Foreign policy of Charles de Gaulle

The Foreign policy of Charles de Gaulle covers the diplomacy of Charles de Gaulle as French leader 1940–46 and 1958–1969, along with his followers.

Status of France 1940-44

Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his top aides Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, and Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Alan Brooke in 1940-41 moved quickly to establish a base for de Gaulle in London.[1] Control of the overseas French Empire was seen as the central issue, In the British government was prepared to use military support to help de Gaulle regain control. De Gaulle set up a shadow government, including a French National Council and a Resistance movement inside both Vichy France and German-controlled France.[2] To establish his own leadership over like-minded Frenchmen, de Gaulle began broadcasting to France using BBC facilities.[3] De Gaulle was especially keen to set up a Resistance movement inside France,[4] However, many top British officials, as well as Roosevelt and sometimes even Churchill, still hoped for an understanding with Vichy France under Philippe Pétain. De Gaulle was totally opposed to any such relationship. Friction with Churchill's government continued to the end of 1942, centering around plans for the Anglo-American invasion of North Africa.[5] On that matter the United States played the dominant role. Roosevelt continued to recognize the Vichy government, with Ambassador William D. Leahy in residence in Vichy. The embassy was finally closed when Germany seized control of Vichy France in late 1942.[6][7]

In June 1941, British and Free French troops invaded Syria, then part of the Vichy overseas empire and used as a base by Nazi elements.[8] Churchill decided to give Syria independence as a gesture to mollify Arab nationalism. De Gaulle strongly objected as he needed it for his base of operations in the Middle East. At one point Churchill was ready 108 to 11 to remove de Gaulle as head of the Free French. De Gaulle had no choice except to acquiesce to an independent Syria.[9][10][11]

The command situation in North Africa was especially complex, with Roosevelt preferring François Darlan, The senior Vichy official who happened to be in command for Algeria when the invasion took place. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied commander on the spot recognized Darlan as commander of all French forces in the area and recognized his self-nomination as High Commissioner of France (head of civil government) for North and West Africa on 14 November. In return, on 10 November, Darlan ordered all French forces to join the Allies.[dubious – discuss] His order was obeyed; not only in French North Africa, but also by the Vichy forces in French West Africa with its potentially useful facilities at Dakar.[12] After Darlan was assassinated in December 1942, Roosevelt preferred General Henri Giraud. Roosevelt had met with de Gaulle in Washington, but never hid his distrust and distaste. De Gaulle In turn never forgave the Americans for this humiliation.[13]

Postwar planning

De Gaulle and the Free French were largely excluded from the postwar planning by Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin, and ignored by the U.S. State Department. It was humiliating for de Gaulle. The Americans and to a lesser extent the British distrusted de Gaulle's usefulness and leadership of France. De Gaulle was not invited to summit meetings at Tehran, Yalta or Potsdam. At the Casablanca Conference on 24 January 1943, Giraud was present but de Gaulle at first refused but then accepted an invitation. Roosevelt and Churchill between themselves drafted an agreement on how liberated France would be governed. They agreed on a merger between Giraud's Algiers Imperial Council and de Gaulle's London-based French National Committee. However Roosevelt's original draft called for General Giraud to be in charge. Churchill secured major changes that gave responsibility to the French National Committee under de Gaulle.[14][15] In 1945 France was given one of the five seats on the UN Security Council, with a veto, as well as a zone of Germany. Nevertheless it was kept from actually taking a leadership role regarding the UN or Germany.[16] The French were angry at not being invited to Potsdam, but they did fairly well in the end.[17]

Algeria 1958

The May 1958 seizure of power in Algiers by French army units and French settlers opposed to concessions in the face of Arab nationalist insurrection ripped apart the unstable Fourth Republic. The National Assembly brought him back to power during the May 1958 crisis. De Gaulle founded the Fifth Republic with a strengthened presidency, and he was elected in the latter role. He managed to keep France together while taking steps to end the war, much to the anger of the Pieds-Noirs (Frenchmen settled in Algeria) and the military; both previously had supported his return to power to maintain colonial rule. He granted independence to Algeria in 1962 and progressively to other French colonies.[18]

