Chaconine

| |

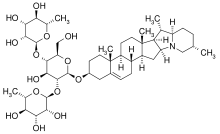

3D model of chaconine using MolView

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Solanid-5-en-3β-yl α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)]-β-D-glucopyranoside

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S,2′S,3R,3′R,4R,4′R,5R,5′R,6S,6′S)-2,2′-{[(2R,3S,4S,5R,6R)-4-Hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-6-{[(2S,4aR,4bS,6aS,6bR,7S,7aR,10S,12aS,13aS,13bS)-4a,6a,7,10-tetramethyl-1,3,4,4a,4b,5,6,6a,6b,7,7a,8,9,10,11,12a,13,13a,13b,14-icosahydro-2H-naphtho[2′,1′:4,5]indeno[1,2-b]indolizin-2-yl]oxy}oxane-3,5-diyl]bis(oxy)}bis(6-methyloxane-3,4,5-triol) | |

| Other names

α-Chaconine, Chaconine

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 77396 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.161.828 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C45H73NO14 | |

| Molar mass | 852.072 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 243 °C (469 °F; 516 K) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[1] | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H361 | |

| P203, P280, P318, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

α-Chaconine is a steroidal glycoalkaloid that occurs in plants of the family Solanaceae. It is a natural toxicant produced in green potatoes and gives the potato a bitter taste.[2] Tubers produce this glycoalkaloid in response to stress, providing the plant with insecticidal and fungicidal properties.[2] It belongs to the chemical family of saponins. Since it causes physiological effects on individual organism, chaconine is considered to be defensive allelochemical.[3] Solanine is a related substance that has similar properties.

Symptoms and treatment

[edit]These are similar to symptoms from ingesting solanine. There are a wide variety of symptoms including: abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache etc.[4]

There is no medicine for detoxification but if it is just after consumption, taking laxatives or gastric lavage could be effective. The symptoms could last several days.

Toxicity

[edit]The presence of more than 20 mg/100g tuber glycoalkaloids is toxic for humans.[5]

There have been instances of fatal poisoning cases from potatoes with high glycoalkaloid content.[6] However, such cases are rare.[7]

Some research shows teratogenic effects on humans, but epidemiological investigations have produced conflicting research, as well.[6] Levels of glycoalkaloids most likely differ by cultivar, storage conditions (especially exposure to sunlight), and processing techniques.[6]

Difference between chaconine and solanine

[edit]Structural difference

[edit]Although α-chaconine and α-solanine are both derived from solanidine, the difference appears in 3 groups attached to the terminal oxygen in solanidine. For α-chaconine, these groups are one D-glucose and two L-rhamnose whereas in α-solanine, they are D-galactose, D-glucose, and L-rhamnose.

Difference in toxicity

[edit]In an experiment demonstrating the feeding-inhibition effect of solanine and chaconine on snails, chaconine had a greater effect than solanine. However, a mixture of chaconine and solanine had a synergistic effect. The mixture had a significantly higher effect of deterred feeding than using solanine and chaconine on their own.[8]

Ratio of ɑ-chaconine to ɑ-solanine in potato

[edit]On average, it is between 1.2 and 2.6 to 1, meaning the amount of ɑ-chaconine is greater than ɑ-solanine.[9] However, the average ratio for the peel was 2.0 whereas that for the flesh was nearly 1.5. Also, the ratio was not consistent and depended on cultivar, growth condition, and method of storage.[9][4]

Research on glycoalkaloids

[edit]Controlling the amount of steroidal glycoalkaloids in Potato

[edit]In 2014, a research group in Japan from the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (or RIKEN) found genes for enzymes that are involved in the synthesis of cholesterol, cycloartanol, and related steroidal glycoalkaloids (SGAs), SSR2. Since SGAs are biosynthesized from cholesterol, restricting those enzymes could reduce the amount of the SGAs in potato.[10]

Level of glycoalkaloids

[edit]The research studied the effects of different cooking techniques on the amount of glycoalkaloids (containing more than 90% of both solanine and chaconine). The techniques studied were boiling, baking, frying, and microwaving. The research found that fried peel has the largest amount of glycoalkaloids (139–145 mg/100g of product), whereas potatoes prepared with other methods contained an average amount of 3 mg/100g product.[6]

Another research found the amount of SGAs is unaffected by baking, boiling, and frying.[11] This research also showed very high level of SGAs with non-peeled potato tubers (200 mg kg^-1 FM).

In 2004, one study that investigated the change in the amount of α-chaconine and α-solanine over 90 days. The result showed how the amount of both α-chaconine and α-solanine did not change significantly if it is kept in a cold and dark place. While the amount varied slightly, the research concluded that it is due to the cultivar.[12]

Treating poisons in potato

[edit]Peels and sprouts usually contain high level of SGAs. Relatively larger amounts can be found if the tuber is exposed to sunlight. If tubers are not matured enough, those might contain high level of chaconine and solanine. Thus, sprouts on potato and peels should be removed and if there are green parts inside the potato, it should be removed as well. It should be preserved in a dark and cold place, but it does not have to be in the fridge. It is likely to germinate or degrade when the surrounding is above 20°C. Heating might not be very effective towards SGAs, therefore, those contain high level of SGAs should be carefully removed.[13][2] Also, if potatoes are kept in a fridge, it increases the amount of sugar. When cooked, such as frying or baking, acrylamide can form.

