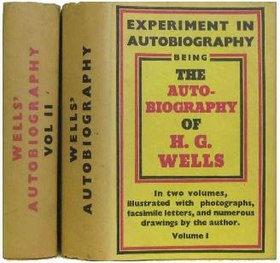

Experiment in Autobiography

First UK edition | |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Original title | Experiment in Autobiography: Discoveries and Conclusions of a Very Ordinary Brain (since 1866) |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Victor Gollancz Ltd |

Publication date | September 1934 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 840 (707 in Macmillan's 1934 one-volume US edition) |

| Preceded by | Stalin-Wells Talk New Statesman pamphlet (1934)] |

| Followed by | The New America: The New World |

Experiment in Autobiography is an autobiographical work by H.G. Wells, originally published in two volumes.[1] He began to write it in 1932, and completed it in the summer of 1934.

Experiment in Autobiography is divided into eight "chapters" (the last two of which are more than 100 pages long) which are divided in toto into 56 sections. Some sections are narrative, while others include long digressions into matters philosophical, political, sociological, or biographical.[2]

In the introductory section, Wells describes himself as a "mental worker" whose "thoughts and work are encumbered by claims and vexations and I cannot see any hope of release from them"; in the conclusion, he says that he has "[written] himself out of that mood of discontent" and is resolved to devote the rest of his life to the "faith and service of constructive world revolution."[3] "[I]n 1900 I had already grasped the inevitability of a World State and the complete insufficiency of the current parliamentary methods of democratic government," and Wells's devotion to "the great civilization of the future" is the dominant motif of the book.[4]

Wells emphasises his humble origins and the fortuitousness of his escape from the milieu in which he was born. Two broken legs were crucial. Wells's tibia was broken in an accident in 1874 when he was seven. During his weeks of recuperation he discovered the world of books.[5] Three years later his father broke his leg in a fall—another "cardinal stroke of good fortune," Wells thought, because it forced his mother into employment and, as a result, the young Wells became a resident apprentice, a placement against which he rebelled. Had his father not broken his leg, he wrote, "I have no doubt I should have followed in the footsteps of Frank and Freddy and gone on living at home under my mother's care, while I went daily to some shop, some draper's shop, to which I was bound apprentice. This would have seemed so natural and necessary that I should not have resisted."[6]

Wells presents his career as a writer as the result of another happenstance: in 1887, when he was teaching at the Holt Academy in Wrexham, Wales, one of his kidneys was crushed in a football injury. A few weeks later he was coughing up blood, and tuberculosis was (probably mistakenly) diagnosed. Wells had to give up his job. Later, back in London, a dramatic relapse forced him to abandon teaching altogether in 1893, and to devote himself instead to writing.

The work contains an abundant selection of the humorous sketches Wells called "picshuas" and produced mostly to amuse his second wife on an almost daily basis.

Posthumous Postscript

Experiment in Autobiography describes in some detail Wells's early sexual development,[7] his first marriage to his cousin Isabel Mary Wells, and the beginning of his second marriage to Amy Catherine Robbins (whom Wells and others called "Jane"), but omits discussion of the intimate life of his later years.

A posthumous volume of Wells's unpublished writings on the sexual aspect of his life, which he began to write in the fall of 1934 and regarded as a "Postscript" to Experiment in Autobiography, was published in 1984 by his son G.P. Wells as H.G. Wells in Love.[8][9]

This and other material inform David Lodge's novel about Wells, A Man of Parts (Viking Penguin, 2011).[10]

Reception

Experiment in Autobiography was well received by friends and reviewers, many of whom regarded the work as a masterpiece. It also earned the appreciation of some who were portrayed in it, like Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Sales, though, fell short of Wells's expectations.[11]

References

- ^ Biographer Michael Sherborne (H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life [Peter Owen, 2010], pp. 299–300) called Experiment in Autobiography "by far the best of [Wells's] later books," and biographer David C. Smith called it "[o]ne of the great autobiographies of this century" and "one of the best testaments to the human condition and its possibility" (H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal [Yale University Press, 1986], pp. 418–19).

- ^ These include remarkable estimates of Henry James, George Gissing, Joseph Conrad, Stephen Crane, Graham Wallas, George Bernard Shaw, and Arnold Bennett, among others.

- ^ H.G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1934), pp. 1 & 705.

- ^ H.G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1934), pp. 556–58.

- ^ H.G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1934), Ch. 2, §5, pp. 53–58.

- ^ H.G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1934), pp. 80–82.

- ^ Even mentioning "a very slight slant toward homosexuality," which is remarkable given the almost total silence on this theme in Wells's dozens of novels. H.G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (New York: Macmillan, 1934), p. 350.

- ^ "The secret loves of H.G. Wells unmasked". TheGuardian.com. 7 January 2001.

- ^ Huntington, John (1985). "H. G. Wells in Love: Postscript to an Experiment in Autobiography (Review)". MFS Modern Fiction Studies. 31 (4): 804–805. doi:10.1353/mfs.0.1132. S2CID 162337751.

- ^ "A Man of Parts by David Lodge – review". TheGuardian.com. 17 April 2011.

- ^ David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal (Yale University Press, 1986), pp. 418–21.

External links

- Experiment in Autobiography at Faded Page (Canada)