Music of Somalia

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

The Music of the Somali people is music following the musical styles, techniques and sounds of the Somali people.

Overview

Traditional Somali music

Somali people have a rich musical heritage centered on traditional Somali folklore. Somali songs are pentatonic. That is, they only use five pitches per octave in contrast to a heptatonic (seven note) scale such as the major scale. At first listen, Somali music might be mistaken for the sounds of nearby regions such as Ethiopia, Sudan or the Arabian peninsula, but it is ultimately recognizable by its own unique tunes and styles. Somali songs are usually the product of collaboration between lyricists (lahamiste), songwriters (abwaan), and vocalists (odka or "voice").[1] Dance (ciyaar) also plays a prominent role in Somali musical porformances.[2]

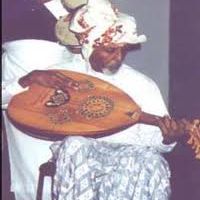

Traditional instruments prominently featured in the music of the northern areas (Somaliland) include the oud lute (kaban). It is often accompanied by small drums and a reed flute in the background. However, heavy percussion and metallic sounds are uncommon in the north.[1] The southern riverine and coastal areas use a wide variety of traditional instruments including:[3][4][5]

- Membranophones: nasaro, mokhoddon and masoondhe (high and heavy drums), reeme, jabbu and yoome (small drums);

- Aerophones: malkad and siinbaar (flutes), sumaari (double clarinet), fuugwo (trumpet) buun, muufe and gees-goodir (horns);

- Idiophones: shagal (metal clappers), shanbaal (wooden clappers), shunuuf (vegetable ankle rattles), tenegyo (xylophone),

- Chordophones: shareero (lyre), kinaandha (lute), madhuube (thumb piano), seese (one-chord violin)

History

The first major form of modern Somali music began in the mid-1930s, when Somaliland was a part of the British Somaliland protectorate. This style of music was known as dhaanto, an innovative, urban form of Somali folk dance and song. This period also saw the rise of the Haji Bal Bal Dance Troupe, which became very influential over the course of its long career.

Somali popular music began with the balwo style, pioneered by Abdi Sinimo, who rose to fame in the early 1940s.[6][7] This new genre then in turn created the Heelo style of Somali music.[8] Abdi's innovation and passion for music revolutionized Somali music forever.[9]

Heellooy

Introduction of melody in modern Somali song is credited to Abdullahi Qarshe, who is recognised for introducing the kaban (oud) as an accompaniment to Somali music and evolving the Balwo of Abdi Sinimo.[10] Qarshe is revered by Somalis as "father of Somali music".[11]

Many qaraami songs from this era are still extremely popular today. This musical style is mostly played on the kaban (oud). Prominent Somali kaban players of the 1950s include Ali Feiruz and Mohamed Nahari.

Political Significance

During the Somali Democratic Republic period, music was suppressed except for a small amount of officially sanctioned music. There were many protest songs (pioneered by the people of Somaliland who were trying to separate and gain independence from the totalitarian neglectful government of Somalia to create their own stable, peaceful government) produced during this period.

Bands such as Waaberi and Horseed have gained a small following outside of the country. Others, like Ahmed Ali Egal, Maryam Mursal and Waayaha Cusub have fused traditional Somali music with pop, rock and roll, bossa nova, jazz, and other modern influences.

Music recorded in the 1970s was preserved in Hargeisa, buried underground, and is now available at the Red Sea Foundation at the Hargeisa Cultural Center, and in Radio Hargeisa. The Barre dictatorial regime effectively nationalised the music scene, with bands and production under state control. Bands were operated by the police, the army and the national penitentiary. Female singers were encouraged more than was the case in most of East Africa. Most musicians had left the country before 1991. Hiddo Dhawr is now operating as the only live music venue in the city.[12]

Music institutions

The first radio station in Somalia to air popular Somali music was Radio Kudu based in Hargeisa, Somaliland. The first song to be broadcast was composed by Guroon Jire in 1940 in English, Somali and Arabic, before being renamed the following year to Radio Somali.[13] The head of the Music department was Mohamed Saeed (Guroon jire). Music is now regularly broadcast on the state-run Radio Mogadishu, as well as a number of private radio and popular television networks such as Horn Cable Television (a private company which is based in Somaliland).

List of Somali musicians

- Aar Maanta

- Abdi Qays

- Abdi Sinimo

- Abdullahi Qarshe

- Ahmed Gacayte

- Ali Feiruz

- Nimco Omer

- Yasminah

- Dur-Dur Band

- Guduuda 'Arwo

- Hasan Adan Samatar

- Hassan Sheikh Mumin

- Jiim Sheikh Muumin

- Khadija Qalanjo

- K'naan

- Magool

- Maryam Mursal

- Mohamed Mooge Liban

- Mohamed Nuur Giriig

- Saado Ali Warsame

- Sulekha Ali

- Waayaha Cusub

- Mohamed Sulayman Tubeec

- Hudeidi

- Uniquegodx

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Abdullahi, pp.170-171

- ^ Congress, International Musicological Society (1990). "Theory" (English) and Lehre (German) versus Téori (Indonesian). EDT srl. ISBN 978-88-7063-084-8.

- ^ Somali Culture and Folklore (1974) pp.63-64

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Somalia (2003) p. 166

- ^ The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. p.57-58

- ^ African Language Review, Volume 6. The University of Michigan: F. Cass. 1967. p. 5.

- ^ Andrzejewski, B. W.; Pilaszewicz, S.; Tyloch, W. (1985-11-21). Literatures in African Languages: Theoretical Issues and Sample Surveys. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521256469.

Cabdi Deeqsi, who created a genre of love poetry called Balwo

- ^ Johnson, John William (1996). Heelloy: Modern Poetry and Songs of the Somali. Indiana University Press. ISBN 1874209812.

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003-02-25). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780810866041.

- ^ Brinkhurst, Emma (2012). Music, Memory and Belonging: Oral Tradition and Archival Engagement Among the Somali Community of London's King's Cross. University of London. p. 61.

- ^ Farah, Gamute (2018-10-28). Coming of Age: An Introduction to Somali Metrics. Ponte Invisible (Redsea Cultural Foundation). ISBN 9788888934471.

- ^ "Uncovering Somalia's forgotten music of the 1970s". Al Jazeera. 18 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Journal of the Anglo-Somali Society, Issues 30-33. Anglo-Somali Society. 2001. p. 56. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

References

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and customs of Somalia. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Mogadishu, Somalia (1974). Somali Culture and Folklore

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003) Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4344-7

- Puchowski, Douglas (2013). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 1. Routledge, ISBN 9781136095702