Stingray

| Stingrays Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Bluespotted ribbontail ray (female) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Suborder: | Myliobatoidei |

| Families | |

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae (deepwater stingray), Urolophidae (stingarees), Urotrygonidae (round rays), Dasyatidae (whiptail stingrays), Potamotrygonidae (river stingrays), Gymnuridae (butterfly rays), and Myliobatidae (eagle rays).[1][2]

Stingrays are common in coastal tropical and subtropical marine waters throughout the world. Some species, such as Dasyatis thetidis, are found in warmer temperate oceans, and others, such as Plesiobatis daviesi, are found in the deep ocean. The river stingrays, and a number of whiptail stingrays (such as the Niger stingray), are restricted to fresh water. Most myliobatoids are demersal (inhabiting the next-to-lowest zone in the water column), but some, such as the pelagic stingray and the eagle rays, are pelagic.[3]

There are about 220 known stingray species organized into ten families and 29 genera. Stingray species are progressively becoming threatened or vulnerable to extinction, particularly as the consequence of unregulated fishing.[4] As of 2013, 45 species have been listed as vulnerable or endangered by the IUCN. The status of some other species is poorly known, leading to their being listed as data deficient.[5]

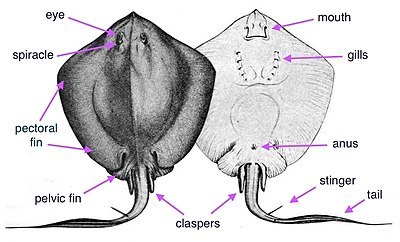

Anatomy

External anatomy of a male stingray

The teeth are modified placoid scales.

Jaw and teeth

The mouth of the stingray is located on the ventral side of the vertebrate. Stingrays exhibit hyostylic jaw suspension, which means that the mandibular arch is only suspended by an articulation with the hyomandibula. This type of suspensions allows for the upper jaw to have high mobility and protrude outward.[6] The teeth are modified placoid scales that are regularly shed and replaced.[7] In general, the teeth have a root implanted within the connective tissue and a visible portion of the tooth, is large and flat, allowing them to crush the bodies of hard shelled prey.[8] Male stingrays display sexual dimorphism by developing cusp, or pointed ends, to some of their teeth. During mating season, some stingray species fully change their tooth morphology which then returns to baseline during non-mating seasons.[9]

Spiracles

Spiracles are small openings that allow some fish and amphibians to breathe. Stingray spiracles are openings just behind its eyes. The respiratory system of stingrays is complicated by having two separate ways to take in water to utilize the oxygen. Most of the time stingrays take in water using their mouth and then send the water through the gills for gas exchange. This is efficient, but the mouth cannot be used when hunting because the stingrays bury themselves in the ocean sediment and wait for prey to swim by.[10] So the stingray switches to using its spiracles. With the spiracles, they can draw water free from sediment directly into their gills for gas exchange.[11] These alternate ventilation organs are less efficient than the mouth, since spiracles are unable to pull the same volume of water. However, it is enough when the stingray is quietly waiting to ambush its prey.

The flattened bodies of stingrays allow them to effectively conceal themselves in their environments. Stingrays do this by agitating the sand and hiding beneath it. Because their eyes are on top of their bodies and their mouths on the undersides, stingrays cannot see their prey after capture; instead, they use smell and electroreceptors (ampullae of Lorenzini) similar to those of sharks.[12] Stingrays settle on the bottom while feeding, often leaving only their eyes and tails visible. Coral reefs are favorite feeding grounds and are usually shared with sharks during high tide.[13]

Behavior

Reproduction

During the breeding season, males of various stingray species such as Urolophus halleri, may rely on their ampullae of Lorenzini to sense certain electrical signals given off by mature females before potential copulation.[14] When a male is courting a female, he follows her closely, biting at her pectoral disc. He then places one of his two claspers into her valve.[15]

