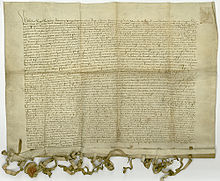

Peace of Thorn (1411)

The (First) Peace of Thorn was a peace treaty formally ending the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War between allied Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania on one side, and the Teutonic Knights on the other. It was signed on 1 February 1411 in Thorn (Toruń), one of the southernmost cities of the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights. In historiography, the treaty is often portrayed as a diplomatic failure of Poland–Lithuania as they failed to capitalize on the decisive defeat of the Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in June 1410.[citation needed] The Knights returned Dobrzyń Land which they captured from Poland during the war and made only temporary territorial concessions in Samogitia, which returned to Lithuania only for the lifetimes of Polish King Władysław Jagiełło and Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas. The Peace of Thorn was not stable. It took two other brief wars, the Hunger War in 1414 and Gollub War in 1422, to sign the Treaty of Melno that solved the territorial disputes. However, large war reparations were a significant financial burden on the Knights, causing internal unrest and economic decline. The Teutonic Knights never recovered their former might.

Background

In May 1409, an uprising started in Samogitia, which had been in Teutonic hands since the Peace of Raciąż of 1404.[1] Grand Duke of Lithuania Vytautas supported the uprising. Poland, which had been in a personal union with Lithuania since 1386, also announced its support to the Samogitian cause. Thus, the local uprising escalated into a regional war. The Teutonic Knights first invaded Poland, catching the Poles by surprise and capturing the Dobrzyń Land without much resistance.[2] However, neither side was ready for a full-scale war and agreed to a truce mediated by Wenceslaus, King of the Romans in October 1409. When the truce expired in June 1410, allied Poland–Lithuania invaded Prussia and met the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald. The Knights were soundly defeated, with most of their leadership killed. Following the battle, most Teutonic fortresses surrendered without resistance and the Knights were left with only eight strongholds.[3] However, the allies delayed their Siege of Marienburg, giving the Knights enough time to organize defense. The Polish–Lithuanian army, suffering from lack of ammunition and low morale, failed to capture the Teutonic capital and returned home in September.[4] The Knights quickly recaptured their fortresses that were taken by the Poles.[5] Polish King Jogaila raised a fresh army and dealt another defeat to the Knights in the Battle of Koronowo in October 1410. Heinrich von Plauen, new Teutonic Grand Master, wanted to continue fighting and attempted to recruit new crusaders. However, the Teutonic Council preferred peace and both sides agreed to a truce, effective between 10 December 1410 and 11 January 1411.[6] Three-day negotiations in Raciąż between Jogaila and von Plauen broke down and Teutonic Knights invaded Dobrzyń Land again.[6] The incursion resulted in a new round of negotiations that ended[citation needed] with the Peace of Thorn signed on 1 February 1411.[7]

Terms

The borders were returned to their pre-1409 state with exception of Samogitia.[8] The Teutonic Order relinquished its claims to Samogitia but only for the lifetimes of Polish King Jogaila and Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas. After their deaths, Samogitia was to return to the Knights. (Both rulers were at the time aged men.[9]) In the south, the Dobrzyń Land, captured by the Knights during the war, was ceded back to Poland. Thus, the Knights suffered virtually no territorial losses – a great diplomatic achievement after the crushing defeat in the Battle of Grunwald.[8][10] All sides agreed that any future territorial disputes or border disagreements would be resolved via international mediation. Borders were open for international trade, which was more beneficial to Prussian cities.[9] Jogaila and Vytautas also promised to convert all remaining pagans in Lithuania, which officially converted to Christianity in 1386, and Samogitia, which was not yet officially converted.[8]

After the Battle of Grunwald, Poland–Lithuania held some 14,000 captives.[11] Most of the commoners and mercenaries were released shortly after the battle on condition that they report to Kraków on 11 November 1410.[12] Only those who were expected to pay ransom were kept in captivity. Considerable ransoms were recorded; for example, the mercenary Holbracht von Loym had to pay 150 kopas of Prague groschens, or more than 30 kg of silver.[13] The Peace of Thorn settled the ransoms en masse: the Polish King released all the captives in exchange for 100,000 kopas of Prague groschen, amounting to nearly 20,000 kilograms (44,000 lb) of silver payable in four annual installments.[9] In the case of the failure to pay one of the installments, the indemnities were to rise by an additional 720,000 Prague groschen. The ransom was equal to £850,000, ten times the annual income of King of England.[14]

