Stimulus (economics)

In economics, stimulus refers to attempts to use monetary or fiscal policy (or stabilization policy in general) to stimulate the economy. Stimulus can also refer to monetary policies like lowering interest rates and quantitative easing.[1]

A stimulus is sometimes colloquially referred to as "priming the pump" or "pump priming",[2]

Concept

Often, the underlying assumption is that, due to a recession, production and employment are far below their sustainable potential (see NAIRU) due to lack of demand. It is hoped that this will be corrected by increasing demand and that any adverse side effects from stimulus will be mild.

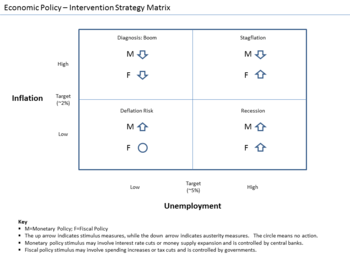

Fiscal stimulus refers to increasing government consumption or transfers or lowering taxes. Effectively this means increasing the rate of growth of public debt, except that particularly Keynesians often assume that the stimulus will cause sufficient economic growth to fill that gap partially or completely. See multiplier (economics).

Monetary stimulus refers to lowering interest rates, quantitative easing, or other ways of increasing the amount of money or credit.

Economist views

Milton Friedman argued that the Great Depression was caused by the fact that the Federal Reserve did not counteract the sudden reduction of money stock and velocity. Ben Bernanke argued, instead, that the problem was lack of credit, not lack of money, and hence, during the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve led by Bernanke provided additional credit, not additional liquidity (money), to stimulate the economy back on course. Jeff Hummel has analyzed[3] the different implications of these two conflicting explanations. President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Jeffrey Lacker, with Renee Haltom, has criticized[4] Bernanke's solution because "it encourages excessive risk-taking and contributes to financial instability." [5] Thomas Humphrey and Richard Timberlake concentrated in their book "Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder 1922-1938" on the real bills doctrine as a causative factor in the Great Depression.[6]

It is often argued that fiscal stimulus typically increases inflation, and hence must be counteracted by a typical central bank. Hence only monetary stimulus could work. Counter-arguments say that if the output gap is high enough, the risk of inflation is low, or that in depressions inflation is too low but central banks are not able to achieve the required inflation rate without fiscal stimulus by the government.

Monetary stimulus is often considered more neutral: decreasing interest rates make additional investments profitable, but yet only the most additional investments, whereas fiscal stimulus where the government decides the investments may lead to populism or corruption. On the other hand, the government can also take externalities into account, such as how new roads or railways benefit users that do not pay for them, and choose investments that are even more beneficial although not profitable.

Typically Keynesians are particularly strongly pro-stimulus, Austrians and Rational expectations economists against, and mainstream economists between the two.

History

This section needs expansion with: Information is US-centric, and also very limited. You can help by adding to it. (February 2021) |

In the 1930s, President Herbert Hoover was accused of "pump priming",[7] and President Franklin D. Roosevelt used the term favorably.[8] On March 26, 2020, the United States Senate passed a $2 trillion stimulus package in response to the COVID-19 pandemic with President Donald Trump's support.[9]

See also

References

- ^ "Economic Stimulus". Investopedia.

- ^ "Pump Priming". Investopedia.

- ^ Jeffrey Rogers Hummel (October 15, 2010). "BEN BERNANKE VERSUS MILTON FRIEDMAN: The Federal Reserve's Emergence as the U.S. Economy's Central Planner" (PDF).

- ^ Renee Haltom and Jeff rey M. Lacker (July 2014). "Should the Fed Do Emergency Lending?" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

- ^ Bernanke v. Friedman, professor Alex Tabarrok, July 15, 2014.

- ^ Humphrey, Thomas M.; Timberlake, Richard H. (2019). Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed : sources of monetary disorder 1922-1938. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute. ISBN 978-1-948647-12-0.

- ^ Horwitz, Steven (29 September 2011). "Herbert Hoover: Father of the New Deal" (PDF). Cato Institute. p. 5.

Hoover and his secretary of the treasury, Andrew Mellon (himself often wrongly portrayed as a defender of laissez faire), proposed $400 million in new federal buildings as well as $175 million in public works through the federal Shipping Board. These proposals met with approval from the professoriate as examples of 'constructive industrial statesmanship.' They were also ridiculed as 'pump priming' in a New York Tribune editorial cartoon of April 8, 1930...

- ^ Mead, Walter Russel (April 1998). "Signs of the Times: Deflation Ahead". Mother Jones.

- ^ Raju, Manu; Foran, Clare; Barrett, Ted; Wilson, Kristin (25 March 2020). "Why stimulus matters". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 25 March 2020.