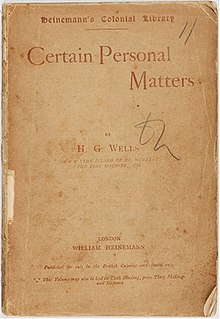

Certain Personal Matters

First edition | |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Original title | Certain Personal Matters: A Collection of Material, Mainly Autobiographical |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Essays |

| Publisher | William Heinemann |

Publication date | 1897 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

Certain Personal Matters is an 1897 collection of essays selected by H. G. Wells from among the many short essays and ephemeral pieces he had written since 1893.[1] The book consists of thirty-nine pieces ranging from about eight hundred[2] to two thousand words[3] in length. A one-shilling reprint (two shillings in cloth) was issued in 1901 by T. Fisher Unwin.

The essays in Certain Personal Matters are written from a consistent first-person perspective, but only one describes an identifiable event in Wells's life—how he responded to being diagnosed with tuberculosis in the fall of 1887.[4]

The other essays adopt the playful persona of an aspiring young writer living in modest circumstances with a wife, Euphemia, who is only sketchily and obliquely described. Their tone reflects the demands of the market in London magazines for "short essays, or short stories, often with a twist, which can be read in half a dozen minutes, but which will pique a reader's attention and ultimately allow him to think, 'How true. I have done that myself', or to make some similar remark."[5]

More than half of the essays are humorous social satire; serious subjects are addressed only ironically. Politics, historical and economic topics, and identifiable portraiture are eschewed. Ten essays have literary themes, and in these, too, the point of view is humorous. One ("On Schooling and the Phases of Mr. Sandsome") gently critiques the choice of subjects studied in the course of primary and secondary education. Half a dozen essays engage scientific themes, especially natural selection and evolution, and in "The Extinction of Man" Wells shows he is contemplating themes that would be expressed in his next novel, The War of the Worlds: "Even now, for all we can tell, the coming terror may be crouching for its spring and the fall of humanity may be at hand."

Composition and Publication

The essays in Certain Personal Matters rely on stock characters that Wells developed in his early days as a writer. This vein was inspired by his reading of When a Man's Single, an 1888 novel by J.M. Barrie, in which a character explains that saleable articles can be devised from everyday things like pipes, umbrellas, and flower pots.[6] According to biographer David C. Smith, one character is "probably based on his father (and perhaps partly on his older brothers), another based on his mother apparently (although the character is always referred to as an 'aunt', which may be somewhat symbolic), and a third character, 'Euphemia'. This last is usually thought to be a portrait of Jane [Catherine] Wells, though the figure may have some traits of Isabel [Wells's cousin and first wife] as well."[7]

"Wells naturally retained affection for the writings that had launched his career, so much so that he became embroiled in a furious dispute about the contents and title page with the publisher, who eventually had to call in Gissing to act as a mediator and persuade Wells to climb down."[8]

Certain Personal Matters was well received; one critic called it "a very pleasant moneysworth, full of wit and humour." The book sold well and was never remaindered.[9]

Contents

The essays are presented approximately chronologically rather than thematically:

- "Thoughts on Cheapness and My Aunt Charlotte"

- "The Trouble of Life"

- "On the Choice of a Wife"

- "The House of Di Sorno: A Manuscript Found in a Box"

- "Of Conversation: An Apology"

- "In a Literary Household"

- "On Schooling and the Phases of Mr. Sandsome"

- "The Poet and the Emporium"

- "The Language of Flowers"

- "The Literary Regimen"

- "House-Hunting as an Outdoor Amusement"

- "Of Blades and Bladery"

- "Of Cleverness: Apropos of One Crichton"

- "The Pose Novel"

- "The Veteran Cricketer"

- "Concerning a Certain Lady"

- "The Shopman"

- "The Book of Curses"

- "Dunstone's Dear Lady"

- "Euphemia's New Entertainment"

- "For Freedom of Spelling: The Discovery of an Art"

- "Incidental Thoughts on a Bald Head"

- "Of a Book Unwritten"

- "The Extinction of Man"

- "The Writing of Essays"

- "The Parkes Museum"

- "Bleak March in Epping Forest"

- "The Theory of Quotation"

- "On the Art of Staying at the Seaside: A Meditation at Eastbourne"

- "Concerning Chess"

- "The Coal-Scuttle: A Study in Domestic Aesthetics"

- "Bagarrow"

- "The Book of Essays Dedicatory"

- "Through a Microscope: Some Moral Reflections"

- "The Pleasure of Quarreling"

- "The Amateur Nature Lover"

- "From an Observatory"

- "The Mode in Monuments: Stray Thoughts in Highgate Cemetery"

- "How I Died"

External links

References

- ^ David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), pp. 35-37. "Most of Wells's ephemeral pieces have not been collected, and many have not even been identified as his. Wells did not automatically receive the byline his reputation demanded until after 1896 or so. Some journals had a policy of giving only one byline an issue, no matter how many pieces an author contributed to it. Wells also occasionally used pseudonyms, although these are ordinarily very easy to spot. His style became increasingly recognizable, and eventually he collected a number of these magazine pieces in two early volumes [Select Conversations with an Uncle and Certain Personal Matters] . . . As a result, many of his early pieces are known. Some knowledge also comes from a list compiled by Jane Wells [i.e. Catherine Robbins Wells, Wells's second wife] in the First World War period. But it obvious that many early Wells items have been lost. . . . Of course, Wells himself may have been unwilling to have some of his early published work reprinted, although the correspondence does not suggest that he was ashamed of much that he wrote" (p. 35).

- ^ "How I Died," the last piece in the collection, written in 1897.

- ^ "Of a Book Unwritten," a speculation about the future evolution of Homo sapiens.

- ^ "How I Died," the volume's concluding piece. The diagnosis of a fatal illness, which came about a month after Wells incurred a serious internal injury while playing rugby on Aug. 30, 1887, proved to be mistaken. Wells describes three phases of his reaction. "My first phase was an immense sorrow for myself. . . . Then presently the sorrow broadened . . . I thought more of the world's loss, and less of my own. . . . This lasted . . . nearly four months," until one day on a springtime walk "I quite forgot I was a Doomed Man. . . . For a moment I tried in vain to think what it was had slipped my memory. Then it came, colourless and remote. 'Oh! Death.... He's a Bore,' I said; 'I've done with him,' and laughed to think of having done with him. 'And why not so?' said I." (These are the concluding words of Certain Personal Matters.)

- ^ David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 35.

- ^ Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie, H.G. Wells: A Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), p. 95.

- ^ David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 35.

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owens, 2010), p. 125.

- ^ David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 37.