When cooking potatoes, if it is fried at 210°C for 10 minutes, the amount of solanine and chaconine is reduced to 60% of the original amount. If it is fried at 170°C for 5 minutes, there was no significant change in the amount of solanine and chaconine. However, if it is fried for 15 minutes at the same temperature, solanine decreased to 76.1% and chaconine decreased to 81.5%. Thus, the break down of solanine and chaconine are considered to start around 170°C.[14] In another study, a solution containing α-solanine and α-chaconine is put into boiling water for 150 minutes. The study found no significant decrease in the amount of solanine and chaconine. Therefore, it can be considered that boiling potato is not effective to reduce the amount of solanine and chaconine.[14]

Also, since glycoalkaloids are soluble in water, soaking potatoes in water may cause SGAs to dissolve into the water.[15]

Attempts to make toxin-free potato

[edit]Research was launched in 2015 attempting to make potatoes with no glycoalkaloids by genome editing. Because glycoalkaloids heavily affects human health it is necessary to test for the amount present in potatoes, an expense that would be saved if a glycoalkaloid free potato were available, in addition to being a more healthy food.

Part of the research involves trying to determine what advantage potatoes achieve from producing glycoalkaloids. Research has been published suggesting that potatoes benefit little from the production of glycoalkaloids, though other research have questioned that conclusion.[16][17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "alpha-Chaconine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ a b c Kuiper-Goodman, T.; Nawrot, P.S. "Toxin profile: Solanine and Chaconine IPCS, INCHEM". Archived from the original on 2001-02-25. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ^ Saponins used in traditional and modern medicine. Boston, MA: Springer. 1996. pp. 277–295. ISBN 978-1-4899-1369-2.

- ^ a b McKenzie, Marian; Corrigan, Virginia (1 January 2016). "Chapter 12 - Potato Flavor". Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology (Second Edition): 339–368. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800002-1.00012-1. ISBN 9780128000021.

- ^ Taylor, Mark A.; McDougall, Gordon J.; Stewart, Derek (2007). "Potato Flavour and Texture". Potato Flavor and Texture. pp. 525–540. doi:10.1016/B978-044451018-1/50066-X. ISBN 9780444510181.

- ^ a b c d Bushway, Rodney J.; Ponnampalam, Rathy (July 1981). "a-Chaconine and a-Solanine Content of Potato Products and Their Stability during Several Modes of Cooking". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 29 (4): 814–817. doi:10.1021/jf00106a033.

- ^ "Potato plant poisoning - green tubers and sprouts".

- ^ Smith, David B.; Roddick, James G.; Jones, J.Leighton (May 2001). "Synergism between the potato glycoalkaloids α-chaconine and α-solanine in inhibition of snail feeding". Phytochemistry. 57 (2): 229–234. Bibcode:2001PChem..57..229S. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00034-6. PMID 11382238.

- ^ a b Friedman, Mendel; Levin, Carol E. (2009). "Analysis and Biological Activities of Potato Glycoalkaloids, Calystegine Alkaloids, Phenolic Compounds, and Anthocyanins". Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology: 127–161. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-374349-7.00006-4. ISBN 9780123743497.

- ^ Sawai, S.; Ohyama, K.; Yasumoto, S.; Seki, H.; Sakuma, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Takebayashi, Y.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Aoki, T.; Muranaka, T.; Saito, K.; Umemoto, N. (1 September 2014). "Sterol Side Chain Reductase 2 Is a Key Enzyme in the Biosynthesis of Cholesterol, the Common Precursor of Toxic Steroidal Glycoalkaloids in Potato". The Plant Cell. 26 (9): 3763–3774. doi:10.1105/tpc.114.130096. PMC 4213163. PMID 25217510.

- ^ Finotti, Enrico; Bertone, Aldo; Vivanti, Vittorio (2006). "Balance between nutrients and anti-nutrients in nine Italian potato cultivars". Food Chemistry. 99 (4): 698–701. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.08.046.

- ^ Shindo, T.; Ushiyama, H.; Kan, K.; Yasuda, K.; Saito, K. (2004). "Contents and its Change during Storage of a-Solanine and a-Chaconine in Potatoes". Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. Journal of the Food Hygienic Society of Japan. 45 (5): 277–282. doi:10.3358/shokueishi.45.277. PMID 15678944.

- ^ "Review of Toxicological Literature" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ^ a b Takagi, Kayoko; Toyoda, Masatake; Fujiyama, Yuki; Saito, Yukio (1990). "Effect of Cooking on the Contents of α-Chaconine and α-Solanine in Potatoes". Food Hygiene and Safety Science (Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi). 31: 67–73. doi:10.3358/shokueishi.31.67. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ^ Rytel, Elżbieta (2012). "Changes in the Levels of Glycoalkaloids and Nitrates After the Dehydration of Cooked Potatoes". American Journal of Potato Research. 89 (6): 501–507. doi:10.1007/s12230-012-9273-0.

- ^ Umemoto, Naoyuki. "Is It Possible to Breed Toxin-Free Potato?: Identification and Application of Glycoalkaloid Biosynthetic Genes".

- ^ Sinden, Stephen L.; Sanford, Lind L.; Cantelo, William W.; Deahl, Kenneth L. (1986). "Leptine Glycoalkaloids and Resistance to the Colorado Potato Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Solanum chacoense". Environmental Entomology. 15 (5): 1057–1062. doi:10.1093/ee/15.5.1057. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

External links

[edit] Media related to Chaconine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chaconine at Wikimedia Commons