George Keats

George Keats | |

|---|---|

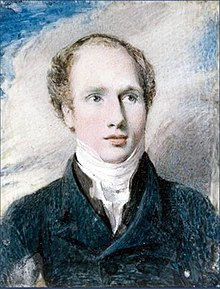

Portrait of George Keats by Joseph Severn, 1817 | |

| Born | 28 February 1797 |

| Died | 24 December 1841 (aged 44) |

| Resting place | Cave Hill Cemetery Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse | Georgiana Augusta Wylie |

| Children | 8 |

| Relatives | John Keats (brother) |

George Keats (28 February 1797 – 24 December 1841) was an American businessman and civic leader in Louisville, Kentucky, as it emerged from a frontier entrepôt into a mercantile centre of the old northwest. He was also the younger brother of the Romantic poet John Keats.

During the years from 1821 to 1841, Keats led a philosophical society, meant to overcome Louisville's raw culture, operating a literary salon in his living room which evolved into the Lyceum and then into the board of Louisville College, the precursor to the University of Louisville.[1]

In 1827, Keats was elected to the Ohio Bridge Commission, laying the foundation for the river's first crossing.[2] The state government appointed him to the board of the Bank of Kentucky in 1832.[3] He joined the boards of ten other organisations, including the Kentucky Historical Society and the Harlan Museum, which he headed. In 1841, he was elected to the city council.[4]

Life

Keats, a younger brother of John Keats, was likely born in London's Moorfields district above the Swan and Hoop inn, owned by his grandfather John Jennings and managed by his father Thomas Keats. George had two other siblings: Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez. Another brother was lost in infancy. By 1800 the family moved to Craven Street, a mile away in Hackney. When George was six, and his brother John eight, they were sent to John Clarke's liberal school in Enfield.[5] After visiting the boys, their father was killed in a late-evening riding accident 15 April 1804.[6] Ten weeks later, the boys' mother Frances Jennings Keats married William Rawlings, abandoning her children, including younger siblings Tom and Fanny, to live with her parents, retired in Edmonton.[7] George was the future poet's closest friend and helpmate through Clarke's School in Enfield.

Grandfather Jennings died 8 March 1805. Their mother Frances Rawlings returned to her mother, destitute and disease-ridden, to die of consumption before 10 March 1810. Their grandmother Alice Whalley Jennings relinquished custody to guardians, including Richard Abbey, in July 1810 and subsequently died before 19 December 1814. Abbey removed the boys from Clarke's school, apprenticing John Keats to Thomas Hammond, an Edmonton surgeon, and taking George Keats into his tea wholesaling business on Pancras Lane off London's Poultry street. George, thirteen, lived in a dormitory above Abbey's counting house, while sister Fanny stayed in the Abbeys' suburban home in Walthamstow.[8]

In the fall of 1815 John Keats moved to London, registering at Guy's Hospital for courses in dressing, a step towards licensure as a surgeon. George and John maintained an active social life, in part revolving around John's increasing interest in poetry and his involvement with the Leigh Hunt circle. During these years George was an important helpmate and influence on the poet, acting as an agent, dealing with John's publisher, and serving as a house manager for the three siblings, including their sickly brother Tom. By the end of 1816 and into 1817, George quit Abbey's employment, John abandoned medicine for poetry, the boys left a noisy and smoky Cheapside for Hampstead, and George became engaged to Georgiana Augusta Wylie (c. 1797 – 3 April 1879).[9]

Migration to America

George and Georgiana were married 28 May 1818 at St Margaret's, Westminster. He claimed a portion of his inheritance, which he deemed inadequate to start a business in London, and laid plans to acquire farmland in southern Illinois, seeking an American fortune. In June 1818 the couple departed London for Liverpool, accompanied by John Keats and his friend Charles Brown, who were setting forth on a Scottish walking tour. George and Georgiana booked passage for Philadelphia on the Telegraph.[10]

