Marcellina (Gnostic)

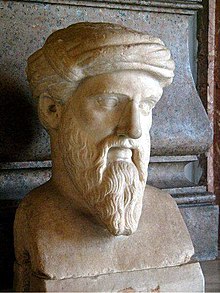

Marcellina was an early Christian Carpocratian religious leader in the mid-second century AD known primarily from the writings of Irenaeus and Origen. She originated in Alexandria, but moved to Rome during the episcopate of Anicetus (c. 157 – 168). She attracted large numbers of followers and founded the Carpocratian sect of Marcellians. Like other Carpocratians, Marcellina and her followers believed in antinomianism, also known as libertinism, the idea that obedience to laws and regulations is unnecessary in order to attain salvation. They believed that Jesus was only a man, but saw him as a model to be emulated, albeit one which a believer was capable of surpassing. Marcellina's community appears to have sought to literally implement the foundational Carpocratian teaching of social egalitarianism. The Marcellians in particular are reported to have branded their disciples on the insides of their right earlobes and venerated images of Jesus as well as Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle. Although the Marcellians identified themselves as "gnostics", many modern scholars do not classify them as members of the sect of Gnosticism.

Historical context

Women played prominent roles in many early Christians sects as prophets, teachers, healers, missionaries, and presbyters.[3] Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany were female followers of Jesus who are mentioned in the gospels and were believed to know the "mysteries" of the kingdom of God.[2] Women like Mary and Martha were the explicit role models for Marcellina and her fellow female preachers.[2] A creed that may have been recited at Christian initiation ceremonies is quoted by the apostle Paul in Galatians 3:28: "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus."[4] In the late first century, Marcion of Sinope (c. 85 – c. 160) appointed women as presbyters on an equal basis as men.[3]

In the second century, the Valentinians, a Gnostic sect, regarded women as equal to men.[3] The Montanists regarded two prophetesses, Maximilla and Prisca, as the founders of their movement.[3] Female religious leaders like Marcellina were not favored by orthodox theologians, who accused them of madness, unchastity, and demonic possession.[2] The Church Father Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240) complained: "These heretical women—how audacious they are! They have no modesty; they are bold enough to teach, to engage in argument, to enact exorcisms, to undertake cures, and, it may be, even to baptize!"[3] He denounced one female religious leader in North Africa as "that viper".[3]

Life and teachings

Carpocratian teachings

As a Carpocratian, Marcellina taught the doctrine of antinomianism, or libertinism,[5][6] which holds that only faith and love are necessary to attain salvation and that all other perceived requirements, especially obedience to laws and regulations, are unnecessary.[5][6] She, like other Carpocratians, believed that the soul must follow the path to redemption, possibly going through many incarnations.[5][6] The goal of the believer is the escape from the cycle of reincarnation by ascending through several stages of deification.[6] The Carpocratians believed that Jesus was only human, not divine,[6] and saw him as an exemplary model to be followed, but an example which a particularly devout believer was capable of surpassing.[5] Jesus's prime virtue was that he could perfectly remember the Divine from his pre-existence.[6] They also venerated Greek philosophers as models to be emulated as well.[6][7] The Marcellians' syncretic cult of images was a natural consequence of this teaching.[5][6] One of the foundational teachings of the Carpocratians was the idea of social egalitarianism, which advocated equality for all people.[8][6] Marcellina's position as the leader of the Carpocratian community in Rome indicates that, for her community at least, this was an idea which was meant to be literally implemented.[8] Some Carpocratians, possibly including Marcellina, held all property in common and shared sexual partners.[6] They also celebrated a form of agape feast.[6]

Adversus Haereses

The Church Father Irenaeus (c. 130 – c. 202) records in his apologetic treatise Adversus Haereses:

Others of them [i.e., the Carpocratians] employ outward marks, branding their disciples inside the lobe of the right ear. From among these also arose Marcellina, who came to Rome under [the episcopate of] Anicetus, and, holding these doctrines, she led multitudes astray. They style themselves Gnostics. They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them. They crown these images, and set them up along with the images of the philosophers of the world that is to say, with the images of Pythagoras, and Plato, and Aristotle, and the rest. They have also other modes of honouring these images, after the same manner of the Gentiles.[11]