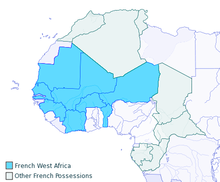

French West Africa

French conservatives were disillusioned with the colonial experience after the disasters in Indochina and Algeria. They wanted to cut all ties to the numerous colonies in French Sub-Saharan Africa. During the war, de Gaulle had successfully based his Free France movement and the African colonies. After a visit in 1958, he made a commitment to make sub-Saharan French Africa a major component of his foreign-policy.[19] All the colonies in 1958, except Guinea, voted to remain in the French Community, with representation in Parliament and a guarantee of French aid. In practice, nearly all the colonies became independent in the late 1950s, but maintained very strong connections.[20] Under close supervision from the president, French advisors played a major role in civil and military affairs, thwarted coups, and, occasionally, replaced upstart local leaders. The French colonial system had always been based primarily on local leadership, in sharp contrast to the situation in British colonies. The French colonial goal had been to assimilate the natives into mainstream French culture, with a strong emphasis on the French language. From de Gaulle's point of view, close association gave legitimacy to his visions of global client grandeur, certified his humanitarian credentials, provided access to oil, uranium and other minerals, and provided a small but steady market for French manufacturers. Above all it guaranteed the vitality of French language and culture in a large slice of the world that was rapidly growing in population. De Gaulle's successors Georges Pompidou (1969–74) and Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1974-1981) continued de Gaulle's African policy. It was supported with French military units, and a large naval presence in the Indian Ocean. Over 260,000 Frenchmen worked in Africa, focused especially on delivering oil supplies. There was some effort to build up oil refineries and aluminum smelters, but little effort to develop small-scale local industry, which the French wanted to monopolize for the mainland. Senegal, Ivory Coast, Gabon, and Cameroon were the largest and most reliable African allies, and received most of the investments.[21] During the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), France supported breakaway Biafra, but only on a limited scale, providing mercenaries and obsolete weaponry. De Gaulle's goals were to protect its nearby ex-colonies from Nigeria, to stop Soviet advances, and to acquire a foothold in the oil-rich Niger delta.[22]

Politics of Grandeur

Proclaiming that grandeur was the essential to the nature of France, de Gaulle initiated his "Politics of Grandeur".[23] He demanded complete autonomy for France in world affairs, which meant that it has its major decisions which could not be forced upon it by NATO, the European Community or anyone else. De Gaulle pursued a policy of "national independence." He twice vetoed Britain's entry into the Common Market, fearing it might overshadow France in European affairs.[24][25] While not officially abandoning NATO, he withdraw from its military integrated command, fearing that the United States had too much control over NATO.[26] He launched an independent nuclear development program that made France the fourth nuclear power.[27]

Hostility to Anglo-Saxons

He restored cordial Franco-German relations in order to create a European counterweight between the "Anglo-Saxon" (American and British) and Soviet spheres of influence. De Gaulle openly criticised the U.S. intervention in Vietnam.[28] He was angry at American economic power, especially what his Finance minister called the "exorbitant privilege" of the U.S. dollar.[29] He went to Canada and proclaimed "Vive le Québec libre", The catchphrase for an independent Quebec.[30]

Partial withdrawal from NATO in 1966

De Gaulle's vision called for a strong, independent France, armed with nuclear weapons, expecting that his vigor and weapons would enable Paris to deal with Washington on equal terms. Europe should emancipate itself from America and become a third force in the Cold War where it could rally neutral nations and perhaps reach a détente with the Soviet Union. NATO stood in the way of these goals. De Gaulle protested at the strong role of the United States in NATO. He considered the "special relationship" between the U.S. and the UK to be too close and too detrimental to the French role in Europe. The existing NATO situation gave the United States veto power on nuclear weapons and thus prevented France from having a fully independent nuclear force of its own. In a memorandum sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan on 17 September 1958, he proposed a tripartite directorate that would put France on an equal footing with them. He also wanted NATO's coverage to expand to include French Algeria, where France was waging a counter-insurgency and sought NATO assistance.[31] De Gaulle's ideas went nowhere, so he began the development of an Force de dissuasion (an independent French nuclear force). He refused to sign the 1963 agreement against underground nuclear testing. In 1963 he vetoed Britain's entry into the EEC (the European Union). No NATO countries followed his lead. In July 1964, de Gaulle presented West Germany with a clear choice: "Either you [West Germany] follow a policy subordinated to the US or you adopt a policy that is European and independent of the U.S., but not hostile to them."[32] West Germany rejected de Gaulle's ultimatum by pledging total loyalty to the U.S. ending his plan for leadership of Europe. In 1966-67 he withdrew France from NATO's military structure—which required an American to be in command of any NATO military action. He expelled NATO's headquarters and NATO units from French soil.[33][34] The 15 NATO partners did not ignore De Gaulle's threats. Instead they worked to more closely cooperate with one to neutralize his countermeasures.[35]

