Manuscript editions of the Statutes of the Order of Saint Michael

[edit]Some of the best known texts associated with Étienne Colaud's illuminations, and indeed some of the best known of his illuminations, are those involving the Statutes of the Order of Saint Michael. The text regulates the functioning of a chivalric order created in 1469 by Louis XI of France and sustained by his successors. The commitment to the order of Francis I of France, who came to the throne in 1515, is of particular note here. Francis, "Father of the Letters", commissioned new illuminated manuscripts of the statutes for a succession of knights received into the order during his watch. Half a millennium later, nineteen of these manuscripts are still listed as included in French or other European collections. Seventeen of these were probably produced in a batch commissioned, on instructions received from the court, by Colaud. It is difficult to determine the identity of each individual knight for whom each manuscript edition was intended, because the volumes seldom include any heraldic indications or written dedications. But it is usually possible to distinguish between the different artists responsible for each of the miniatures with which the manuscripts are decorated. Most of the time, the point of departure will be the relatively large illustration at the front of the manuscript showing the king seated on his throne and surrounded by his knights. Despite his ample qualifications as an illuminator, it is believed that only one of the manuscripts was produced by Colaud in person. The project was important, prestigious and probably urgent. He delegated most of the work to a number of occasional sub-contractors, to whom he probably provided pro formae of some description.[1]

Several of the manuscripts can be grouped with some confidence from their contents and the style of the miniatures incorporated within them.

- There is a group of seven manuscripts identically crafted, both with regard to the text and in terms of the style of the illustrations. Five of these can be attributed to a single artist, identified by Marie-Blanche Cousseau as the "principal producer of the statutes" ("exécutant principal des Statuts"). The other two manuscripts in this group, despite being very close to the first five, Cousseau nevertheless attributes to other craftsmen.[1]

- There is another group of five manuscripts each with identical texts and secondary decorations. A sixth manuscript has been identified which probably served as a model for these five even though it includes a miniature that is slightly different. This group of five plus one manuscripts is attributed to another member of Colaud's group.[1]

- Two other manuscripts stand out for their individual lay-outs: these appear to have been produced according to more prescriptive commissions than the others. One is a copy dated 1527 and produced for the English King Henry VIII. Another, despite being attributed to the Colaud group, is unusual in the extent to which the artist has been influenced by another leading Parisien illuminator of the time Noël Bellemare, originally from Antwerp in Flanders.[1]

Illuminations attributed to members of Colaud's network of assistants and sub-contractors

[edit]"Principal producer of the statutes"

[edit]It is the artist identified by Marie-Blanche Cousseau as "L'exécutant principal des Statuts" who most frequently featured in the listings of identified works from the Colaud circle. In addition to his work on the Statutes of the Order of Saint Michael discussed above, he produced numerous further copies produced for Colaud. But this individual was also producing plenty of work on his own account, and without reference to Colaud, suggesting that he must have had his own studio-workshop staffed by his own team of illuminators. Starting in around 1525 he even took over commissions started by Colaud, apparently managing the production of certain manuscripts, while sharing the hands-on work with a colleague. That appears to have been the approach taken with the Evangelion of Francis I. That turned out to be the first in a succession of commissions carried out under similar circumstances during the 1520s and 1530s.[1]

Many of the miniatures featured repeat forms and compositions already present in the work that this illuminator has previously used in his work for Colaud. One example cited is the "Presentation [of Christ] in the Temple" in the Evangelion at the Sainte-Geneviève Library, which then re-appears in one of the Antiphonaries of Malta. Similarly, "Christ chased from the temple" in the Evangelion of Francis I is re-used in one of the Antiphonaries. Another interesting example is the miniature showing the Court of the Duke of Burgundy in the Mémoires of Philippe de Commines, which closely follows the overall compositions employed in the statutes, while differing from Colaud's work in terms of important stylistic details. The details in question include a number specific to miniatures from the "Principal producer of the statutes", such as the way in which images are framed by bulging columns topped with an ogee arch, and a court-chamber interior intersected with small windows and protected by a courtine wall. Other features characteristic of this illuminator include spherical decorations on then upright supports of the throne, interior walls topped off with decorative friezes and "rollers" on arches framing the subject, especially at the central "keystone" position. His human figures frequently feature exceptionally prominent Adam's apples and faces/heads that are strongly illuminated, apparently by the ambient lighting, around the eyes and the base of the neck.[1]

"Master [illuminator] of the Puys de Rouen"