Marcellina is the only woman associated with early Gnostic Christianity who is recorded to have been an active religious leader in her own right.[12] Other women such as Helena (allegedly a former Tyrian prostitute turned muse of Simon Magus), Philumena (a prophetess associated with Apelles), and Flora (a student of Ptolemy) are known to have been active as prophetesses, teachers, and disciples involved in sects led by men,[13] but none of them are known to have been leaders themselves.[12] Nonetheless, Marcellina still appears in relation to Carpocrates, a male teacher, who appears to have been more actively involved than her in leading followers, writing treatises, and teaching students.[12] Anne McGuire states that it is unclear whether this description of Marcellina in relation to Carpocrates is a result of Irenaeus's own patriarchal worldview, the actual relationship between her and him, or both.[12]

Marcellina's use of images of Jesus and Greek philosophers would not have been unusual in Roman society at the time, because busts and images of philosophers were common objects of adoration in second-century Roman society.[10][7] While Irenaeus interprets this as a sign of Marcellina's heterodox teaching,[14] to any non-Christian Roman, it would have actually made her seem far less aberrant than "orthodox" Christians.[14] By venerating busts of philosophers and including Jesus among them as the greatest, Marcellina's followers were honoring him in the same way that other philosophers were typically honored throughout the Greco-Roman world.[15] The Carpocratians may have had a more intellectual outlook than other sects,[15] since, according to Clement of Alexandria, Carpocrates's son Epiphanes had been trained in Platonic philosophy.[16][15][17] Nonetheless, Michael Allen Williams states that the veneration of images seems highly unexpected for a supposedly Gnostic sect,[18] since Gnostics are thought to have held the physical body in contempt.[18] He suggests that Marcellina and her followers, like their pagan contemporaries, may have viewed representations of philosophers' physical likenesses as "windows to the soul" and a means of reflecting on the person's teachings.[18] Peter Lampe interprets Marcillina's use of images of famous philosophers as an indication of religious syncretism.[17]

Joan E. Taylor notes that Irenaeus does not state that the Marcellians' portrait of Jesus was inaccurate or that portraits of Jesus were inherently immoral.[15] She also argues that the Marcellians' busts of Jesus and other philosophers may have survived long after their sect declined,[15] observing that, nearly a century later, the Roman emperor Alexander Severus (reigned 222 – 235) is said to have possessed a collection of portrait busts of various philosophers, religious figures, and historical figures including Jesus, Orpheus, Apollonius of Tyana, Alexander the Great, and Abraham.[15] She remarks, "For all we know, one of the many unidentified philosopher busts that exist in today's collections might have been thought of as Jesus in the second–third centuries."[15]

According to David Brakke, the reason why Marcellina and the members of her school identified themselves as "Gnostics" was not as a sectarian identification with the branch of early Christianity known as "Gnosticism",[19] but rather as an epithet for "the ideal or true Christian, the one whose acquaintance with God has been perfected".[20] He notes that Irenaeus himself identifies Marcellina and her sect with the Carpocratians, not with the "Gnostic school of thought".[20] Also, Hippolytus of Rome, who relied on Irenaeus as a source, references that the another sect known as the Naassenes "call themselves 'gnostics' in their own way, as if they alone have drunk from the amazing acquaintance of the Perfect and Good."[19] In the late fourth century, the ascetic monk Evagrius Ponticus described the most advanced stage of Christian asceticism as "the Gnostic",[20] indicating that, despite the association of the word "Gnostic" with Gnosticism, it still retained its original positive meaning in the sense with which Marcellina and her disciples identified.[20] Bentley Layton does not classify Marcellina and her followers as members of the Gnostic sect either.[21]

Contra Celsum

Origen (c. 184 – c. 253) also briefly mentions Marcellina in his Contra Celsum, stating that "Celsus knows also of Marcellians who follow Marcellina, and Harpocratians who follow Salome, and others who follow Mariamme, and others who follow Martha."[9] Anne McGuire states that, because all the other figures listed by Origen in this passage are figures who appear in the canonical gospels, it is possible that the Marcellians may have regarded Marcellina, not only as a teacher and religious leader, but as "an authoritative source of apostolic tradition".[9] Williams notes that Origen seems to have been aware that the Marcellians called themselves Gnostics,[22] since, elsewhere in Contra Celsum, he notes that one of Celsus's arguments against Christianity was the existence of different sects, including ones "who call themselves gnostics".[22] This would presumably include Marcellina and her followers,[22] but Origen refrains from calling them by this term.[22]

