Uterine inversion

| Uterine inversion | |

|---|---|

| |

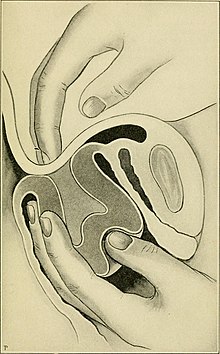

| Complete inverted uterus | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Symptoms | Postpartum bleeding, abdominal pain, mass in the vagina, low blood pressure[1] |

| Types | First, second, third, fourth degree[1] |

| Risk factors | Pulling on the umbilical cord or pushing on the top of the uterus before the placenta has detached, uterine atony, placenta previa, connective tissue disorders[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Seeing the inside of the uterus in the vagina[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Uterine fibroid, uterine atony, bleeding disorder, retained placenta[1] |

| Treatment | Standard resuscitation, rapidly replacing the uterus[1] |

| Medication | Oxytocin, antibiotics[1] |

| Prognosis | ~15% risk of death[3] |

| Frequency | About 1 in 6,000 deliveries[1][4] |

Uterine inversion is when the uterus turns inside out, usually following childbirth.[1] Symptoms include postpartum bleeding, abdominal pain, a mass in the vagina, and low blood pressure.[1] Rarely inversion may occur not in association with pregnancy.[5]

Risk factors include pulling on the umbilical cord or pushing on the top of the uterus before the placenta has detached.[1] Other risk factors include uterine atony, placenta previa, and connective tissue disorders.[1] Diagnosis is by seeing the inside of the uterus either in or coming out of the vagina.[2][6]

Treatment involves standard resuscitation together with replacing the uterus as rapidly as possible.[1] If efforts at manual replacement are not successful surgery is required.[1] After the uterus is replaced oxytocin and antibiotics are typically recommended.[1] The placenta can then be removed if it is still attached.[1]

Uterine inversion occurs in about 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 10,000 deliveries.[1][4] Rates are higher in the developing world.[1] The risk of death of the mother is about 15% while historically it has been as high as 80%.[3][1] The condition has been described since at least 300 BC by Hippocrates.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Uterine inversion is often associated with significant postpartum bleeding. Traditionally it was thought that it presented with haemodynamic shock "out of proportion" with blood loss, however blood loss has often been underestimated. The parasympathetic effect of traction on the uterine ligaments may cause bradycardia.

Causes

The most common cause is the mismanagement of 3rd stage of labor, such as:

- Fundal pressure

- Excess cord traction during the 3rd stage of labor

Other natural causes can be:

- Uterine weakness, congenital or not

- Precipitate delivery

- Short umbilical cord

It is more common in multiple gestation than in singleton pregnancies.

Associations

- Placenta praevia

- Fundal Placental Implantation

- Use of Magnesium Sulfate

- Vigorous fundal pressure

- Repeated cord traction

- short umbilical cord

Types

Treatment

Treatment involves standard resuscitation together with replacing the uterus as rapidly as possible.[1] If efforts at manual replacement are not successful surgery is required.[1] After the uterus is replaced oxytocin and antibiotics are typically recommended.[1] The placenta can then be removed if it is still attached.[1]

Epidemiology

Uterine inversion occurs in about 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 10,000 deliveries.[1][4] Rates are higher in the developing world.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Bhalla, Rita; Wuntakal, Rekha; Odejinmi, Funlayo; Khan, Rehan U (January 2009). "Acute inversion of the uterus". The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 11 (1): 13–18. doi:10.1576/toag.11.1.13.27463.

- ^ a b Mirza, FG; Gaddipati, S (April 2009). "Obstetric emergencies". Seminars in Perinatology. 33 (2): 97–103. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2009.01.003. PMID 19324238.

- ^ a b Gandhi, Alpesh; Malhotra, Narendra; Malhotra, Jaideep; Gupta, Nidhi; Bora, Neharika Malhotra (2016). Principles of Critical Care in Obstetrics. Springer. p. 335. ISBN 9788132226925.

- ^ a b c Andersen, H. Frank; Hopkins, Michael P. (2009). "Postpartum Hemorrhage". The Global Library of Women's Medicine. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10138.

- ^ Mehra, R; Siwatch, S; Arora, S; Kundu, R (12 December 2013). "Non-puerperal uterine inversion caused by malignant mixed mullerian sarcoma". BMJ Case Reports. 2013: bcr2013200578. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200578. PMC 3863018. PMID 24334469.

- ^ Apuzzio, Joseph J.; Vintzileos, Anthony M.; Berghella, Vincenzo; Alvarez-Perez, Jesus R. (2017). Operative Obstetrics, 4E. CRC Press. p. PT822. ISBN 9781498720588.

- ^ Uterine inversion Archived 2009-10-04 at the Wayback Machine - Better Health Channel; State of Victoria, Australia; accessed 2009-04-03