France officially remained a NATO member and finally in 2009 President Nicolas Sarkozy ended France's estrangement from NATO, closing the Gaullist chapter. James Ellison explains why Western Europe rejected de Gaulle's vision:

- he antagonised his allies in the EEC [European Community] and in the Atlantic Alliance and he worked against the prevailing political atmosphere in the West. That atmosphere ....was a general belief in interdependence and integration and their achievement through a reformed NATO and Atlantic Alliance and an advancing EEC. During the second half of the 1960s, independence and national sovereignty became outmoded and it was amid de Gaulle’s pursuit of them that this became clear.[36]

In de Gaulle's very long-term perspective, all that really mattered was the nation state, not ideologies that come and go such as communism. That is the good relationship of the French state and the Russian state had a higher priority than petty issues such as socialism and capitalism. Breaking through the polarization of the Cold War would allow France to assume a major leadership role in the world. The polarization was furthermore illegitimate, since France had been excluded from Yalta and the other episodes in which the Cold War had been established in 1945-47. By now, he was confident, there was no risk of a European war, and the Soviet Union had so many internal troubles that it was ready for détente. It had split bitterly with China and the two were now engaged in a global battle for control of local Communist movements. His diplomats opened informal discussions with Romania, Bulgaria and Poland. Moscow, however, was so alarmed at de Gaulle's suggestion that the Soviet satellites should show some independence of their own. When Czechoslovakia did show independence, Moscow and its client states invaded and crushed the new government there in 1968. Détente was dead as were de Gaulle's grandiose plans.[37]

Evaluations

French scholar Alfred Grosser has evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of de Gaulle's foreign policy. On the positive side, the highest praise goes to a restoration of French grandeur in rank in world affairs, a return to a historic ranking. The French themselves are especially pleased with this development. As Foreign Minister Maurice Couve de Murville told the National Assembly in 1964: France has resumed her position in all sectors of world affairs."[38] There is little dissent with this conclusion inside France, even from de Gaulle's old enemies. However, the rest of the world looks at the claim with some amusement, as de Gaulle has not restored the diplomatic reputation of Paris in Washington, London, or Moscow nor in Beijing, New Delhi, Tokyo, Bonn and Rome. West Germany remained much more closely aligned with the United States in major world affairs, especially regarding NATO. When Soviet control of Eastern Europe collapsed in 1989, the United States led the effort to reunite Germany, despite serious French doubts. Secondly, France did establish its independence of the Anglo-Saxon powers – especially the United States, and also Great Britain. De Gaulle's anti-American rhetoric did indeed rub Americans the wrong way, and give some encouragement to intellectuals hostile to Americanism.[39][40] His pulling the French military out of NATO was basically a symbolic action, with few practical results.[41] It did mean that NATO headquarters was relocated to Belgium, with the result that French generals gave up their voice in NATO policy. Most historians conclude that NATO grew stronger, and de Gaulle had failed to weaken it or lessen American dominance.[42]

As long as de Gaulle was in power, he successfully blocked British entry into the European Union. When he retired, so too was that exclusionary policy. Grosser concludes that the enormous French effort to become independent of Washington in nuclear policy by building its own "force de frappe" has been a failure. The high budget cost came at the expense of weakening France's conventional military capabilities. Neither Washington nor Moscow pays much attention to the French nuclear deterrent one way or another. As a neutral force in world affairs, France does have considerable influence over its former colonies, much more than any other ex-colonial power. But the countries involved are not powerhouses, and the major neutral nations at the time, such as India, Yugoslavia and Indonesia, paid little attention to Paris.[43] He did not have a major influence at the United Nations.[44] While the French people supported and admired the foreign policy of Charles de Gaulle at the time and in retrospect, he made it all himself with scant regard to French public or elite opinion.[45][46]

See also

Notes

- ^ Jonathan Fenby, The General: Charles De Gaulle and the France He Saved (2010) pp 30-38.

- ^ Fenby, The General (2010) pp 204-218.

