Joseph Brummer

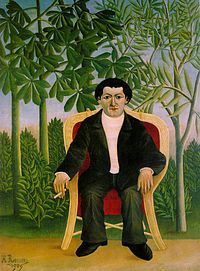

Portrait of Joseph Brummer by Henri Rousseau, 1909, now in the National Gallery, London | |

| Founded | 1914 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Joseph Brummer Irme Brummer |

| Defunct | 1949 |

| Headquarters | , United States |

Key people | Joseph Brummer, Ernest Brummer |

| Products | Fine arts |

| Owner | Imre and Joseph Brummer |

Joseph Brummer (1883 – 14 April 1947) was a Hungarian-born art dealer and collector who exhibited both antique artifacts from different cultures, early European art, and the works of modern painters and sculptors in his galleries in Paris and New York. In 1906 he and his two brothers opened their first gallery in Paris, the Brummer Gallery. At the start of World War I, they closed the gallery and moved to New York City. Joseph alone opened his next gallery in 1921 in Manhattan.

Biography

Joseph (originally József) Brummer was born in Sombor, then in Hungary (now Serbia), in 1883. He studied applied arts in Szeged from 1897 on, and continued these studies in Budapest from 1899 on. Afterward, he studied at Munich before starting on his own as an artist in Budapest and Szeged.

Together with his brothers Ernest (1891-1964) and Imre (died 1928), he moved to Paris in 1905. In 1906, Brummer and his brothers opened the Brummer Gallery in Paris at the Boulevard Raspail, where they sold African art, Japanese prints and pre-Columbian, mainly Peruvian art, alongside contemporary paintings and sculptures.[1]

During the autumn of 1908, he shared a studio space at Cité Falguière with avant-garde sculptor Joseph Csaky, who was also from Szeged and Budapest.[2] Brummer studied sculpture under Jules-Felix Coutan, Auguste Rodin and in 1908 Henri Matisse. He also attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and thus got to know contemporary artists.

At the start of World War I, Joseph Brummer closed in Paris and moved to New York City. In 1921 he reopened a gallery at 43 East Fifty-Seventh Street in Manhattan. He specialized in medieval and Renaissance European art, and Classical, Ancient Egyptian, African, and pre-Columbian objects, but also hosted some of the earliest exhibitions of modern European art in the United States. It stayed in business until 1949, two years after Joseph's death.[3]

A major part of his private art collection was bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1947.[4] A second part of the Joseph Brummer art collection, still over 2400 lots, was sold in 1949 by Parke-Bernet Galleries.

The final part, 600 pieces that remained in the family, were sold in Zurich in October 1979. These pieces were eventually inherited by Ernest Brummer's widow, Ella Bache Brummer. Their value was estimated at $10 million.[5]

From 1931 until 1948, Brummer had owned the Guennol Lioness; in 2007 it was the most expensive sculpture ever sold at auction.[6][7]

In 1909 Brummer had his portrait painted by Henri Rousseau.[8] and by Anne Goldthwaite in 1915.[9] In 1993, the Rousseau portrait was sold by Christie's for £2,971,500 ($4,421,592).[10] It is currently owned by the National Gallery.

Gallery

The New York branch of the Brummer Gallery was opened in 1914 by Imre and Joseph Brummer. Joseph and his brothers Ernest were among the most significant art dealers of the first half of the 20th century, dealing in a broad range of art that spanned from classical antiquity to modern art.[11] Their collection included many works from the Middle Ages, Pre-Columbian America, and Renaissance and Baroque decorative arts.[12] Following Joseph Brummer's death in 1947, the gallery closed down in 1949, and its collection was auctioned off over the next three decades.[11]

Exhibitions

This is an incomplete list of the exhibitions of modern art in the Brummer Gallery in New York.

- 1921, 4 to 23 April: Maurice Prendergast

- 1921, May: "Works by French and American artists including paintings by Jennie Van Fleet Cowdery", including two works by Auguste Renoir

- 1921, 24 October to 21 November: Anne Goldthwaite[3]

- 1921, 28 November to 24 December: Frank Burty

- 1922, 3 to 21 January: Peggy Bacon and Alexander Brook

- 1922: sculptures by Henri Matisse and Manolo Hugué, and paintings by Amedeo Modigliani, André Derain, Maurice Utrillo, Marie Laurencin and Pascin[3]

- 1922 December 15 to 1923, 13 January: Auguste Rodin (paintings and sculptures)

- 1923: 17 January to 10 February: Pascin

- 1923, 17 March to 14 April: Thomas Eakins[3]

- 1923: Bernard Karfiol

- 1923, 22 October to 10 November: Toshi Shimizu

- 1923, 15 December to 1924, 5 January: Works by Max Jacob[3]

- 1924, 25 February to 22 March: Henri Matisse

- 1924: Hermine David

- 1924: José de Togores

- 1924, 4 to 27 December: Georges Seurat

- 1925, January: Roger Fry

- 1925, February: Walter Pach

- 1925, 2 to 21 March 1925: Michel Kikoine

- 1925: Bernard Karfiol (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1926, 18 January to 13 February: Aristide Maillol

- 1926, 17 November to 15 December: Sculptures by Constantin Brâncuși.[13]

- 1927, 17 January to 12 February: Béla Czóbel

- 1927, 14 February to 12 March: Bernard Karfiol (third exhibition at Brummer)

