Typos of Constans

The Typos of Constans (also called Type of Constans) was an edict issued by eastern Roman emperor Constans II in 648 in an attempt to defuse the confusion and arguments over the Christological doctrine of Monotheletism. For over two centuries, there had been a bitter debate regarding the nature of Christ: the orthodox Chalcedonian position defined Christ as having two natures in one person, whereas Miaphysite opponents contended that Jesus Christ possessed but a single nature. At the time, the Byzantine Empire had been at near constant war for fifty years and had lost large territories. It was under great pressure to establish domestic unity. This was hampered by the large number of Byzantines who rejected the Council of Chalcedon in favour of Monophysitism.

The Typos attempted to dismiss the entire controversy, on pain of dire punishment. This extended to kidnapping the Pope from Rome to try him for high treason and mutilating one of the Typos's main opponents. Constans died in 668. Ten years later his son, Constantine IV, fresh from a triumph over his Arab enemies and with the predominantly Monophysitic provinces irredeemably lost, called the Third Council of Constantinople. It decided with an overwhelming majority to condemn Monophysitism, Monotheletism, the Typos of Constans and its major supporters. Constantine put his seal to the Council's decisions, and reunited such of Christendom as was not under Arab suzerainty.

Background

Political background

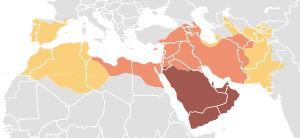

In 628, the Christian Byzantine Empire and the Zoroastrian Sasanian Empire of Iran ended a harrowing twenty-six-year-long war. Both states were completely exhausted. The Byzantines had had the majority of their territory overrun and a large part of it devastated. Consequently, they were vulnerable to the sudden emergence of the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate in Arabia; the Caliphate's forces invaded both empires only a few years after the war. The Muslim, also known as Arab, forces swiftly conquered the entire Sasanian Empire and deprived the Byzantine Empire of its territories in the Levant, the Caucasus, Egypt, and North Africa. By 642, the Muslim armies had conquered all of Syria and Egypt, the richest parts of the Byzantine Empire.[1]

For a variety of reasons, the Byzantine population of Syria did not put up much resistance.[note 1] High taxes, the power of the landowners over the peasants, and the recently ended war with the Persians were some of the reasons why the Syrians welcomed the change. "The people of Homs replied [to the Muslims], 'We like your rule and justice far better than the state of oppression and tyranny in which we were. The army of Heraclius [Byzantium] we shall indeed ... repulse from the city.'"[3] Another key reason for the welcome of the Arabs as rulers by the Christian Syrians and Egyptians, is that they found the strict monotheism of Islam closer to their own Monophysite Christian position than the hated doctrine of Constantinople, which they perceived as bitheism.[4]

On 11 February 641 Heraclius, emperor for 31 years, who had pulled the Empire back from the brink of ruin, died. In the following three years, the Empire endured four short-lived emperors or usurpers before seventeen-year-old Constans II, grand-son of Heraclius, established himself on the throne of the diminished realm.[5] In 643–644, Valentinus led a campaign against the Arabs, but his army was routed, he fled, and his treasury was captured.[5] In 644 or 645, Valentinus attempted to usurp his son-in-law's throne. He failed, the populace of the capital lynching his envoy Antoninos before killing Valentinus himself.[5]The Byzantine Empire seemed to be tearing itself apart with internecine strife, while the "human tsunami"[6] of Arab conquest swept on.[6]

Theological background

The Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, was held in 451 and laid the basis of Christological belief; Christ was a single person possessing two natures: a perfect God and a perfect man united "unconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly and inseparably".[7] This was viewed as outright heresy by Monophysites who, briefly, believe that Jesus Christ is "one person and one hypostasis in one nature: divine".[8] Monophysite belief was widespread in Egypt and, to a lesser extent, Syria.[9] The Byzantine state had repeatedly attempted to stamp it out.[4]

Emperor Heraclius spent the last years of his life attempting to find a compromise theological position between the Monophysites and the Chalcedonians. What he promoted via his Ecthesis was a doctrine which declared that Jesus, whilst he possessed two distinct natures, had only one will; the question of the energy of Christ was not relevant.[10] This approach seemed to be an acceptable compromise, and it secured widespread support throughout the east. Pope Honorius I and the four Patriarchs of the East – Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem – all gave their approval to the doctrine, referred to as Monothelitism, and so it looked as if Heraclius would finally heal the divisions in the church.[11]

The Popes in Rome objected. Pope Honorius I died in 638 and his successor Pope Severinus condemned the Ecthesis outright, and so was forbidden his seat by Constans until 640. His successor Pope John IV also rejected the doctrine completely, leading to a major schism between the eastern and western halves of the Catholic Church. When news of the Pope's condemnation reached Heraclius, he was already old and ill, and the news is said to have hastened his death.[12]

