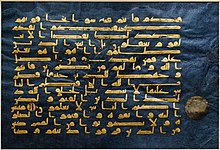

Blue Quran

The Blue Qur'an (Template:Lang-ar) is a second half 9th-mid-10th century - written in Kufic calligraphy, copied in Islamic Iberia in the mid-9th century.[1] It is among the most famous works of Islamic calligraphy,[2] and has been called "one of the most extraordinary luxury manuscripts ever created."[3] Art historian Yasser Tabbaa wrote that the "evanescent effect" of the gold lettering on indigo "appears to affirm the Mu'tazili belief in the created and mysterious nature of the Word of God."[4]

History

The codex has also been dated as late as 1020 CE and placed in Córdoba as well as Qairawan.[5] According to some researchers, the Blue Qur'an is also one of the only extant Fatimid Qur'ans.[4] However, at the moment, the comparison with the Latin Bible of Danila, preserved at Cava de' Tirreni (Italy) but produced in Spain, offers a number of material connections (the deep blue parchment, the ruling, and the use of gold ink) rather suggesting a Spanish origin. Even older Quranic manuscripts are the Sana'a manuscript,[6] Samarkand Kufic Quran,[7] and Topkapi manuscript.[8] It is written in gold and decorated in silver (that has since oxidized) on vellum colored with indigo, a unique aspect of a Quranic manuscript, probably emulating the purple parchment used for Byzantine Imperial manuscripts.[2][9] Red ink is also used.[10]

A Maghribi script Qur'an manuscript written in gold on blue paper has been dated to the 13th or 14th century, inviting comparison to the Blue Qur'an. The Maghribi manuscript's parchment is a lighter tone than the Blue Qur'an and is more heavily decorated, having a foliage motif throughout.[11]

The manuscript's approximately 600 pages[11] were dispersed during the Ottoman period; today most of it is located in the National Institute of Art and Archaeology Bardo National Museum in Tunis, with detached folios in museums worldwide.[10][12] These institutions include the Musée de la Civilisation et des Arts Islamiques in Raqqada, which has 67 folios.[11] The folios are differently sized: the folio held by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is 28.25 cm by 37.46 cm,[10] but there are pages as large as 31 cm by 41 cm.[11] Most of the folios remained in Qairawan until the 1950s, when they were further dispersed.[13] In 2012 and 2013, folios from the Blue Qur'an were sold in major Islamic art auctions, carrying a price of hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece. Christie's of London sold folios in 2012.[14] Sotheby's auctioned off one folio in 2010 for a reported £529,250, a record-breaking sum and over double the low estimate for the lot.[15]

Form

Each sura's verses are demarcated in groups of 20 with silver rosettes[12] and the text itself is inked in gold; the precious metallic text and rich indigo might have been a way for the Fatimid dynasty, which controlled North Africa at the time, to display its wealth, power, and religion in the face of the Byzantine Empire, which controlled Anatolia,[2] and used gold or silver ink on purple parchment for its most lavish manuscripts. The gold ink was created by grinding gold and suspending it in a solution.[3] The surrounding decoration of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Cordoba is similar to and might have been the model for the Blue Qur'an's design.[2][12] Contemporaneous manuscripts were often written on dyed parchment, particularly saffron-colored parchment, a holdover from the pre-Islamic time. Though the method by which the Blue Qur'an was dyed remains unknown, Ibn Badis related the two contemporaneous methods of dying: dip-dying after the parchment was smoothed, or adding dye during the parchment production process.[16] Given the brilliance of the color, it is likely that the parchment was dip-dyed before it was cured, impregnating it with the pigment.[17]

The Kufic script has sharp angles and is written in groups of 15 lines per page with no vowel markings, common characteristics in 9th- and 10th-century Islamic manuscripts.[4][12] The comparatively large number of lines on each page deviates from the norm of other contemporaneous Qur'ans, such as the Amajur Qur'an, that dictated three lines per horizontal page.[18] A column of letters is perceptible on the right side of each folio, created by the insertion of spaces called caesurae that put single letters at the beginnings of lines.[12] Words with unconnected letters are occasionally split between lines in the manuscript, another common feature of Qur'ans from this period.[19] The spacing of the letters has been described as "almost musical" and as "visual rhythm" by Robert Hillenbrand.[5] Another unusual feature of this manuscript is visible mastara lines on some pages, used by the calligrapher to place the text.[20]

Controversy of Origin

The exact origin of the Blue Qur'an still remains hotly debated. Scholars have argued that the Blue Qur'an has originated in various locations, ranging from Iran, Iraq, Tunisia, Spain, to Sicily. These scholars have argued it was possibly created under one of (but not limited to) the following dynasties: Abbasids, Fatimids, Aghlabids, Umayyads, or Kalbids.[21]

Frederick R. Martin, a Swedish man, introduced the Blue Qur'an to the academic community. He claimed that he obtained some of the manuscript's pages in Constantinople, and that it originated in Mashhad, Persia. The Blue Qur'an is connected to Persia through a Persian customs stamp on one its pages, but it is possible only this one page passed through Persia and that it was not necessarily created there.[22] The horizontal layout of the Blue Qur'an resembles the luxurious Qur'ans created during the early Abbasid period, which supports the theory that it was created during the ninth century. If this manuscript was created during or around the Abbasid period, it would be likely that it originated in or around modern day Iraq, since this was the Abbasid's center.[23] These pieces of evidence support the idea that the Blue Qur'an was created in the Eastern Islamic world, as opposed to the Western Islamic world.