- 1927, March to 9 April: Eugène Zak

- 1927, late: First personal exhibition of works by Charles Despiau

- 1928, 1 to 25 February: John Storrs

- 1928, 27 February to 24 March: Gaston Lachaise

- 1928, 26 March to 21 April: Jacques Villon, paintings

- 1929, 16 February to 16 March: A. S. Baylinson and Morris Kantor

- 1929, 18 March to 13 April: Jane Berlandina

- 1929, 28 March to 12 April: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, sculptures

- 1929, May: Michel Kikoine (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1929, 1 to 28 November: "Portraits of Maria Lani by Fifty-One Painters", featuring work by Chaïm Soutine, Kees van Dongen, Georges Rouault, Pierre Bonnard, Rodolphe-Théophile Bosshard, Charles Despiau, Henri Matisse, Man Ray, André Derain, and others[14]

- 1929, 30 November to 13 December: collection of Albert Eugene Gallatin, including work by Fernand Léger, Man Ray, Paul Klee, André Masson, Joan Miró, Joseph Stella, and a 1906 self-portrait by Pablo Picasso

- 1929, 14 December to 1930, 31 January: Othon Friesz, Paintings

- 1930, 1 to 28 February: Max Jacob (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1930, 8 to 31 March: Jane Berlandina (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1930, 1 April to 3 May: Georges Rouault

- 1930, 20 October to 20 November: Jacques Villon (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1930, 22 November to 20 December: Pierre Roy

- 1931, 5 January to 7 February: Henri Matisse, sculptures

- 1931, 13 to 28 February: Anne Goldthwaite (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1931, 16 March to 18 April: Théophile Steinlen

- 1931, 13 October to 7 November: Marcel Mouillot

- 1931, 9 November to ?: Charles Dufresne

- 1932, 9 to 29 February: Arthur Everett Austin, Jr.

- 1932, 5 March to 5 April: Josep Llorens i Artigas

- 1932, November to 10 December: Maurice Marinot, glass

- 1932, 13 December to ?: 18th century French drawings, from the Richard Owen collection

- 1933, 3 January to 28 February: Aristide Maillol (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1933, 4 March to 15 April: Pierre Roy (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1933, October to November: 18th and 19th century French drawings from the Richard Owen collection (second part), including works by Antoine Watteau, Gustave Moreau and Théophile Steinlen

- 1933, 17 November to 1934, 13 January: Sculptures by Constantin Brâncuși (second exhibition at Brummer).[15]

- 1934, 24 February to 15 April: Pablo Gargallo

- 1934, 5 November to 29 December: Charles Despiau (second exhibition at Brummer)

- 1935, 5 January to 28 February: André Dunoyer de Segonzac

- 1935, 15 March to 11 May: Mateo Hernandez

- 1935, October: Marguerite Zorach

- 1935, 2 December to 1936, 31 January: first US exhibition of Jacques Lipchitz

- 1936, 2 March to 4 April: Béla Czóbel

- 1936, 9 November to 1937, 2 January: André Derain

- 1937, 25 January to 20 March: Ossip Zadkine

- 1937, 1 November to 31 December: François Pompon

- 1938, February and March: Léon Hartl

- 1938, 7 to 28 November: Charles Dufresne (second Brummer exhibition)

- 1938: 7 November to 1939, 7 January: Henri Laurens

Notes

- ^ Carder, James N. (2010). A Home of the Humanities: The Collecting Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss. Harvard University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-88402-365-4. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Edith Balas, 1998, Joseph Csaky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture, American Philosophical Society

- ^ a b c d e "Brummer Gallery". Gilded Age. New York Art Resources Consortium. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "RARE ART BOUGHT BY METROPOLITAN; Group, Valued at $1,000,000, Contains the Major Part of Brummer Collection". The New York Times. 16 September 1947. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "American's $10-million art collection on block". Rome News-Tribune. UPI. 27 September 1979. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "Lion sculpture gets record price". BBC News. 6 December 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Baugh, Maria (12 December 2007). "Antiquities: The Hottest Investment". TIME. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Picture by Ridiculed Artist May Fetch Millions". Daily News. Reuter. 6 October 1993. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Dohme Breeskin, Adelyn (1982). Anne Goldthwaite: a catalogue raisonné of the graphic work. Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-89280-019-3. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ "Henri Rousseau, called "Le Douanier"". Christie's. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Documenting the Gilded Age: New York City Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century: Phase I | Galleries and Artists Clubs : Brummer Gallery". Gildedage.omeka.net. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Carter, Michael (December 18, 2013). "New Collection: The Brummer Gallery Records | Highlights from the Digital Collections". Libmma.org. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Brancusi: catalogue : of exhibition November 17-December 15, 1926. Brummer Gallery. 1926. p. 44.

- ^ "Art: 51 Portraits". Time. 18 November 1929. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Brancusi: exhibition November 17, 1933 - January 13, 1934. Brummer Gallery. 1933.

Further reading

- Bruzelius, Caroline Astrid; Jill Meredith (1991). The Brummer Collection of Medieval Art. Duke University Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-8223-1055-6. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

External links

- The Brummer Gallery Records, over 13,000 digitized object cards from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Walters Art Museum objects with provenance from Joseph Brummer

- Metropolitan Museum of Art objects with provenance from Joseph Brummer

- The Frick Collection research information

- Article on The Brummer Gallery Records from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries.

- Documenting the Gilded Age: New York City Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century. A New York Art Resources Consortium project. Brummer Gallery exhibition catalogs.

- Oral history interview with Dr. John Laszlo, 2015 Dec. 6 from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York.