Meanwhile, there were problems in the province of Africa. Since the fall of Egypt it was in the front line against Arab expansionism. Nominally a Byzantine province, in practice Africa was all but independent and a hotbed of dissent to Constantinople's Monotheletist policies. The threat of imminent invasion increased the local bishops' antipathy to Monophysitism, knowing that its adherents in Syria and Egypt had welcomed the invading Arabs. The compromise policy of Monotheletism was disliked as giving comfort to those seen theologically as heretics and politically as potential traitors. A monk named Maximus the Confessor had long carried on a furious campaign against Monotheletism, and in 646 convinced an African council of bishops, all resolutely Chalcedonian, to draw up a manifesto against it. This they forwarded to the new pope, Theodore I, who in turn wrote to Patriarch Paul II of Constantinople, outlining the heretical nature of the doctrine. Paul, a devoted Monothelete, replied in a letter directing the Pope to adhere to the doctrine of one will. Theodore in turn excommunicated the Patriarch in 649, declaring Paul a heretic. The divisions in Byzantine society and the open opposition to imperial authority were starkly exposed.[13][14]

Constans issues the Typos

Constans II was a young man of seventeen, and he was supremely indifferent to the religious debates convulsing the Church.[15] However, he was certainly concerned about the effect the arcane debate was having on his empire. A key reason for the parlous position of the Byzantine Empire was the religious divide. He had just established an uncertain truce with the Arabs, and badly needed to rebuild his forces and to gain the full support of his empire. So he issued an imperial edict, called the Typos (Greek: τύπος, romanized: typos) in 648.[note 2] This edict made it illegal to discuss the topic of Christ possessing either one or two wills, or one or two energies; or even to acknowledge that such a debate was possible. He declared that the whole controversy was to be forgotten.[15]

During the proceedings of the Lateran Council of 649 the text of the Typos was read out in full and so is preserved in the recorded Acts. The first section expresses concern that some subjects of the empire consider Christ to have had one will, and some that he had two. This is discussed, and concluded with the observation that the debate is dividing society and that Constans intends to put a stop to this.[17]

The Typos goes on to deny people "the licence to conduct any dispute, contention or controversy",[17] explaining that whole matter has been settled by the five previous ecumenical councils "and the straight forwardly plain statements... of the approved holy fathers".[17] The right of any individual to interpret their findings is explicitly forbidden. "The situation that existed previously... is to be maintained everywhere, as if no quibbling had arisen over them."[17] There is to be an amnesty for any past comments on the topic, and all writings regarding it are to be destroyed.[17]

In the third and final section, various penalties were prescribed for anyone who disobeys the imperial decree. Bishops or clerks of the church are to be deposed. Monks are to be excommunicated, while public servants or military officers are to lose their office. Private citizens of senatorial rank would have their property confiscated. Finally, if any of the great mass of the citizenry so much as mentioned the topic, they would face corporal punishment and banishment for life.[12]

Opposition

In Rome and the west, the opposition to Monotheletism was reaching fever pitch, and the Typos of Constans did nothing to defuse the situation; indeed it made it worse by implying that either doctrine was as good as the other.[15] Theodore planned the Lateran Council of 649 to condemn the Ecthesis, but died before he could convene it; his successor, Pope Martin I, did. Not only did the Council condemn the Ecthesis, it condemned the Typos as well. After the synod, Pope Martin wrote to Constans, informing the emperor of its conclusions and requiring him to condemn both the Monothelete doctrine and his own Typos. However, Constans was not the sort of emperor to take such a rebuke of imperial authority lightly.[18]

Constans sent a new Exarch of Ravenna, Olympius, who had authority over all Byzantine territory in Italy, which included Rome. He had firm instructions to ensure that the Typos be followed in Italy, and to use whatever means necessary to ensure that the Pope adhere to it.[19] Arriving while the Lateran Synod was sitting, he realised how opposed the west was to the emperor's policy and set up Italy as an independent state; his army joined his rebellion. This made it impractical for Constans to take effective action against Pope Martin, until after Olympius died three years later.[20]

Constans appointed a new Exarch, Theodore I Calliopas, who marched on Rome with the newly loyal army, abducted Pope Martin and brought him to Constantinople where he was tried for high treason before the Senate; he was banished to Chersonesus (present-day Crimea)[21] and shortly after died as a result of his mistreatment.[22] In an unusual move, a successor, Pope Eugene I, was elected in 654 by the College of Cardinals while Martin I still lived. The new pope normalized relations with Constantinople, and although he avoided pressing the issues of the Christological controversy, he ceremonially refused to accept a letter from the Patriarch of Constantinople when the imperial emissary attempted to deliver it.[23] Constans viewed settling the dispute as a matter of state security, and persecuted anyone who spoke out against Monotheletism, including Maximus the Confessor and a number of his disciples. Maximus was tortured over several years; he lost his tongue and his right hand as Constans attempted to force him to recant. Constans even personally journeyed to Rome in 663 to meet with the Pope, the first emperor to visit since the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[24]