On the other hand, the Blue Qur'an was possibly mentioned in the Kairouan library's catalogue around 1300 CE, so it is likely that the Blue Qur'an was in Tunisia at that point in time. This does not confirm that it was created in Tunisia though; it could have been transported there though some scholars argue that it is unlikely that a large, important manuscript like this would be carried such a long distance.[22][24]

The Blue Qur'an shares many characteristics with the Bible of Cava (especially its deep blue color), a manuscript created in 812 CE in Spain. These similarities could imply the Bible of Cava and the Blue Qur'an share their origins in Spain around the ninth century. It is possible that an Umayyad patron or caliph commissioned the Blue Qur'an in Spain, and this manuscript was actually created by Christians, who have a tradition of writing their sacred texts on dyed parchment. Spain is a lot closer to Tunisia than Persia would have been, so the Blue Qur'an's transportation to Tunisia would have been easier in this case.[25]

The controversy of the Blue Qur'an's origin affects scholars even today. For example, even museums cannot agree on how to categorize the Blue Qur'an. The David Collection categorizes this manuscript under Islamic Art and North Africa,[26] while the Denver Art Museum categorizes it as Asian Art while still acknowledging it may have origins in North Africa.[27] This conflicting categorization reflects on how scholars still do not, and may never agree on where the Blue Qur'an really came from.

References

- ^ D'Ottone Rambach, Arianna (January 2017). "The Blue Koran. A Contribution to the Debate on its Possible Origin and Date". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 8 (2). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 127–143. doi:10.1163/1878464X-00801004. S2CID 192957200.

- ^ a b c d "Folio from the "Blue Qur'an" - second half 9th–mid-10th century". Metmuseum.org. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Folio From the Blue Qur'an". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Tabbaa, Yasser (1991). "The Transformation of Arabic Writing: Part I, Qur'ānic Calligraphy". Ars Orientalis. 21. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan: 119–148. JSTOR 4629416.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand, Robert (1999). Islamic Art and Architecture. Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7.

- ^ Dreibholz, Ursula (1999). "Preserving a Treasure: The Sana'a Manuscripts" (PDF). Museum International. 51 (3). UNESCO: 21–25. doi:10.1111/1468-0033.00212.

- ^ "Tashkent's hidden Islamic relic". BBC News. 5 January 2006. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ "Al-Mushaf Al-Sharif Attributed to 'Uthman bin 'Affan". IRCICA. 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Calligraphy". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ a b c "Folio from the Blue Quran". Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d George, Alain (1 January 2009). "Calligraphy, Colour and Light in the Blue Qur'an" (PDF). Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 11: 75–125. doi:10.3366/E146535910900059X.

- ^ a b c d e "Bifolium from the Blue Qur'an". Aga Khan Museum. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Soucek, Priscilla P. (Spring–Summer 1999). "The Abbasid Tradition: Qur'ans of the 8th to the 10th Centuries A.D., The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, vol. 1 by François Déroche (book review)". Studies in the Decorative Arts. 6 (2). University of Chicago Press: 131. doi:10.1086/studdecoarts.6.2.40662688. JSTOR 40662688.

- ^ "Une page du Coran à la vente aux enchères Christie's de Londres". agence Internationale de Presse Coranique. 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ "Sotheby's Islamic Art Sales Series Achieves Record Sum of £25.3 ($40.3) Million". artdaily.org. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Paper". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ Fantar, Muhammad (1982). De Carthage à Kairouan: 2000 ans d'art et d'histoire en Tunisie. AFAA. p. 241.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (1997). Islamic Arts. Phaidon Press Limited. p. 73. ISBN 0-7148-3176-X.

- ^ Blair, Sheila (2004). "Ivories and Inscriptions from Islamic Spain". Oriente Moderno. 23 (84) (2). Istituto per l'Oriente C. A. Nallino: 375–386. doi:10.1163/22138617-08402003. JSTOR 25817938.

- ^ "Calligraphic Tradition in Islam: Bifolium of the 'Blue Qur'an'". The Institute of Ismaili Studies. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ George, A 2009, 'Calligraphy, Colour and Light in the Blue Qur'an', Journal of Qur’anic Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 75-80. https://doi.org/10.3366/E146535910900059X

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M. (2015-01-01). "The Blue Koran Revisited". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 6 (2–3): 196–218. doi:10.1163/1878464X-00602005. ISSN 1878-4631.

- ^ George, Alain (2017-06-20), Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru (eds.), "The Qurʾan, Calligraphy, and the Early Civilization of Islam", A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 120–121, doi:10.1002/9781119069218.ch4, ISBN 978-1-119-06921-8, retrieved 2020-11-08

- ^ George, Alain (April 2009). "Calligraphy, Colour and Light in the Blue Qur'an". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 11 (1): 79–80. doi:10.3366/E146535910900059X. ISSN 1465-3591.

- ^ D’Ottone Rambach, Arianna (2017-01-01). "The Blue Koran. A Contribution to the Debate on Its Possible Origin and Date". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 8 (2): 127–143. doi:10.1163/1878464X-00801004. ISSN 1878-4631.

- ^ "North Africa, Middle East and Iran as", Islamic Art Collections, Routledge, pp. 58–61, 2013-09-05, doi:10.4324/9780203036907-23, ISBN 978-0-203-03690-7, retrieved 2020-12-07

- ^ "Qur'an leaf in Kufic script | Denver Art Museum". www.denverartmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-12-07.