Ahidnâme

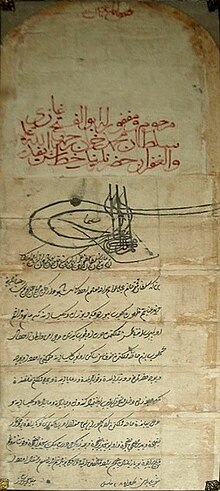

An Ahdname, achtiname or ahidnâme (meaning the "Bill of Oath") is a type of Ottoman charter commonly referred to as a capitulation. During the early modern period, the Ottoman Empire called it an Ahidname-i-Humayun or an imperial pledge and the Ahdname functioned as an official agreement between the Empire and various European states.[1]

Historical background

The Ahdname still requires much detailed study regarding its historical background and about what type of document it was. What is known however is that the Ahdname was an important part of Ottoman diplomacy in that it set forth a contractual agreement between two states, usually between the Ottoman Empire and European nations, like Venice.[2] It was influential in the way it helped to structure society and maintained the agreements made between nation states.[3]

In Venice, Adhnames were also used to maintain political and commercial links with the Ottoman Empire. This agreement between Venice and the Ottoman Empire ensured that Italian merchants were protected during their commerce trips into the Empire. These Ahdnames also provided a certain level of physical protection as they helped provide Italian merchants with hospice.[4] After all, Venice was very aware that in order to protect the strength of their commerce, it was imperative to remain to in good standing with the Ottoman Empire.[5]

By the 16th Century, Venice aimed its policy towards the preservation of peaceful relations with the Ottomans. After the 1453 Conquest of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire had become Europe's most powerful force. As a result, Venice had to tread carefully in order not to instigate any conflicts. Ahdnames became a useful tool in communication between the two competing forces.[6]

The majority of the Ahdnames that the Ottoman Empire and Venice drafted always occurred after a war between the two, such as the two wars they were embroiled in during 1503 and 1540. The remaining treaties were simply edited for better quality and protection willingly by both the Empire and Venice.[7]

Structure of the Ahdname

The Ottoman Ahdname was typically broken down into several sections. Every Ahdname usually had several parts called the erkan (sing. rukn), which were deemed to be the internal structuring of the document.[8] Not every Ahdname had similar erkan however. Instead the text was found between two protocols calls the introductory protocol and the final protocol or eschatocol.[8]

The introductory protocol, main text, and eschatocol consisted of the several erkan:

- The invocation, where the name of God appeared

- The intitulatio, where the name and rank of the person to whom the document was meant for appeared. His official title and rank also appeared.

- The inscriptio, where addresses of the person to whom the document was issued for appeared.

- The salutatio, where the formal greeting appeared.[8]

Then, the Ahdname would continue on with the main text of the document and would include the following erkan:

- The expositio-narratio, where an explanation for the document is issued and any other events are described in detail.

- The dispositio, where a decision that has been made is detailed.

- The sanctio, which is both a confirming of the dispositio as well as a warning. At times it also functioned as an oath.

- The corroboratio, which was an authentication of the document in question. It was an examination of the validity of the Ahdname.

- The datatio, which was the date of which the document was issued to its receiver.

- The locatio, which was the place in which the document was issued.

- The legitimatio, which was again another form of authentication of the document.

Often, the authenticator was the Sultan or the Grand Vizier or simply a seal. This is the final part of the Ahdname to be written, so it is part of the eschatocol.[9] It is important to note, that while this was the general makeup of the Ahdnames, it was not always stringently followed as such.

Historian, Daniel Goffman, writes that those that composed Ahdnames seemed to have, "drawn upon Islamic, sultanic, and even local legal codes as the situations warranted."[10]

List of Venetian Ahdnames

- (1403), Suleyman Celebi

- (1403), Suleyman Celebi

- (1411), Musa Celebi

- (1419), Mehmed I

- (1430), Murad II

- (1446), Mehmed II

- (1451), Mehmed II

- (1454), Mehmed II

- (1479), Mehmed II

- (1482), Bayezid II

- (1503), Bayezid II

- (1513), Selim I

- (1517), Selim I

- (1521), Suleiman I

- (1540), Suleyman I

- (1567), Selim II

- (1573), Selim II

- (1575), Murad III

- (1576), Murad III

- (1595), Mehmed III

- (1604), Ahmed I

- (1619), Osman II

- (1625), Murad IV

- (1641), Ibrahim I[11]

Examples of Ottoman Ahdnames

- In 1454, Mehmed II gave the new Patriarch of Constantinople a new charter for the Greek Orthodox Church and the Greek Orthodox millet.

- In 1458, the Ottoman Empire imposed an Ahdname on the Republic of Ragusa, Dalmatia that closely resembled the one they have given to Venice earlier. The city of Ragusa was required to give up their sovereignty to the Ottoman Empire because they had become a tributary state of the Empire.

- In 1470, Mehmed II also gave rulers from the Republic of Genoa a document that guaranteed freedom if they performed a tribute for the Ottomans.

- In the 1620s, the Ottoman government presented an Ahdname to Ottoman Catholic monks to visit the Balkans in order to collect revenue from other Catholic followers.[12]

Bibliography

- Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance State: the Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy.” In the Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge

- Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Theunissen, Hans. Ottoman-Venetian Diplomatics: The Ahd-names. 1998.

See also

- Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

- Capitulation (treaty)

- Economic history of the Ottoman Empire

- Foreign relations of the Ottoman Empire

- Conclave capitulation

- Achtiname of Muhammad

External links

References

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance State: the Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy.” in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge (Page 63). .(Page 64).

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002 (Page 187).

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.(Page 187).

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.(Page 193).

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance State: the Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy.” in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge (Page 63).

- ^ Theunissen, Hans. Ottoman-Venetian Diplomatics: The Ahd-names. 1998. (Page 1-3).

- ^ Theunissen, Hans. Ottoman-Venetian Diplomatics: The Ahd-names. 1998. (Page 249).

- ^ a b c Theunissen, Hans. Ottoman-Venetian Diplomatics: The Ahd-names. 1998. (Page 188).

- ^ Theunissen, Hans. Ottoman-Venetian Diplomatics: The Ahd-names. 1998. (Page 188-189).

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance State: the Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy.” in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge (Page 64).

- ^ Theunissen, Hans. Ottoman-Venetian Diplomatics: The Ahd-names. 1998. (Page 191).

- ^ Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance State: the Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy.” in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge (Page 64-65).