[edit]The "Master of the Puys de Rouen" (loosely, "... of the Hills of Rouen") was engaged for several projects by Étienne Colaud, notably on the so-called "Rouen Manuscript", the work for which he was the principal illustrator, and from which he acquires the name by which he is generally known by scholars.[11] He was active in Paris between 1520 and 1540. His style is characterised by exaggeratedly square-jawed figures, firm outlines and voluminous architectural framing. In addition to the works he produced for Colaud, several other significant manuscripts are attributed to him, including an Evangelion for the Duprat family, a Book of Hours which recently appeared on the London art market through a dealer called Sam Fogg,[10] and another Book of Hours sold by the specialist dealer "Les Enluminures" in 2008. The German art historian Eberhard König has suggested this last work might be attributed to Henri Laurer, an artist from Paris who moved to Mirepoix (far away, south of Toulouse) but the attribution was not endorsed by other specialist scholars.[1]

"Master [illuminator] of Anne de Graville"

[edit]The "Master of the Puys de Anne of Graville", who was active during approximately the ten years from 1520 till 1530, owes his conventional soubriquet to his participation as one of those who decorated the manuscript of the "Roman de Palamon et Arcita", translated-authored by Anne de Graville.[12] This master's style differs from that of Colaud himself most clearly by the application of softer brush strokes, a less firm approach to outlines and the reduced scale of the people in the images. Myra Orth believed that in addition to his work with Colaud, he also produced a miniature included in a Pontifical Liturgy manuscript for Philippe de Lévis[10]

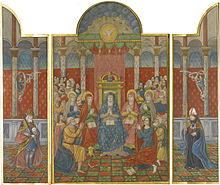

Triptych

[edit]A small triptych painted on vellum durned up in a sale in 2013. The central panel, representing Pentecost, is attributed to Colaud. The image is of the Virgin Mary wearing a lavish Fleur-de-lys robe. The side panels, both of which are attributed to his co-worker known as, the "Master of François de Rohan", feature respectively the Emperor Charlemagne and Saint Augustine of Hippo.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Marie-Blanche Cousseau (1976-2011); Guy-Michel Leproux (revisions in the light of subsequent discoveries) [in French] (2016). Étienne Colaud. Renaissance. Presses universitaires François-Rabelais. ISBN 9782869065437. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Frédéric Elsig. "Etienne Colaud et l'enluminure parisienne sous le règne de François I er (collection «Renaissance») by Marie-Blanche Cousseau". Comptes Rendues ... Review. Librairie Droz (Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance), Genève. JSTOR 44514821. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Musée Condé, Chantilly, Ms. 892

- ^ Paul Durrieu [in French] (1889). "Les manuscrits à peintures de la bibliothèque de sir Thomas Phillipps à Cheltenham". Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes. 50: 381–432. doi:10.3406/bec.1889.447570. hdl:2027/gri.ark:/13960/t09w5vm0v. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Paul Durrieu, Les manuscrits des Statuts de l'ordre de Saint-Michel, Paris, 1911

- ^ a b Jules Guiffrey, Artistes parisiens du XVIe et XVIIe siècles, Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1915, notice 33.

- ^ Marie-Blanche Cousseau, Recherches sur Étienne Collault, enlumineur parisien documenté de 1523 à 1541 (mémoire de DEA sous la direction de Guy-Michel Leproux), École pratique des hautes études, 2000.

- ^ a b Stéphanie Deprouw-Augustin (1 December 2020). "L'illustration des livres d'heures de Tory". Humanisme et arts du livre à la Renaissance, catalogue d’exposition à la Bibliothèque municipale de Bourges. Hal archives ouvertes (Hal-02999024). pp. 6–7, 10–11. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Emeline Sallé Dechou. "Marie-Blanche Cousseau: Étienne Colaud et l'enluminure parisienne sousle règne de François Ier, Tours/Rennes, Presses universitaires François Rabelais, 2016" (PDF). review. Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, Université de Tours. pp. 860–862. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Myra D. Orth, Renaissance Manuscripts: The Sixteenth Century, t. I, Londres, Harvey Miller Publishers, coll. « A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in France », 2015, (ISBN 978-1-872501-30-7), p. 285-286.

- ^ "Ancienne cote : Anc. 7584 : Chants royaux sur la Conception, couronnés au puy de Rouen de 1519 à 1528". Archives et manuscrits. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits, Paris. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Le Hir, Yves (1965). Anne de Graville: Le beau Roman des deux amans Palamon & Arcita et de la belle et sage Emilia. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- ^ "The Pentecost, with St. Augustine of Hippo and Charlemagne, a devotional triptych, illuminated miniatures on vellum [France (Paris), c.1530-40]". Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts. Sotheby's, London. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2021.