- ^ Kay Chadwick, "Our enemy's enemy: Selling Britain to occupied France on the BBC French Service." Media History 21.4 (2015): 426-442. Online

- ^ Jonathan Fenby, The General: Charles De Gaulle and the France He Saved (2010) pp 169-175.

- ^ Sir Llewellyn Woodward, British Foreign Policy in the Second World War (1962) pp 91-123.

- ^ William L. Langer, Our Vichy gamble (1947).

- ^ Simon Berthon, Allies at War: The Bitter Rivalry among Churchill, Roosevelt & de Gaulle (2001) pp 87-101.

- ^ Simon Berthon, Allies at War: The Bitter Rivalry among Churchill, Roosevelt & de Gaulle (2001) pp 87-101.

- ^ Martin Mickelsen, Martin. "Another Fashoda: The Anglo-Free French Conflict over the Levant, May–September, 1941." Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire 63.230 (1976): 75-100 online.

- ^ Woodward, British Foreign Policy in the Second World War (1962) pp 108-111.

- ^ Meir Zamir, "De Gaulle and the Question of Syria and Lebanon during the Second World War: Part I." Middle Eastern Studies 43.5 (2007): 675-708.

- ^ Arthur L. Funk, "Negotiating the'Deal with Darlan'." Journal of Contemporary History 8.2 (1973): 81-117. online

- ^ Jean Lacouture, De Gaulle: The Rebel, 1890-1944 (1990) 1:332-351.

- ^ Fenby, The General, pp 195-201.

- ^ Arthur Layton Funk, "The 'Anfa Memorandum': An Incident of the Casablanca Conference." Journal of Modern History 26.3 (1954): 246-254. online

- ^ Andrew Williams, "France and the Origins of the United Nations, 1944–1945: 'Si La France ne compte plus, qu’on nous le dise'." Diplomacy & Statecraft 28.2 (2017): 215-234.

- ^ Julian Jackson, Charles de Gaulle (2003) p 39.

- ^ Winock, Michel. "De Gaulle and the Algerian Crisis 1958-1962." in Hugh Gough and John Home, eds., De Gaulle and Twentieth Century France (1994) pp 71-82.

- ^ Julian Jackson, De Gaulle (2018), pp 490-93, 525, 609-615.

- ^ Patrick Manning, Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880–1995 (1999) pp 137-41, 149-50, 158-62.

- ^ John R. Frears, France in the Giscard Presidency (1981) pp 109-127.

- ^ Christopher Griffin, "French military policy in the Nigerian Civil War, 1967–1970." Small Wars & Insurgencies 26.1 (2015): 114-135.

- ^ Kolodziej, Edward A (1974). French International Policy under de Gaulle and Pompidou: The Politics of Grandeur. p. 618.

- ^ Helen Parr, "Saving the Community: The French Response to Britain's Second EEC Application in 1967", Cold War History (2006) 6#4 pp 425–454

- ^ W. W. Kulski (1966). De Gaulle and the World: The Foreign Policy of the Fifth French Republic. Syracuse UP. p. 239ff.

- ^ Kulski (1966). De Gaulle and the World: The Foreign Policy of the Fifth French Republic. p. 176.

- ^ Gabrielle Hecht and Michel Callon, ed. (2009). The Radiance of France: Nuclear Power and National Identity after World War II. MIT Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9780262266178.

- ^ "De Gaulle urges the United States to get out of Vietnam". History.com. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Barry Eichengreen (2011). Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. Oxford UP. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-978148-5.

- ^ See Wayne C. Thompson, Canada 2014 (2013)

- ^ Anand Menon, France, NATO, and the limits of independence, 1981–97 (2000) p 11.

- ^ Garret Joseph Martin (2013). General de Gaulle's Cold War: Challenging American Hegemony, 1963-68. p. 35. ISBN 9781782380160.

- ^ Christian Nuenlist; Anna Locher; Garret Martin (2010). Globalizing de Gaulle: International Perspectives on French Foreign Policies, 1958–1969. Lexington Books. pp. 99–102. ISBN 9780739142509.

- ^ Garret Martin, "The 1967 withdrawal from NATO–a cornerstone of de Gaulle's grand strategy?." Journal of Transatlantic Studies 9.3 (2011): 232-243.

- ^ Christian Nuenlist, "Dealing with the devil: NATO and Gaullist France, 1958–66." Journal of Transatlantic Studies 9.3 (2011): 220-231.