Reproductive ray behaviors are associated with their behavioral endocrinology, for example, in species such as Dasyatis sabina, social groups are formed first, then the sexes display complex courtship behaviors that end in pair copulation which is similar to the species Urolophus halleri.[16] Furthermore, their mating period is one of the longest recorded in elasmobranch fish. Individuals are known to mate for seven months before the females ovulate in March. During this time, the male stingrays experience increased levels of androgen hormones which has been linked to its prolonged mating periods.[17] The behavior expressed among males and females during specific parts of this period involves aggressive social interactions.[18] Frequently, the males trail females with their snout near the female vent then proceed to bite the female on her fins and her body.[19] Although this mating behavior is similar to the species Urolophus halleri, differences can be seen in the particular actions of Dasyatis sabina. Seasonal elevated levels of serum androgens coincide with the expressed aggressive behavior, which led to the proposal that androgen steroids start, indorse, and maintain aggressive sexual behaviors in the male rays for this species which drives the prolonged mating season. Similarly, concise elevations of serum androgens in females has been connected to increased aggression and improvement in mate choice. When their androgen steroid levels are elevated, they are able to improve their mate choice by quickly fleeing from tenacious males when undergoing ovulation succeeding impregnation. This ability affects the paternity of their offspring by refusing less qualified mates.[20]

Stingrays are ovoviviparous, bearing live young in "litters" of five to 13. During this period, the female's behavior transitions to support of her future offspring. Females hold the embryos in the womb without a placenta. Instead, the embryos absorb nutrients from a yolk sac, and after the sac is depleted, the mother provides uterine "milk".[21] After birth, the offspring generally disassociate from the mother and swim away, having been born with the instinctual abilities to protect and feed themselves. In a very small number of species, like the freshwater whipray (Himantura chaophraya), the mother "cares" for her young by having them swim with her until they are one-third of her size.[22]

At the Sea Life London Aquarium, two female stingrays delivered seven baby stingrays, although the mothers have not been near a male for two years. This suggests some species of rays can store sperm then give birth when they deem conditions to be suitable.[23]

Locomotion

The stingray uses its paired pectoral fins for moving around. This is in contrast to sharks and most other fish, which get most of their swimming power from a single caudal (tail) fin.[24][25] Stingray pectoral fin locomotion can be divided into two categories: undulatory and oscillatory.[26] Stingrays who use undulatory locomotion have shorter thicker fins for slower motile movements in benthic areas.[27] Longer thinner pectoral fins make for faster speeds in oscillation mobility in pelagic zones.[26] Visually distinguishable oscillation has less than one wave going, opposed to undulation having more than one wave at all times.[26]

Feeding behavior and diet

Stingrays use a wide range of feeding strategies. Some have specialized jaws that allow them to crush hard mollusk shells,[28] whereas others use external mouth structures called cephalic lobes to guide plankton into their oral cavity.[29] Benthic stingrays (those that reside on the sea floor) are ambush hunters.[30] They wait until prey comes near, then use a strategy called "tenting".[31] With pectoral fins pressed against the substrate, the ray will raise its head, generating a suction force that pulls the prey underneath the body. This form of whole-body suction is analogous to the buccal suction feeding performed by ray-finned fish. Stingrays exhibit a wide range of colors and patterns on their dorsal surface to help them camouflage with the sandy bottom. Some stingrays can even change color over the course of several days to adjust to new habitats. Since their mouths are on the side of their bodies, they catch their prey, then crush and eat with their powerful jaws.Like its shark relatives, the stingray is outfitted with electrical sensors called ampullae of Lorenzini. Located around the stingray's mouth, these organs sense the natural electrical charges of potential prey. Many rays have jaw teeth to enable them to crush mollusks such as clams, oysters, and mussels.