Legacy

It is unclear how Marcellina and her followers were regarded by orthodox Christians living in Rome during the 150s and 160s.[23] Irenaeus states that, among members of his own congregation in Gaul in the 180s, "we have no fellowship with them either in doctrine or in morals or in our daily social life",[23] but this statement should not be taken to apply to Christians living in Rome over twenty years prior.[23] Irenaeus also states, "Satan had set forth these people [i.e. Marcellina and her followers] to blaspheme the holy name of the church, so that the [pagan] people turn their ears from the preaching of truth when they hear their different way of teaching and think we Christians are all like them. Indeed, when they see their religiosity, they dishonor us all."[23] He adds that "They misuse the name [Christian] as a mask."[23] This indicates that Marcellina and her Carpocratian followers called themselves "Christians"[23] and, at least to outsiders, her sect appeared to be connected to other branches of Christianity.[23]

Peter Lampe states that it is possible that members of the orthodox community in Rome simply allowed Marcillina and her sect to coëxist,[23] but that it is also possible that they may have actively condemned them.[23] Robert M. Grant identifies the anti-Gnostic writings of Polycarp and Justin Martyr as partially an indirect reaction against Marcellina and her permissive moral teachings.[24] Marcillina and other female prophets like her were consistently portrayed negatively in the histories and canons written by proponents of orthodoxy.[2] According to William H. Brackney, sources indicate that Carpocratians may have continued to exist as late as the fourth century.[6]

References

- ^ Haskins 2005, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b c d e Streete 1999, p. 352.

- ^ a b c d e f Pagels 1989, p. 60.

- ^ Pagels 1989, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e Rudolph 1983, p. 299.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Brackney 2012, p. 75.

- ^ a b Taylor 2018, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b Lampe 2003, p. 319.

- ^ a b c McGuire 1999, p. 260.

- ^ a b c Williams 1996, pp. 107–108, 127.

- ^ Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses Book I, Chapter 25, section 6, translated by Alexander Roberts and William Rambaut

- ^ a b c d McGuire 1999, p. 261.

- ^ McGuire 1999, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b Williams 1996, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e f g Taylor 2018, p. 215.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 3.5.3

- ^ a b Lampe 2003, p. 320.

- ^ a b c Williams 1996, p. 127.

- ^ a b Brakke 2010, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c d Brakke 2010, p. 49.

- ^ Williams 1996, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Williams 1996, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lampe 2003, p. 392.

- ^ Grant 1990, pp. 59–61.

Bibliography

- Brackney, William H. (2012), Historical Dictionary of Radical Christianity, Lanham, Maryland, Toronto, Ontario, and Plymouth, England: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8108-7365-0

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brakke, David (2010), The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-04684-9

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grant, Robert M. (1990) [1989], Jesus After the Gospels: The Christ of the Second Century: The Hale Memorial Lectures of Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, 1989, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox Press, ISBN 0-664-22188-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haskins, Susan (2005) [1993], Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor, New York City, New York: Pimplico, ISBN 1-8459-5004-6

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lampe, Peter (2003), Johnson, Marshall D. (ed.), Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries: From Paul to Valentinus, translated by Steinhauser, Michael, London, England: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., ISBN 0567-080501

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McGuire, Anne (1999), "Women, Gender, and Gnosis in Gnostic Texts and Traditions", in Kraemer, Ross Shepard; D'Angelo, Mary Rose (eds.), Women and Christian Origins, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 257–299, ISBN 0-19-510396-3

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pagels, Elaine (1989) [1979], The Gnostic Gospels, New York City, New York: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-679-72453-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rudolph, Kurt (1983) [1977], Wilson, Robert McLachen (ed.), Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism, Edinburgh, Scotland: T & T Clark, ISBN 0-567-08640-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Streete, Gail Corrington (1999), "Women as Sources of Redemption and Knowledge in Early Christian Traditions", in Kraemer, Ross Shepard; D'Angelo, Mary Rose (eds.), Women and Christian Origins, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 330–355, ISBN 0-19-510396-3

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taylor, Joan E. (2018), What Did Jesus Look Like?, New York City, New York: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, ISBN 978-0-5676-7151-6

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, Michael Allen (1996), Rethinking "Gnosticism": An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 1-4008-0852-9

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)