- ^ James Ellison, "Separated by the Atlantic: the British and de Gaulle, 1958–1967" in Glyn Stone and Thomas G. Otte, ed. (2013). Anglo-French Relations since the Late Eighteenth Century. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 9781317997832.

- ^ Martin, "The 1967 withdrawal from NATO–a cornerstone of de Gaulle's grand strategy?." pp. 238-243.

- ^ Alfred Grosser, French foreign policy under De Gaulle (1967) p 129.

- ^ Kulski, pp 77–79.

- ^ James Chace and Elizabeth Malkin, ‘The Mischief-Maker: The American Media and De Gaulle, 1964–1968’, in Robert O. Paxton and Nicholas Wahl, eds., De Gaulle and the United States (1994), 359–76.

- ^ Gale A. Mattox; Stephen M. Grenier (2015). Coalition Challenges in Afghanistan: The Politics of Alliance. p. 124. ISBN 9780804796293.

- ^ Garret Joseph Martin (2013). General de Gaulle's Cold War: Challenging American Hegemony, 1963-68. p. 170. ISBN 9781782380160.

- ^ Kulski, pp 314–320.

- ^ Kulski, pp 321–389.

- ^ Grosser, French foreign policy under De Gaulle (1967) pp 128–144.

- ^ Kulski, pp 37–38.

Further reading

- Argyle, Ray. The Paris Game: Charles de Gaulle, the Liberation of Paris, and the Gamble that Won France (Dundurn, 2014) online review

- Bell, P. M. H. France and Britain, 1940-1994: The Long Separation (Longman, 1997) 320 pp.

- Berstein, Serge, and Peter Morris. The Republic of de Gaulle 1958–1969 (2006) excerpt and text search

- Berthon, Simon. Allies at War: The Bitter Rivalry among Churchill, Roosevelt, and de Gaulle. (2001). 356 pp. online

- Bosher, J. F. The Gaullist Attack on Canada, 1967-1997 (1999)

- Bozo, Frédéric. Two Strategies for Europe: De Gaulle, the United States and the Atlantic Alliance (2000)

- Cameron, David R. and Hofferbert, Richard I. "Continuity and Change in Gaullism: the General's Legacy." American Journal of Political Science 1973 17(1): 77–98. ISSN 0092-5853, a statistical analysis of the Gaullist voting coalition in elections 1958–73 Fulltext: Abstract in Jstor

- Cerny, Philip G. The Politics of Grandeur: Ideological Aspects of de Gaulle's Foreign Policy. (1980). 319 pp.

- Chassaigne, Philippe, and Michael Dockrill, eds. Anglo-French Relations, 1898-1998: From Fashoda to Jospin (2002) online

- Cogan, Charles G. Forced to Choose: France, the Atlantic Alliance, and NATO--Then and Now (1997)

- Cogan, Charles G. Oldest Allies, Guarded Friends: The United States and France since 1940 (1994)

- Costigliola, Frank. France and the United States: The Cold Alliance since World War II (1992)

- DePorte, Anton W. De Gaulle's foreign policy, 1944–1946 (1967).

- Diamond, Robert A. France under de Gaulle (Facts on File, 1970), highly detailed chronology 1958-1969. 319pp

- Facts on File. France under De Gaulle (1970), highly detailed summary of events

- Fenby, Jonathan. The General: Charles De Gaulle and the France He Saved (2011), popular biography online

- Friend, Julius W. The Linchpin: French-German Relations, 1950-1990 (1991)

- Gendron, Robin S. "The two faces of Charles the Good: Charles de Gaulle, France, and decolonization in Quebec and New Caledonia." International Journal 69.1 (2014): 94-109.

- Gordon, Philip H. A Certain Idea of France: French Security Policy and the Gaullist Legacy (1993)

- Gough, Hugh, ed. De Gaulle and twentieth-century France (1997) online

- Grosser, Alfred. French foreign policy under De Gaulle (1977)

- Hitchcock, William I. France Restored: Cold War Diplomacy and the Quest for Leadership in Europe, 1944-1954 (1998)

- Hoffmann, Stanley. Decline or Renewal? France since the 1930s (1974)

- Ionescu, Ghita. Leadership In An Interdependent World: The Statesmanship Of Adenauer, Degaulle, Thatcher, Reagan and Gorbachev (Routledge, 2019). online

- Jackson, Julian. Charles de Gaulle (2003), 172pp

- Jackson, Julian. A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle (2018) 887pp; the most recent major biography.