Most stingrays feed primarily on mollusks, crustaceans, and occasionally on small fish. Freshwater stingrays in the Amazon feed on insects and break down their tough exoskeletons with mammal-like chewing motions.[32] Large pelagic rays like the Manta use ram feeding to consume vast quantities of plankton and have been seen swimming in acrobatic patterns through plankton patches.[33]

Stingray injuries

Stingrays are not usually aggressive and ordinarily attack humans only when provoked, such as when a ray is accidentally stepped on.[34] Contact with the stinger causes local trauma (from the cut itself), pain, swelling, muscle cramps from the venom, and later may result in infection from bacteria or fungi.[35] The injury is very painful, but seldom life-threatening unless the stinger pierces a vital area.[34] The barb usually breaks off in the wound, and surgery may be required to remove the fragments.[36]

Fatal stings are very rare.[34] The death of Steve Irwin in 2006 was only the second recorded in Australian waters since 1945.[37] The stinger penetrated his thoracic wall and pierced his heart, causing massive trauma and bleeding.[38]

Venom

The venom of the stingray has been relatively unstudied due to the mixture of venomous tissue secretions cells and mucous membrane cell products that occurs upon secretion from the spinal blade. Stingrays can have anywhere between one and three blades. The spine is covered with the epidermal skin layer. During secretion, the venom penetrates the epidermis and mixes with the mucus to release the venom on its victim. Typically, other venomous organisms create and store their venom in a gland. The stingray is notable in that it stores its venom within tissue cells. The toxins that have been confirmed to be within the venom are cystatins, peroxiredoxin, and galectin.[39] Galectin induces cell death in its victims and cystatins inhibit defense enzymes. In humans, these toxins lead to increased blood flow in the superficial capillaries and cell death.[40] Despite the number of cells and toxins that are within the stingray, there is little relative energy required to produce and store the venom.

The venom is produced and stored in the secretory cells of the vertebral column at the mid-distal region. These secretory cells are housed within the ventrolateral grooves of the spine. The cells of both marine and freshwater stingrays are round and contain a great amount of granule-filled cytoplasm.[41] The cells of marine stingrays are located only within these lateral grooves of the stinger.[42] The cells of freshwater stingray branch out beyond the lateral grooves to cover a larger surface area along the entire blade. Due to this large area and an increased number of proteins within the cells, the venom of freshwater stingrays has a greater toxicity than that of marine stingrays.[41]

As food

Rays are edible, and may be caught as food using fishing lines or spears. Stingray recipes abound throughout the world, with dried forms of the wings being most common. For example, in Malaysia and Singapore, stingray is commonly grilled over charcoal, then served with spicy sambal sauce, or soy sauce. Generally, the most prized parts of the stingray are the wings, the "cheek" (the area surrounding the eyes), and the liver. The rest of the ray is considered too rubbery to have any culinary uses.[43]

The Pastel de chucho (Stingray Pie) is a popular dish is Eastern Venezuela.

It is also taken as a food item in Eastern India by preparing its curry.

Stingray is also sometimes found in Australian and New Zealand cuisines.

While not independently valuable as a food source,[citation needed] the stingray's capacity to damage shell fishing grounds[44] can lead to bounties being placed on their removal.[citation needed]

Ecotourism

Stingrays are usually very docile and curious, their usual reaction being to flee any disturbance, but they sometimes brush their fins past any new object they encounter. Nevertheless, certain larger species may be more aggressive and should be approached with caution, as the stingray's defensive reflex (use of its venomous stinger) may result in serious injury or death.[45]

Other uses

The skin of the ray is used as an under layer for the cord or leather wrap (known as samegawa in Japanese) on Japanese swords due to its hard, rough, skin texture that keeps the braided wrap from sliding on the handle during use. They are also used to make exotic shoes, boots, belts, wallets, jackets, and cellphone cases.[citation needed]

Several ethnological sections in museums,[46] such as the British Museum, display arrowheads and spearheads made of stingray stingers, used in Micronesia and elsewhere.[47] Henry de Monfreid stated in his books that before World War II, in the Horn of Africa, whips were made from the tails of big stingrays, and these devices inflicted cruel cuts, so in Aden, the British forbade their use on women and slaves. In former Spanish colonies, a stingray is called raya látigo ("whip ray").