Condemnation

With Constans' death in 668, the throne passed to his son Constantine IV. Pope Vitalian, who had hosted the visit of Constans II to Rome in 663, almost immediately declared himself in favour of the doctrine of the two wills of Christ, the orthodox Chalcedonian position. In response, Patriarch Theodore I of Constantinople and Macarius, Patriarch of Antioch, both pressed Constantine to take measures against the Pope. Constantine, however, was fully occupied with military matters and saw no profit in reigniting this debate. In 674, the Arabs commenced the great siege of Constantinople which lasted four years before they were defeated. With the pressure from external enemies at least temporarily relieved, Constantine was able to turn to church affairs. With the predominantly Monophysitist provinces permanently lost to the Arabs, he was under less pressure to support any compromise which included their position.[25]

He decided to put the Monotheletic question to a Church Council. Constantine suggested this to the Pope in 678, and the proposal was welcomed.[26] This council, the Sixth Ecumenical Council, met for ten months from 680 to 681. It hosted 174 delegates from every corner of Christendom. The Patriarchs of Constantinople and Antioch were present in person, while the Pope and the Patriarchs of Alexandria and Jerusalem sent representatives. It held 18 plenary sessions; Constantine chaired the first 11, carefully expressing no opinion. On 16 September 681, it nearly unanimously condemned the Monotheletic doctrine and the Typos of Constans, with the exception of two delegates. Constantine personally signed the final declaration and was hailed as Destroyer of Heretics. Monotheletism was outlawed, and the non-Arab Christian world was united.[27][28]

One of the patriarchs anathematised (excommunicated) as heretics for their support of the Typos was Pope Honorius.[29] The issue of a Pope being disowned by his own successors has caused difficulty for Catholic theologians ever since, especially when discussing papal infallibility.[30][31]

See also

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- ^ Hugh N. Kennedy notes that "the Muslim conquest of Syria does not seem to have been actively opposed by the towns, but it is striking that Antioch put up so little resistance".[2]

- ^ Modern historian Salvatore Consentino suggests that it may have been issued as late as spring 649.[16]

Citations

- ^ Norwich 1988, pp. 300–302, 304–305.

- ^ Kennedy 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, The Battle of the Yarmuk (636) and after Archived 11 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Norwich 1988, pp. 304–305.

- ^ a b c Lilie et al pp. 70–71

- ^ a b Howard-Johnston (2006), xv

- ^ Norwich 1988, p. 156.

- ^ Martin Lembke, lecture in the course "Meetings with the World's Religions", Centre for Theology and Religious Studies, Lund University, Spring Term 2010.

- ^ After Chalcedon – Orthodoxy in the 5th/6th Centuries Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bury 2005, p. 251.

- ^ Norwich 1988, p. 309.

- ^ a b Norwich 1988, p. 310.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 312.

- ^ Bury 2005, p. 292.

- ^ a b c Bury 2005, p. 293.

- ^ Consentino 2014, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b c d e Price, Booth & Cubitt 2016, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Norwich 1988, p. 318.

- ^ Bury 2005, p. 294.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1957, p. 107.

- ^ Siecienski 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Bury 2005, p. 296.

- ^ Ekonomou, 2007, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1957, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1957, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Bury 2005, p. 314.

- ^ Norwich 1988, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1957, p. 115.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1957, p. 114.

- ^ Norwich 1988, p. 326.

- ^ Herbermann 1913.

Sources

- Bury, John B. (2005). A history of the later Roman empire from Arcadius to Irene. Vol. 2. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4021-8368-3.

- Consentino, Salvatore (2014). "Constans II, Ravenna's Autocephaly and the Panel of the Privileges in St. Apollinare in Classe: A reappraisal". In Kolias, T. G.; Pitsakis, K. G. & Synellis, C. (eds.). Aureus. Volume dedicated to Professor Evangelos K. Chrysos. Athens: Institouto Historikōn Ereunōn. ISBN 978-960-9538-26-8.

- Ekonomou, Andrew J., Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern influences on Rome and the papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752. Lanham, MD. Lexington Books. (2007) ISBN 978-0-7391-1977-8

- Herbermann, Charles George (1913). "Pope Honorius I". The Catholic Encyclopedia: an International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. New York: Encyclopedia Press.

- Howard-Johnston, J.D., East Rome, Sasanian Persia and the End of Antiquity : Historiographical and Historical Studies. Farnham : Ashgate (2006) ISBN 978-0-86078-992-5

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (2003). Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81459-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2006). The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East. Variorum Collected Studies. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5909-9.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes; Ludwig, Claudia; Pratsch, Thomas; Zielke, Beate (2001). "Ualentinos (#8545)". Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit: 1. Abteilung (641–867), Band 5 : Theophylaktos (# 8346) – az-Zubair (# 8675), Anonymi (# 10001–12149) (in German). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 69–73. ISBN 978-3-11-016675-0.

- Norwich, John Julius (1988). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-80251-7.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1957). History of the Byzantine State. Translated by Hussey, Joan. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. OCLC 2221721.

- Price, Richard; Booth, Phil & Cubitt, Catherine (2016). The Acts of the Lateran Synod of 649. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-78138-344-5.

- Siecienski, Anthony Edward (2010). The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537204-5.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2630-6.