- Johnson, Douglas. "De Gaulle and France’s Role in the World." in Hugh Gough and John Horne, eds. De Gaulle and Twentieth Century France (1994): 83-94.

- Kersaudy, François. "Churchill and de Gaulle." in Douglas Johnson, Richard Mayne, Robert Tombs eds Cross Channel Currents: 100 Years of the Entente Cordiale Routledge, 2004. 134-139. online

- Kersaudy, Francois. Churchill and De Gaulle (2nd ed 1990) 482pp. online

- Kolodziej, Edward A. French International Policy under de Gaulle and Pompidou: The Politics of Grandeur (1974)

- Kulski, W. W. De Gaulle and the World: The Foreign Policy of the Fifth French Republic (1966) online free to borrow

- Lacouture, Jean. De Gaulle: The Ruler 1945–1970 (v 2 1993), 700 pp, a major scholarly biography. online

- Ledwidge, Bernard. De Gaulle (1982) pp 259–305.

- Logevall, Fredrik. "De Gaulle, Neutralization, and American Involvement in Vietnam, 1963–1964," The Pacific Historical Review Vol. 61, No. 1 (Feb. 1992), pp. 69–102 in JSTOR

- Mahan, E. Kennedy, De Gaulle and Western Europe. (2002). 229 pp.

- Mahoney, Daniel J. "A 'Man of Character': The Statesmanship of Charles de Gaulle," Polity (1994) 27#1 pp. 157–173 in JSTOR

- Mangold, Peter. The Almost Impossible Ally: Harold Macmillan and Charles de Gaulle. (2006). 275 pp. IB Tauris, London, ISBN 978-1-85043-800-7 online

- Martin, Garret. "The 1967 withdrawal from NATO–a cornerstone of de Gaulle's grand strategy?." Journal of Transatlantic Studies 9.3 (2011): 232-243.

- Newhouse, John. De Gaulle and the Anglo-Saxons (1970)

- Nuenlist, Christian et al. eds. Globalizing de Gaulle: International Perspectives on French Foreign Policies, 1958–1969 (2010).

- O'Dwyer, Graham. Charles de Gaulle, the International System, and the Existential Difference (Routledge, 2017).

- Paxton, Robert O. and Wahl, Nicholas, eds. De Gaulle and the United States: A Centennial Reassessment. (1994). 433 pp.

- Pinder, John. Europe against De Gaulle (1963)

- Pratt, Julius W. "De Gaulle and the United States: How the Rift Began," History Teacher (1968) 1#4 pp. 5–15 in JSTOR

- Tulli, Umberto. "Which democracy for the European Economic Community? Fernand Dehousse versus Charles de Gaulle." Parliaments, Estates and Representation 37.3 (2017): 301-317.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders. (2005). 292 pp. chapter on de Gaulle

- Werth, Alexander. The De Gaulle Revolution (1960)

- White, Dorothy Shipley. Black Africa and de Gaulle: From the French Empire to Independence. (1979). 314 pp.

- Williams, Andrew. "Charles de Gaulle: The Warrior as Statesman." Global Society 32.2 (2018): 162- [ online] 175+. excerpt

- Williams, Charles. The Last Great Frenchman: A Life of General De Gaulle (1997), 560pp. online

- Williams, Philip M. and Martin Harrison. De Gaulle's Republic (1965)

- Woodward, Sir Llewellyn. British Foreign Policy in the Second World War (1962).

- Young, John. Stalin and de Gaulle History Today (June 1990), Vol. 40 Issue 6, pp 20–26 in 1944-45 they both wanted to keep Germany weak and to defy US and UK.

Historiography

- Byrne, Jeffrey James, et al. Globalizing de Gaulle: International Perspectives on French Foreign Policies, 1958–1969 (Lexington Books, 2010).

- Hazareesingh, Sudhir. In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of de Gaulle (Oxford UP, 2012).

- Kuisel, Richard F. "American Historians in Search of France: Perceptions and Misperceptions." French Historical Studies 19.2 (1995): 307-319.

- Loth, Wilfried. "Explaining European integration: the contribution from historians." JEIH Journal of European Integration History 14.1 (2008): 9-27. online

- Moravcsik, Andrew. "Charles de Gaulle and Europe: the new revisionism." Journal of Cold War Studies 14.1 (2012): 53-77.