Fossils

Batoids (rays) belong to the ancient lineage of cartilaginous fishes. Fossil denticles (tooth-like scales in the skin) resembling those of today's chondrichthyans date at least as far back as the Ordovician, with the oldest unambiguous fossils of cartilaginous fish dating from the middle Devonian. A clade within this diverse family, the Neoselachii, emerged by the Triassic, with the best-understood neoselachian fossils dating from the Jurassic. The clade is represented today by sharks, sawfish, rays and skates.[48]

Although stingray teeth are rare on sea bottoms compared to the similar shark teeth, scuba divers searching for the latter do encounter the teeth of stingrays. Permineralized stingray teeth have been found in sedimentary deposits around the world, including fossiliferous outcrops in Morocco.[49]

Gallery

-

Spotted eagle rays are widespread along Atlantic coasts

-

Bull rays are found along European and African coasts

-

Bat rays are found around the Galápagos Islands and along the US west coast

-

Ocellate river stingrays are found in South American rivers

-

Diver interacting with a short-tail stingray

-

Leopard whiprays are vulnerable from overfishing

See also

References

- ^ a b Nelson JS (2006). Fishes of the World (fourth ed.). John Wiley. pp. 76–82. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- ^ Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE (1997). The Diversity of Fishes. Blackwell Science. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-86542-256-8.

- ^ Bester C, Mollett HF, Bourdon J (2017-05-09). "Pelagic Stingray". Florida Museum of Natural History, Ichthyology department.

- ^ The Future of Sharks: A Review of Action and Inaction CITES AC25 Inf. 6, 2011.

- ^ "IUCN Red List". International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014.

- ^ Carrier, Jeffrey C.; Musick, John A.; Heithaus, Michael R. (2012-04-09). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781439839263.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Khanna, D. R. (2004). Biology Of Fishes. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 9788171419081.

- ^ Kolmann, M. A.; Crofts, S. B.; Dean, M. N.; Summers, A. P.; Lovejoy, N. R. (13 November 2015). "Morphology does not predict performance: jaw curvature and prey crushing in durophagous stingrays". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (24): 3941–3949. doi:10.1242/jeb.127340. PMID 26567348.

- ^ Kajiura, null; Tricas, null (1996). "Seasonal dynamics of dental sexual dimorphism in the Atlantic stingray Dasyatis sabina". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 199 (Pt 10): 2297–2306. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 9320215.

- ^ "Stingray". bioweb.uwlax.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ Kardong, Kenneth (2015). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. 2 Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10121: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-07-802302-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Bedore CN, Harris LL, Kajiura SM (April 2014). "Behavioral responses of batoid elasmobranchs to prey-simulating electric fields are correlated to peripheral sensory morphology and ecology". Zoology. 117 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2013.09.002. PMID 24290363.

- ^ Stingray City – Altering Stingray Behavior & Physiology?. Divephotoguide.com (2009-04-14). Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ Tricas TC, Michael SW, Sisneros JA (December 1995). "Electrosensory optimization to conspecific phasic signals for mating". Neuroscience Letters. 202 (1–2): 129–32. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(95)12230-3. PMID 8787848. S2CID 42318841.

- ^ FAQs on Freshwater Stingray Behavior. Wetwebmedia.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). "Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958.

- ^ Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). "Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958.

- ^ Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). "Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958.

- ^ Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). "Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958.

- ^ Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). "Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958.

- ^ Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Atlantic Stingray. Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ Seubert, Curtis (April 24, 2017). "How Do Stingrays Take Care of Their Young?".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Stingrays born in female only tank". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2011-08-10.

- ^ Wang, Y (2015). "Design and Experiment on Biometic Robotic Fish Inspired by Freshwater Stingray". Journal of Bionic Engineering. 12 (2): 204–216. doi:10.1016/S1672-6529(14)60113-X. S2CID 136537698.

- ^ Macesic, J (2013). "Synchronized swimming: coordination of pelvic and pectoral fins during augmented punting by freshwater stingray Potamotrygon orbignyi". Zoology. 116 (3): 144–150. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2012.11.002. PMID 23477972.

- ^ a b c Fontanella J (2013). "Two- and three-dimensional geometries of batoids in relation to locomotor mode". Journal of Experimental Biology and Ecology. 446: 273–281. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2013.05.016.

- ^ Bottom II, R (2016). "Hydrodynamics of swimming in stingrays: numerical simulations and the role of the leading-edge vortex" (PDF). Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 788: 407–443. doi:10.1017/jfm.2015.702. S2CID 124395779.