The Keatses disembarked in late August 1818, journeying by wagon to Pittsburgh and by keelboat down the Ohio River to Henderson, Kentucky. After traveling to nearby Edwards County, Illinois, to see their prospective investment in Morris Birkbeck's community of Wanborough, George dropped the idea and instead spent the winter in John James Audubon's home in Henderson. Keats's experience may have served as a model for Charles Dickens' Martin Chuzzlewit, who also decided he was unprepared for sod-busting.[11] He invested many of his funds in an Audubon steamboat venture, the Henderson, which failed immediately. Audubon's brother-in-law, Thomas W. Bakewell, then persuaded the Keatses to move to Louisville, Kentucky, in early 1819, to work in his sawmill there.[12]

Settling in Louisville

During 1819, Keats bought into the Bakewell & Prentice sawmill, invested in a second steamboat, and learned of the 1 December 1818 death of his brother Tom to consumption. Strapped for cash, he borrowed passage back to London to claim his share of Tom's estate and to settle accounts with John. The visit with John was strained. George met John's love Fanny Brawne, without forming a positive impression. His and John's financial settlement left questions that plagued George for years thereafter. He left London 28 January 1820, and five days later John hemorrhaged blood, beginning his "posthumous year."

As he descended toward death, John Keats removed to Rome in search of a better climate. Broke, he was dependent on gifts and loans from friends, who thought that George should be contributing more from America. John died 23 February 1821. George ultimately settled all John's debts, but Charles Brown maligned him for twenty years, suggesting that he had deprived the poet of necessary funds.[13]

During the 1820s, the Louisville & Portland Canal was completed, and as the city developed, so did the George Keats's sawmill venture. He expanded into property development, ultimately involving over thirty-five developments along Louisville's Main and Jefferson Streets. Always working with partners, including Daniel Smith and John J. Jacob,[14] Keats culminated his building activities with the Louisville Hotel, built in 1835. He built a large home on the Jacobs' lot off Walnut Street, dubbed the "Englishman's Palace".[14]

The Keatses arrived in America as nominal Anglicans, but later joined the nascent Unitarian church, hosting its young leader James Freeman Clarke for a year in their household.[15] At the same time Keats befriended the newspaper editor, George Dennison Prentice.[16]

Although the Keats circle of London friends were liberals who abhorred slavery, George rented slaves for his mill, due to the lack of available white labour. He eventually owned three household slaves. His political views shifted towards Whiggery, especially anti-Jackson. In 1841, Keats completed his assimilation into Louisville's establishment by winning election to the City Council.[17]

Death

Keats endorsed the notes of friends, including Thomas W. Bakewell, who had committed to build a large passenger steamboat. Caught up in the Panic of 1837, Bakewell defaulted, leaving Keats to reimburse the Portland Dry Dock Co. Keats liquidated his holdings to do so, but before he could restore his finances, he succumbed to a gastrointestinal ailment, dying on Christmas Eve 1841. His extensive library included many of John Keats's best letters, as well as Audubon's Ornithology, which would fetch over $1 million in contemporary dollars. George Keats' body was buried in Louisville's Cave Hill Cemetery.[18]

Family

The Keatses' eight children were:[19]

| Name | Life |

|---|---|

| Georgiana Emily (Gwathmey) | June 1819 – bef. 17 June 1855 |

| Rosalind | 18 December 1820 –2 April 1826 |

| Emma Frances (Speed) | 25 October 1823 – 10 September 1883 |

| Isabel | 28 February 1825 – 20 October 1843 |

| John Henry | November 1827 – 7 May 1917 |

| Clarence George | February 1830 – 19 February 1861 |

| Ella (Peay) | 2 March 1833 – 12 March 1888 |

| Alice Ann (Drane) | 1836 –15 June 1881 |

After George's death, Georgiana married John Jeffrey (2 June 1817 – 15 February 1881), 20 years younger than George, in 1843, moving with him to Cincinnati, Ohio and to Lexington, Kentucky, where she died.

Emma Speed met Oscar Wilde when he lectured in Louisville in 1882, and later sent him an autograph manuscript by her uncle John Keats of his poem 'Sonnet on Blue'.