Aftermath

In order to raise the money needed to pay the ransom, Grand Master Heinrich von Plauen needed to raise taxes. He called a council of representatives from Prussian cities to approve a special levy. Danzig (Gdańsk) and Thorn (Toruń) revolted against the new tax, but were subdued.[8] The Knights also confiscated church silver and gold and borrowed heavily abroad. The first two installments were paid in full and on time. However, further payments were difficult to collect as the Knights emptied their treasury trying to rebuild their castles and army, which heavily relied on paid mercenaries.[8] They also sent expensive gifts to the Pope and Sigismund of Hungary to ensure their continued support to the Teutonic cause.[15] Tax records indicated that harvest was modest in those years and that many communities fell three years behind their taxes.[16]

Soon after the conclusion of the peace, disagreements arose regarding the ill-defined borders of Samogitia. Vytautas claimed that all territory north of the Neman River, including port city Memel (Klaipėda), was part of Samogitia and thus should be transferred to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[17] In March 1412, Sigismund of Hungary agreed to mediate reduction to the third installment, demarcation of the Samogitian border, and other matters. The delegations met in Buda (Ofen), residence of Sigismund, where lavish feasts, tournaments, and hunts were organized. The celebrations included wedding of Cymburgis of Masovia, Jogaila's niece, to Ernest, Duke of Austria.[18] In August 1412, Sigismund announced that the Peace of Thorn was proper and fair[19] and appointed Benedict Makrai to investigate the border claims. The installments were not reduced and the last payment was made on time in January 1413.[20] Makrai announced his decision in May 1413, allotting the entire northern bank, including Memel, to Lithuania.[21] The Knights refused to accept this decision and the inconclusive Hunger War broke out in 1414. The negotiations continued at the Council of Constance and the dispute was not resolved until the Treaty of Melno in 1422.[citation needed]

Overall, the Peace of Thorn had a negative long-term impact on Prussia. By 1419, 20% of Teutonic land lay abandoned and its currency was debased to meet expenses.[22] Increased taxes and economic decline exposed internal political struggles between bishops, secular knights, and city residents.[23] These political rifts only grew with further wars with Poland–Lithuania and eventually resulted in the Prussian Confederation and civil war that tore Prussia in half (Thirteen Years' War (1454–66)).

References

Citations

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 20

- ^ Ivinskis 1978, p. 336

- ^ Ivinskis 1978, p. 342

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 75

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 166

- ^ a b Turnbull 2003, p. 77

- ^ Riley-Smith, Jonathan Simon Christopher (2005). The Crusades: A History. Yale University Press. p. 254. ISBN 9780300101287.

- ^ a b c d e Turnbull 2003, p. 78

- ^ a b c Urban 2003, p. 175

- ^ Davies 2005, p. 98

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 68

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 69

- ^ Pelech 1987, pp. 105–107

- ^ Christiansen 1997, p. 228

- ^ Urban 2003, pp. 176, 189

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 188

- ^ Ivinskis 1978, p. 345

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 191

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 192

- ^ Urban 2003, p. 193

- ^ Ivinskis 1978, pp. 346–347

- ^ Stone 2001, p. 17

- ^ Christiansen 1997, p. 230

Sources

- Christiansen, Eric (1997), The Northern Crusades (2nd ed.), Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-026653-4

- Davies, Norman (2005), God's Playground. A History of Poland. The Origins to 1795, vol. I (Revised ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5

- Ivinskis, Zenonas (1978), Lietuvos istorija iki Vytauto Didžiojo mirties (in Lithuanian), Rome: Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademija, LCCN 79346776

- Pelech, Markian (1987), "W sprawie okupu za jeńców krzyżackich z Wielkiej Wojny (1409–1411)", Zapiski Historyczne (in Polish), 2 (52), archived from the original on 28 September 2011

- Stone, Daniel (2001), The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Tannenberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights, Campaign Series, vol. 122, London: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-561-7

- Urban, William (2003), Tannenberg and After: Lithuania, Poland and the Teutonic Order in Search of Immortality (Revised ed.), Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, ISBN 0-929700-25-2

External links

Works related to Peace of Thorn at Wikisource (in Latin)

Works related to Peace of Thorn at Wikisource (in Latin)

- 1411 in Europe

- 15th century in Lithuania

- Treaties of the Teutonic Order

- Peace treaties of Poland

- History of Toruń

- 1410s treaties

- Treaties of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569)

- Polish–Teutonic wars

- 15th century in the State of the Teutonic Order

- History of Samogitia

- 15th century in Poland