- ^ Kolmann MA, Huber DR, Motta PJ, Grubbs RD (September 2015). "Feeding biomechanics of the cownose ray, Rhinoptera bonasus, over ontogeny". Journal of Anatomy. 227 (3): 341–51. doi:10.1111/joa.12342. PMC 4560568. PMID 26183820.

- ^ Dean MN, Bizzarro JJ, Summers AP (July 2007). "The evolution of cranial design, diet, and feeding mechanisms in batoid fishes". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1093/icb/icm034. PMID 21672821.

- ^ Curio, Eberhard (1976). The Ethology of Predation - Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81028-2. ISBN 978-3-642-81030-5. S2CID 8090692.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Wilga CD, Maia A, Nauwelaerts S, Lauder GV (February 2012). "Prey handling using whole-body fluid dynamics in batoids". Zoology. 115 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2011.09.002. PMID 22244456.

- ^ Kolmann MA, Welch KC, Summers AP, Lovejoy NR (September 2016). "Always chew your food: freshwater stingrays use mastication to process tough insect prey". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 283 (1838): 20161392. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1392. PMC 5031661. PMID 27629029.

- ^ Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, Giuseppe; Hillyer, Elizabeth V. (1989-01-01). "Mobulid Rays off Eastern Venezuela (Chondrichthyes, Mobulidae)". Copeia. 1989 (3): 607–614. doi:10.2307/1445487. JSTOR 1445487.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM, Lambie BS, Schep LJ (February 2009). "New Zealand's venomous creatures". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 122 (1290): 83–97. PMID 19319171. Archived from the original on April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Stingray Injury Case Reports". Clinical Toxicology Resources. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Flint DJ, Sugrue WJ (April 1999). "Stingray injuries: a lesson in debridement". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 112 (1086): 137–8. PMID 10340692.

- ^ "I thought stingrays were harmless, so how did one manage to kill the "Crocodile Hunter?"". 2006-09-11.

- ^ Discovery Channel Mourns the Death of Steve Irwin. animal.discovery.com

- ^ da Silva NJ, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, Aird SD (June 2015). "A Severe Accident Caused by an Ocellate River Stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in Central Brazil: How Well Do We Really Understand Stingray Venom Chemistry, Envenomation, and Therapeutics?". Toxins. 7 (6): 2272–88. doi:10.3390/toxins7062272. PMC 4488702. PMID 26094699.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, Marques EE, Soares AB, Quesniaux VF, Ryffel B, Lopes-Ferreira M, Lima C (August 2017). "Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 7912. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08395-y. PMC 5554156. PMID 28801624.

- ^ a b Pedroso CM, Jared C, Charvet-Almeida P, Almeida MP, Garrone Neto D, Lira MS, Haddad V, Barbaro KC, Antoniazzi MM (October 2007). "Morphological characterization of the venom secretory epidermal cells in the stinger of marine and freshwater stingrays". Toxicon. 50 (5): 688–97. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.06.004. PMID 17659760.

- ^ Enzor LA, Wilborn RE, Bennett WA (December 2011). "Toxicity and metabolic costs of the Atlantic stingray (Dasyatis sabina) venom delivery system in relation to its role in life history". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 409 (1–2): 235–239. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2011.08.026.

- ^ The Delicious and Deadly Stingray. Nyonya. New York, NY. (Partially from the Archives.). Deep End Dining (2006-09-05). Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ Weinheimer, Monica. "Dasyatidae Stingrays". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Sullivan BN (May 2009). "Stingrays: Dangerous or Not?". The Right Blue. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ FLMNH Ichthyology Department: Daisy Stingray. Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 17 July 2012.

- ^ Dasyatis rudis (Smalltooth Stingray). Iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 17 July 2012.

- ^ http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/vertebrates/basalfish/chondrofr.html UCMP Berkeley "Chondrichthyes: Fossil Record"

- ^ Heliobatis radians Stingray Fossil from Green River. Fossilmall.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

Bibliography

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Dasyatidae". FishBase. August 2005 version.

External links

- Life In The Fast Lane: Toxicology Conundrum #012

- "Beware the Ugly Sting Ray." Popular Science, July 1954, pp. 117–118/pp. 224–228.