Isabel Keats died, a likely suicide, in the family home months after her mother's remarriage.[20] The descendants of Georgiana, Emma, Ella, and Alice ultimately numbered over 500.[21]

Legacy

Reputation

James Freeman Clarke contributed a memorial sketch of George Keats to The Dial, edited by Ralph Waldo Emerson, in 1843. He wrote, in part, "He was one of the most intellectual men I ever knew. I never saw him when his mind was inactive. It was strange to find, in those days, on the banks of the Ohio, one who had successfully devoted himself to active pursuits, and yet retained so fine a sensibility… The love of his brother, which continued through his life to be among the deepest affections of his soul, was a pledge of their reunion again in another world."[22] Clarke and others continued to defend George's character decades later.

The City of Louisville honored his accomplishments by naming a residential street Keats Avenue.

Creating John Keats's legacy

After his death, the poet's friends, including Charles Brown, Leigh Hunt and Percy Bysshe Shelley, discussed publication of a "Life and Letters" of John Keats, whereas his publisher John Taylor was reluctant to part with copyrights without a participation, which the others rejected. George Keats held John's best letters, and knowledge of the family story, while Brown owned a half-interest in a final Keats effort, a play. None could agree on who should prepare the legacy, until 1841 when George released his threatened injunction against Brown, who in turn handed his materials over to Richard Monckton Milnes, who never knew the poet.[23] After George's death, John Jeffrey transcribed the poet's letters for Milnes, and in 1848 the latter published The Life, Letters, and Literary Remains of John Keats. Milnes's volumes were sufficiently thorough to make up for George's inability to publish a volume of his own.[24]

References

- ^ Crutcher, Lawrence M. (2012). George Keats of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. p. 226.

- ^ Johnston, J. Stoddard (1896). Memorial History of Louisville, vol. I. American Biographical Publishing Co. pp. 77–8.

- ^ Duke, Basil W. (1895). History of the Bank of Kentucky 1792-1895. John P. Morton & Company.

- ^ M. Joelin (1875). Louisville, Past and Present. John P. Morton & Co. p. 26.

- ^ Lowell , Amy (1925). John Keats, vol. I. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 3–71.

- ^ Haynes, Jean (1963). "A Coroner's Inquest, Apr. 1804" in the Keats Shelley Memorial Bulletin, vol. 14. p. 46.

- ^ Gittings, Robert (1968). John Keat. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Gittings, pp. 34–5

- ^ Crutcher, Lawrence M (2012). George Keats of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. p. 48.

- ^ Walker, Carol Kyros (1992). Walking North With Keats. Yale University Press. pp. 8–11. ISBN 9780300048247.

- ^ Dickens, Charles (1841–1844). Martin Chuzzlewit. Chapman & Hall.

- ^ Ford, Alice (1988). John James Audubon. Abbeville Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780896597440.

- ^ Gittings, pp. 377–80

- ^ a b Crutcher, Lawrence M. George Keats of Kentucky: A Life, pp. 224 ff. University Press of Kentucky (Lexington), 2012. Accessed 16 October 2013.

- ^ Clarke, James Freeman (August 1843). "Memorial Sketch of George Keats". The Dial: 221–42.

- ^ Rollins, Hyder Edward (1965). The Keats Circle, vol. I. Harvard University Press. p. cviii.

- ^ M. Joelin (1875). Louisville, Past and Present. John P. Morton & Co. p. 26.

- ^ Crutcher (2012), p. 255

- ^ Crutcher (2012), pp. 269–70

- ^ Rule, Lucian V. in Lyman P. Powell, Editor (1900). Historic Towns of the Southern States. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 528–30.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crutcher, Lawrence M (2009). The Keats Family. Butler Books. p. 318.

- ^ Clarke, p. 229

- ^ Stillinger, Jack (1966). The Letters of Charles Armitage Brown. Harvard University Press. p. 408.

- ^ Milnes, Richard Monckton (1848). Life, Letters, and Literary Remains of John Keats, vol.I. Edward Moxon. p. xxxvi, also II: 39–45.